the view from Adyar

Originally printed in the March - April 2003 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Burnier, Radha. "Delight as a Form of Yoga." Quest 91.2 (MARCH - APRIL 2003):68-69

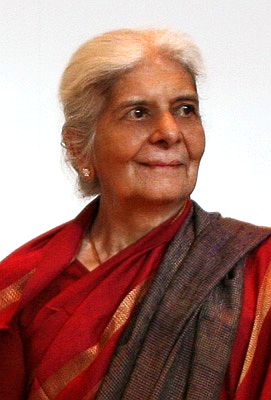

By Radha Burnier

DELIGHT IS THE ONE TRUE SOURCE OF ACTION. This statement by St. Augustine has been worded some what differently by other teachers. Some have said "Love and do what you will." Delight is intrinsic to love. To be with what one loves, to give to or receive from a loved person is delight. Action that expresses delight or love is not action based on an idea but rather is the manifestation of a state of being. We all know that people who are unhappy, frustrated, or insecure act awkwardly and create problems. One may, of course, respond that even those who are cheerful make problems, but they do so because their cheerfulness is not real; it is tainted by self-centeredness. The mind that is not self-preoccupied is serene and undisturbed, and it sheds gladness on others.

DELIGHT IS THE ONE TRUE SOURCE OF ACTION. This statement by St. Augustine has been worded some what differently by other teachers. Some have said "Love and do what you will." Delight is intrinsic to love. To be with what one loves, to give to or receive from a loved person is delight. Action that expresses delight or love is not action based on an idea but rather is the manifestation of a state of being. We all know that people who are unhappy, frustrated, or insecure act awkwardly and create problems. One may, of course, respond that even those who are cheerful make problems, but they do so because their cheerfulness is not real; it is tainted by self-centeredness. The mind that is not self-preoccupied is serene and undisturbed, and it sheds gladness on others.

Pain—physical or psychological—does not make anyone feel well. The feeling that there is something wrong when there is pain is universal. Why is that so? Why do we take it that everything is right when the mind is contented and happy? No logic or reasoning or answer is needed, because the fact is self-evident.

Pure joy and delight are the nature of the Self when it is undistorted. Because delight is the nature of our being, not only our true being, but the unalloyed, unspoiled state of being anywhere, we too are glad when we come into contact with it. A child plays, a bird sings, a little boy shouts with joy, and we too are happy.

Krishnamurti, translating Nature's delights into words, fills the hearts of the reader with rapture:

The stream, joined by other little streams, meandered through the valley noisily, and the chatter was never the same. It had its own moods but never unpleasant, never a dark mood. The little ones had a sharper note, there were more boulders and rocks; they had quiet pools in the shade, shallow with dancing shadows and at night they had quite a different tone, soft, gentle and hesitant. . . . the bigger stream had a deep quiet tone, more dignified, wider and swifter. . . . One could watch them by the hour and listen to their endless chatter; they were very gay and full of fun, even the bigger one, though it had to maintain a certain dignity. They were of the mountains, from dizzy heights nearer the heavens and so purer and nobler; they were not snobs but they maintained their way and they were rather distant and chilly. In the dark of the night they had a song of their own, when few were listening. It was a song of many songs.

The seventeenth century mystic Thomas Traherne describes the exaltation of letting go of the self:

You never enjoy the world aright till the sea itself floweth in your veins, till you are clothed with the heavens, and crowned with the stars; and perceive yourself to be the sole heir of the world, and more than so, because men are in it who are every one sole heirs as well as you. Till you can sing and rejoice and delight in God, as misers do in gold, and kings in scepters, you never enjoy the world.

Our real nature is ananda, "delight." Why then do we persistently renounce our birthright? Contentment is so rare. A constant and deep contentment is said to be the mark of the Yogi. True Yogis do not seek anything or want anything. Abandoning all the desires of the heart, they are satisfied in the Self by the Self (Bhagavad Gita 2.55). They are happy whatever happens; wherever they are. Why are not we so? Is it not strange that we seek a special technique to be ourselves, to know the absolute felicity of just being what we are. The name sadananda, "being-delight," is beautiful, for it points out that to be is to be full of delight—unbroken delight—and that is right and good.

Maybe one can change from restlessness and discontentment to deep unspoiled delight very quickly, almost overnight if we are serious about it. We can try it just for a while. Put aside even for a short time the thought of being in want, lacking this and that, having less or more in comparison to others. Just be! Not be something: I have done this and failed in that; I have not gone far or I have achieved. Let every picture be put aside, the idea of needing, as well as of having achieved. This is meditation. When the thought of oneself as being in want of anything, physical or spiritual dies, the mind is free, bright, and calm. That serenity is delight, a grace that is pine. That state of grace is called prasada in the Bhagavad Gita (2.64-5).

One can start by being aware with the heart, not as a mental idea, of the brightness and beauty of life. There is a happy aspect to everything. After getting bruised by a fall, instead of complaining and annoying others by self-pity, one can be happy that a bone is not broken. In At the Feet of the Master, which speaks of cheerfulness as a qualification, we are told, "However hard it is, be thankful that it is not worse." Let us learn to part with things gladly; the good side of parting is that it loosens the mind's hold on transient objects and makes one aware of the illusion of possession.

"All the world is a stage." The world drama goes on, changing between tragic and comic, with scenes of beauty as well as of horror. The spectator sees many disguises that the producer has fashioned. Whether the scene is sad or cheerful, the total effect is to delight the viewer, but the viewer must be detached to see through the disguises and the roles, and to hear the tale with the message of the master producer.

Mystics say that all creatures on earth joyously hymn the glory of life. Each creature is manifesting inits own unique way the marvelous content of the universal mind. Human beings are unable to do this spontaneously because we think of ourselves as independent of the source of all life. Therefore we miss the hymn of life.

When we train ourselves to see the bright and the good and take delight in the drama, even though the villain has faults, when we no longer want what is not there, we will become happy people and make others happy. But the happiness must be real, born out of a mind that has ceased to want. Delight is the state of not wanting, the beatitude of being, but not being somebody. It is the Yoga of learning to be simple, natural, and in tune with every bit of life.

Radha Burnier is the international President of the Theosophical Society. As a young woman she was an exponent of classical Indian dance and as such was featured in the film The River, by Jean Renoir. This column is a summary of a lecture she delivered at Adyar on December 30, 1996.