Printed in the Fall 2025 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama, "Inner Guru, Outer Guru, Secret Guru" Quest 113:4, pg 10-14

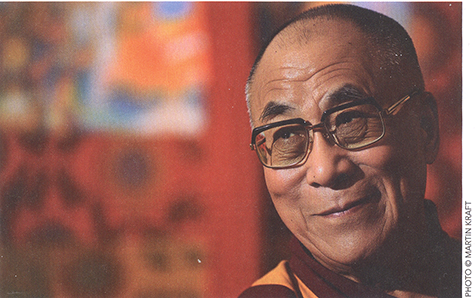

By Tenzin Gyatso, the Fourteenth Dalai Lama

This interview appeared in the first issue of The Quest, autumn 1988. It was held at the close of annual teachings and initiations in Bodhgaya, India, the place most sacred to Buddhists. It is selected from a book, The Bodhgaya Interviews, edited by Jose Ignacio Cabezón.

His Holiness: At the outset, I would like to express my greetings. I am not staying many days in Bodhgaya, so I have been very busy. At the same time there are many people this year, aren’t there? There is a much bigger gathering this year than last year.

His Holiness: At the outset, I would like to express my greetings. I am not staying many days in Bodhgaya, so I have been very busy. At the same time there are many people this year, aren’t there? There is a much bigger gathering this year than last year.

Now the teachings are finished and everyone is departing. Except for our memory, soon there will be nothing left of our days in Bodhgaya. This is the way of human life—time passes. As a Buddhist, one must think not only in terms of this lifetime, but in terms of trillions and trillions of years. To think in this way is also a form of practice. I think this is very important.

At the beginning, we must certainly learn from a teacher or from books. Then it is necessary to apply what we have learned to the new experiences and events we encounter in our daily lives. Now, in the present case, if we consider our departure from Bodhgaya, some people may feel sad. To dwell on this and to think, “Now we are leaving and we shall not see each other any longer” is not a very useful thing to do.

If, however, we contemplate the deeper significance, the implicit lesson in impermanence and change, and the nature of human life, then the experience of departing can be a useful one. It becomes meaningful. Physically we may be departing, but mentally, our memory and certain things we may have experienced in Bodhgaya—these will remain in our minds. The physical part cannot remain with you always. It will remain for a while and then depart. So, you see, all external material things, no matter how important or how beautiful, will eventually depart. But certain things which are related mainly to consciousness, to the inner experience, these, generally speaking, remain always with you.

Question: Your Holiness, how can we separate the essence of Buddhism from Tibetan cultural adaptations?

His Holiness: I think the basic teachings such as the Four Noble Truths and the Two Truths (conventional and ultimate) are the very foundation of Buddhism. These are teachings that are to be found in Indian Buddhism, Japanese Buddhism, Chinese, Thai, Burmese, and also in Tibetan Buddhism. They all have teachings such as the Four Noble Truths—these are basic to all forms of Buddhism. Now the Tantras are not practiced in common. They are practiced only in Tibet, in Japan, and perhaps in Korea. But we can nonetheless consider the Tantric teachings as authentic Buddhism, as the true teachings.

When we perform certain kinds of prayers and rituals in Tibetan Buddhism, in certain minor aspects, there may be Tibetan adaptations. These parts, then, can be dispensed with in the transmission of Buddhism to other cultures. For example, when we perform certain pujas (offering rituals), we use certain musical instruments. We use, for example, the conch shell: this is something we took from India. (In Tibet, there were no conches. But other instruments were common in Tibet.) When you Westerners perform these pujas, these rituals, it is not necessary for you to use these same instruments, you can use your own.

This is just one example of aspects that are local adaptations. In another place with a different culture and different people these things may not be relevant, they may not actually be useful, and that part should change. In the West, for example, there exists the tradition of using song; some Christians, for example, use song as a means of conveying and appreciating spiritual meaning. This is fine: it is useful.

Question: In the teachings there are many things mentioned that are contradicted by Western science. For example, it is claimed that the moon is 100 miles above the earth, etc. Many of our teachers hold these views to be literally true and Westem science to be wrong. Would Your Holiness comment on how we should view these teachings of the Buddha, and on how we should regard our teachers who hold to them literally?

His Holiness: This is a complicated matter. But I believe, and I have expressed this on several occasions, that basically a Buddhist attitude on any subject must be one that accords with the facts. If, upon investigation, you find that there is reason and proof for a point, then you should accept it. That is not to say that there are certain points that are beyond the human powers of deductive reasoning—that is a different matter. But things such as the size or position of the moon and stars, etc., are things that the human mind can come to know. On these matters it is important to accept the facts, the real situation, whatever that may be.

When we investigate certain measurements and descriptions as they exist in our own texts, we find that they do not correspond to reality. In such a case we must accept the reality, and not the literal scriptural explanation. This should be the basic attitude.

If something is contradictory to reasoning, or if it is found to be false after investigation, then that point cannot be accepted. That is the rule, that is the general attitude. For example, if something is directly experienced by the senses, then there is no question, no doubt, that we should accept it.

In the scriptures there are many different cosmological theories expounded. We do believe that there are many billions and billions of worlds, in the same way that Western science accepts there are limitless numbers of galaxies. This is something that is mentioned very clearly in scripture, though the size and shape may not be the same. They may be different.

For example, Mount Meru is mentioned in the scriptures. It is claimed to be the center of the earth. But if it is there, by following the description in scripture of its location, it must be found. At least we must get some indication that it is there, but there is none. So we must take a different interpretation from the literal one.

If there are teachers who still hold to the literal meaning, then that is their own business. There is no need to argue with them. You can see things according to your own interpretation, and they can see things as they see fit.

In any case, these are basically minor matters, aren’t they? The foundation of the teachings: the Four Noble Truths, what they have to say about the nature of life, about the nature of suffering, about the nature of mind—these are basic teachings, these are what is most important, what is relevant to our lives. Whether the world is square or round does not matter as long as it remains a peaceful and good place.

Question: Can Your Holiness comment on the power of a holy place such as Bodhgaya? What makes virtuous activities performed here more powerful and worthy of more merit?

His Holiness: The fact that many holy beings, spiritually advanced practitioners, stay and practice in a certain place makes the atmosphere or environment of that place change. The place gets some imprint from the person.

Then when another person who does not have much experience or spiritual development comes and remains in that place and practices, he/she can obtain certain special kinds of experience, though of course the right type of motivation and certain karmic forces must also be present in the person as contributing factors for such an experience to come about.

According to the Tantric teachings, at important places there are nonhuman beings, like dakinis, who have bodies that are much more subtle than those of humans. When great spiritual practitioners stay in a certain place and perform meditation and rituals there, then that place becomes familiar to beings like dakas and dakinis, so that they may inhabit the place and travel around it. As indications of this, sometimes one may notice an unusual noise or smell that seems to have no particular reason for existing. These are indications that some higher beings, different beings who have more experience, are inhabiting or traveling through that place. This could also act as a factor influencing whether or not a place is considered special.

In addition, in regard to Bodhgaya, we know that the Buddha himself must have chosen this place for a particular reason—this we believe. Due to the power of his prayer, later, when his followers actually come to this place, they may feel something—hence the power of the Buddha’s prayer could also be a factor.

Perhaps we must take human psychological factors into account as well. For example, Mahayana Buddhists feel strongly toward Sakyamuni Buddha, toward Nagarjuna, etc. In my own case, I have a strong feeling towards the Buddha, towards Nagarjuna, Arya Asanga, to all of these great beings. So when you stay at the place where these people were born and remained, then you feel something. If you use this feeling in the right way, that is fine, there is nothing wrong with it.

Question: Could Your Holiness say something about growing open to one’s own inner guru and also something about the absolute guru?

His Holiness: In general, there is said to be an inner guru, an outer guru, and a secret guru. This is explained in different scriptures, and there are some slight differences in the way these concepts are interpreted or explained in Nyingma, Kargyu, Sakya, and Gelug (the four main orders of Tibetan Buddhism). Likewise, there are differences in the way the different sects explain the four types of mandalas. Outer, inner, secret, and the mandala of reality (de kho na nyid).

The internal or inner guru is the innermost subtle consciousness of the guru. Now that innermost subtle consciousness which your guru has is exactly similar to the innermost subtle consciousness you yourself have. What then is the difference between the two? The guru, who is in effect using this subtle consciousness in his practice, is actually experiencing it with awareness, so that the consciousness becomes a form of wisdom.

When we faint or when we are dying, we too experience that subtle consciousness. And although that consciousness is there, although it is present, we are not aware or conscious of it. We do not realize that it is present. So the real guru, the inner guru, is this consciousness that exists within ourselves. It is also the inner protector, the real ultimate refuge. It is the experience of that state that is the real teacher, that is the real protector, that is the real Dharma. Thus there is this inner guru.

Now, you see, the manifestation of that consciousness in the form of a human body we call the external guru.

As for the secret guru, it is the special method or way that brings us to an awareness of that consciousness. This includes breathing meditations, the generation of bliss, and of the inner heat. These we may call the secret guru because it is through these techniques that we come to realize the inner guru. Sometimes this subtle consciousness is called “inner guru,” sometimes it is called the “ultimate guru.” In any case the two terms are synonymous.

According to the sutras, according to the Madhyamika school, “the absolute” refers to sunyata, to emptiness. In the Mahanuttaniyoga Tantras, however, the word “absolute” has two meanings. It can refer either to sunyata itself or to this special type of subtle consciousness (not to the ordinary, vulgar levels of mind, however). For the most part, when these scriptures refer to “the ultimate,” they are referring to the consciousness aspect, but not to ordinary consciousness, to a consciousness we call rigpa, the ultimate, innermost subtle consciousness. Even when the five senses are not active, the subtle consciousness is still there, though it is overpowered by the senses.

You see, all the senses are individual types of consciousness. The eye consciousness has color, shape, and so forth as its object: the ear consciousness perceives sounds, etc. Even though they are all different, having different objects, nonetheless, they are all of the same nature, of the nature of knowing. They may come to know through different means, but they are still of the nature of knowing. This common aspect they have in common we call shes pa, knowing. Now the rigpa, which we can call “awareness,” this innermost subtle consciousness, is also of the nature of “knowing.” It too is a “knower,” just as the eye consciousness is a “knower.” So both the coarser sense consciousnesses and the more subtle rigpa are of the nature of knowing. They are both “knowers.” The coarser types of consciousness come to know something because of the subtle consciousness. The basic nature of knowing thus comes from, or is due to, the existence of the subtle consciousness. Even during moments when the sense organs are very active, if we rely on the instructions of a proper, experienced teacher, we can separate the two experiences: the path of the coarser consciousnesses from the path of the subtle consciousness.

These points, however, are difficult. First of all, the matter being discussed is difficult; add to that the fact that the Dalai Lama’s English is poor, and it makes for an altogether awkward situation. You see, it is actually quite shameful. For quite a few years now I have had to speak with my own English, but it never comes out properly. In fact, sometimes, instead of getting better, it actually declines!

Question: Your Holiness, in what way does an individual consciousness exist? What part of that consciousness is still present after death? And is there a total dissolution of that consciousness when one reaches Buddhahood?

His Holiness: Consciousness will always be present, though a particular consciousness may cease. For example, the particular tactile consciousness that is present within this human body will cease when the body comes to an end. Likewise, consciousnesses that are influenced by ignorance, by anger, or by attachment—these too will cease. Furthermore, all of the coarser levels of consciousness will cease. But the basic, ultimate, innermost subtle consciousness will always remain. It had no beginning, and it will have no end. That consciousness will remain. When we reach Buddhahood, that consciousness becomes enlightened allknowing. Still, the consciousness will remain an individual thing. For example, the Buddha Sakyamuni’s consciousness and the Buddha Kasyapa’s consciousness are distinct individual things. This individuality of consciousness is not lost upon the attainment of Buddhahood. Still, all of the minds of all Buddhas have the same qualities—in this sense they are similar. They have the same qualities while still preserving their individuality.

Question: What does Your Holiness think of unilateral nuclear disarmament?

His Holiness: Now, you see, world peace through mental peace is an absolute. It is the ultimate goal. But as for the method, there are many factors that must be taken into consideration. Under a particular set of circumstances, a certain approach may be useful while under other circumstances, another method may be more useful. This is a very complicated issue which compels us to study the situation at a particular point of time. We must take into account the other side’s motivation, etc., so it is a very complex matter.

But we must always keep in mind that all of us want happiness. War, on the other hand, only brings suffering—that is very clear. Even if we are victorious, that victory means sacrificing many people. It means their suffering. Therefore, the important thing is peace. But how do we achieve peace? Is it done through hatred, through extreme competition, through anger? It is obvious that through these means it is impossible to achieve any form of lasting world peace. Hence the only alternative is to achieve world peace through mental peace, through peace of mind. World peace is achieved based only on a sense of brotherhood and sisterhood, on the basis of compassion. The clear, genuine realization of the oneness of all mankind is something important. It is something we definitely need. Wherever I go, I always express these views.

Question: Western monks and nuns sometimes find it difficult wearing robes in the West. We are often stared at and looked upon as being strange. Does your Holiness recommend wearing robes in non-Buddhist countries?

His Holiness: This we must judge according to particular cases and circumstances. If you can remain in robes without disturbing others, then of course it is better to wear robes. In some particular cases, however, this may be difficult.

Basically, as practitioners, we must remain in society. We must be good members of the society in which we live. So if society has a negative attitude towards you, this may be good neither for yourself nor for society. This is the basic position. Now if for this reason, one decides not to wear robes, if it is not suitable, better not to do so under those circumstances. This is all right. If the circumstances should change, then change. Gradually the society itself may change its attitudes. The West is a society in which Buddhism has never flourished, and this is changing. I think that, compared to thirty years ago, today when monks travel on an international air carrier, they are recognized as monks. So, you see, time goes on, and gradually things will change. The important thing is not what we wear but our behavior in our everyday lives.

Thank you very much. Today there is not much time, but I am happy to have shared these few moments with you. All of us have come from different parts of the world and we may even have different faiths, but we all have the same human mind. Isn’t that so? When it comes down to the level of basic human qualities we are the same, there are no differences. On a superficial level, however, there are many, many differences. So what we need to do is go to a deeper level. There we find that we are all human brothers and sisters. No barriers exist for us. Everyone wants happiness and does not want suffering, and everyone has the right to achieve permanent happiness. So we must share each other’s suffering and help each other. If we cannot help others, at least we must not harm them. That is the main principle. Whether we believe in the next life or not does not matter. Whether we believe in God or not doesn’t matter. But one thing that does matter very much is that we live peacefully, calmly, with a real sense of brotherhood and sisterhood. This is the way to achieve true world peace, or if not world peace, then at least a peaceful community. That is important, very useful, and very helpful. Thank you very much.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama is recognized as the fourteenth incarnation in the line of Dalai Lamas, and is the head of the Tibetan government-in-exile in Dharamsala, India. He is known the world over as a great spiritual teacher and tireless worker for peace.

Dalai Lama, excerpts from Answers: Discussions with Western Buddhists, edited by José Ignacio Cabezón. Copyright © 2001 by José Ignacio Cabezón. Reprinted by arrangement with The Permissions Company, LLC on behalf of Shambhala Publications Inc., Boulder, Colorado, www.shambhala.com.