Originally printed in the Winter 2012 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Tulku, Tarthang . "Making Mind the Matter." Quest 100. 1 (Winter 2012): 28-30, 40.

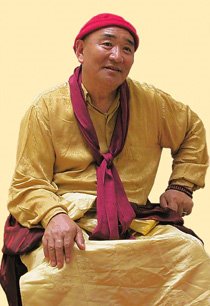

by Tarthang Tulku

As the members of our community go about their work, they try to keep the goal of understanding the teachings close to their hearts and minds. We are looking for ways to make the Dharma, the Buddha's teaching, relevant to our minds and to explore the activity of our minds in light of the Dharma.

As the members of our community go about their work, they try to keep the goal of understanding the teachings close to their hearts and minds. We are looking for ways to make the Dharma, the Buddha's teaching, relevant to our minds and to explore the activity of our minds in light of the Dharma.

Taking work as Dharma practice gives us the opportunity to investigate experience as it happens. What matters is learning to identify self and self-image in operation, always going on to ask another question instead of settling for a particular understanding. Here are some suggestions, based on my own observations, on ways to do this.

Examining the Senses. It may seem that our senses operate in a neutral way, but that is only because we have not learned to look closely. Just as science has learned to investigate in depth the atoms and molecules that make up matter, so we can learn to look at how we see and hear and feel and know. Rather than focusing on what appears to the senses, we can be aware of the activity of sensing, and of the way we react to what we sense.

There are many ways to conduct this inquiry. For instance, instead of focusing on objects, we can be aware of space as the background from which objects appear. Instead of accepting the way things are, we can determine how appearance develops through a series of transitions that unfold in time. Instead of accepting the identity of what is sensed, we can ask how our own reactions and sense of self-identity contribute to the feel and flavor of appearance.

The Changing River. Like a river, experience is never the same from one moment to the next, but we tend to ignore change and emphasize similarity. Insisting that the past has gone and the future has not yet come, we turn the present into something static: a fixed and rigid identity. To counter this tendency, we can focus in our experience on how things change from moment to moment. Right now I think I am the same person that I was last year or five minutes ago, but in fact the mind, feelings, and desires are constantly changing. Instead of insisting on sameness, can we simply appreciate the subtle differences?

We sometimes worry that we can't see the forest for the trees, but the opposite is also true: Once we have identified the forest, we find it hard to notice the twigs, the leaves, the branches, the birds, and the rustling underfoot. The Buddhist system known as Abhidharma offers the tools for analyzing subtle changes in the mind and learning to notice different levels of cognition and perception. Mantrayana teachings, which use the science of mantra to illuminate the path to enlightenment, and the samadhis, the body of knowledge that focuses on conduct, take this analysis to still more subtle levels. But daily experience can be a preparation for these more advanced approaches. Right now we can notice changes in experience and trace the consequences of such changes, and we can experiment with modifying or initiating changes on our own.

Beyond Samsaric (Delusory) Mind. Beginning meditators usually focus on calming the mind or simply observing experience. This is natural, since our thoughts and imagination give us so much trouble. But tending to mind and mental events the way a shepherd tends his sheep is inherently limiting. We may meditate in this way for years without a significant change in how mind operates. Ironically, the self that fixates on its mental projections knows little about how those projections arise and operate. When we always meditate in this way—in preventive mode—we cannot add to this store of knowledge.

Instead of staying focused on the content of illusion mind, we can investigate the body of mind. To really succeed at this means cultivating samadhi and prajña(transcendent awareness), but we can also conduct an initial and rewarding investigation in the midst of ordinary experience. All we need to do is learn to recognize our own projections and preconceptions in operation. Like a spider who gets caught in its own web, we are constantly getting trapped in structures that the mind sets up. If we can see this pattern in operation, we can become more aware of how the mind works, and this will make it easier to work with mind itself.

Multiple Experience. Whatever we experience, there is also the one who experiences and interprets. As we interpret, we are also offering a self-interpretation. Like our sensings, our interpretations go in two directions at once, and we can practice being aware of both at the same time.

We can also go further into the complications of mind. As mind projects outward, it is confirming preconceptions, adjusting its own role and activity, and assigning and refining meaning. In every moment of experience, it goes off in many directions, like a ray of light split into many colors by a prism. It is not easy to keep track of all this, but at least we can make a start. Sense experience is a good place to look, because it is so immediate. We can develop a sensitivity to the manifold directionality of experience that might otherwise be too complicated to observe.

Following Experience into Aliveness. Although investigating our own experience leads us into the realm of interpretation, it does not have to lead us away from the richness that experience holds. Interpretation is just another layer of experience, with its own aliveness. Similarly, minding, sensing, cognizing, and identifying are all richly alive, each in its own way. A sound is made and a meaning pronounced; self-image and identity emerge to name and define what has been experienced; the senses gather together to make more meanings. It is a mistake to think that all of this happens after experience has taken place. Instead, each of these steps is part of the living experience, available to inquiry.

If we let the aliveness of mind's interpretations and mindings guide us toward an understanding of how experience is identified and assigned significance, we can take a further step, noticing how mind's way of patterning repeats itself again and again. Different features appear, but the rhetoric of minding and sensing stays the same. Even in dreams, the rhythm of mind in operation is never once interrupted.

Staying with the Unknown. Like quicksilver, the mind is never at rest, and like quicksilver it slips away when we try to take hold of it or penetrate beneath its surface. Always sensing, always interpreting, mind goes its own way. It makes meaning even where there is no meaning. What resists being assigned meaning, what stays unknown, is dismissed as irrelevant and of no value.

One way to challenge these tendencies is to let the unknown stay unknown. At once certain aspects of experience become more accessible: balance and neutrality, being open, and allowing. Staying with the experience of not knowing allows us to ask questions that would otherwise be dismissed. For instance, does form arise from ignorance or from wisdom? The mind at once leaps in with an answer, but this is only at the level of stories. If we can let ourselves not know the answer, we can explore the question at a deeper level, asking within experience instead of taking a stand on experience. We can see how well we understand mind itself, and we can ask how mind relates to mind.

Intrinsic Certainty. As we go about minding our stories, what are we certain of? Can we investigate this question without depending on stories? Can we go to a depth of certainty deeper than any story, deeper than the conditions we set for understanding? These questions pose a challenge. As long as we rely on identification and interpretation we may not even be able to say what they mean. Still, once we discover a way to start looking, it does not matter where we head. Every direction leads us into the depth of mind.

Knowing Our Solidity. Beneath the particular story in effect right now, we rely on an identity that feels solid. We simply know we are one mind, one consciousness. If we can go to that level, where everything seems solid, the notions and assumptions we use to shape experience—our ordinary way of thinking—may look different. Even our ideas about awareness, mind, consciousness, and experience may present themselves differently, revealing other features of mind.

Caring Brings Understanding. To understand, we must care. When we care, we are not disturbed by the obstacles that arise on the path to understanding, and we easily overcome emotionality. The Dharma tells us that if we love and care for knowledge, then by taking the path of knowledge, we come to know how to love and care for ourselves. We take responsibility for what we can bring about in this life, and we set about eliminating confusion and other hindrances that prevent mind and self from functioning at their full potential.

This kind of caring does not depend on being ready to undertake serious study of the Dharma. It is enough to see that we are the cause of our own experience, for then we can look for ways to cultivate whatever is positive. If we make it our aim to contribute and to experience as fully as possible, we will inevitably realize that our own knowledge is not sufficient to guide us, and we will explore ways to improve it. If we feel some connection to the Dharma lineage, we may recognize that today there are fewer and fewer examples of individuals who manifest profound knowledge in their own lives. In our own small way, we may resolve to do what we can to become examples of knowledge and caring for our friends, through simple acts such as kind words and helping gestures.

Although it is hard to claim that we can manifest complete honesty and compassion toward ourselves and others, we can imitate the examples of those we admire and whose lives we study. Whether we call this working for the Dharma or working for ourselves, we live in a way that does not waste the opportunities we have been given. We shape our own karma.

Mind is always dealing with the matter at hand, the "stuff" out of which its stories are constructed. But mind matters more than the subject-matter of its stories. If we care about knowledge, we will see this, because real knowledge happens at a level different from the stories we tell. If we care about ourselves, we will tire of our suffering and realize through our inquiry that we could do it differently, that mind could wake up from the stories it tells and recognize them as fictions.

Mind is always asking, "What's the matter?" But if we let go of what matters to mind, if we let mind be what matters, we can release ourselves from the hold of what mind tells us matters most. In time, we may realize what is the matter with mind. If what matters to mind has never happened, the problems we take so seriously dissolve. The rules of the game display less gravity; the limits on the range of positions available to us fall away. We can tell the story of how mind manufactures reality, or the story of how we have arrived at realization. Either way, it doesn't matter.

Tarthang Tulku is a visionary Tibetan lama, born in Tibet and trained by the greatest teachers of the previous century. He has lived in the U.S. since 1969, learning how Westerners think and act and experimenting with ways to transmit the Buddha's teachings in a new world. He is the founder of the Tibetan Aid Project, the Nyingma Institute, the Odiyan Country Center, Dharma Publishing, and most recently the Mangalam Research Center for Buddhist Languages. His books include Time, Space, and Knowledge: A New Vision of Reality; Skillful Means: Gentle Ways to Successful Work; and Gesture of Balance: A Guide to Self-Healing and Meditation. This article is adapted from his book Milking the Painted Cow: The Creative Power of Mind and the Shape of Reality in Light of the Buddhist Tradition, copyright © 2005 by Dharma Publishing. Reprinted with permission.