Printed in the Winter 2019 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Samarel, Nelda, "Preparing for Death and After" Quest 107:1, pg 26-31

By Nelda Samarel

An ancient Mesopotamian tale, retold by W. Somerset Maugham, tells of a merchant in old Baghdad who sent his servant to the market to buy provisions. In a little while the servant returned, white and trembling, and said,

An ancient Mesopotamian tale, retold by W. Somerset Maugham, tells of a merchant in old Baghdad who sent his servant to the market to buy provisions. In a little while the servant returned, white and trembling, and said,

“Master, just now when I was in the marketplace I looked across the square and saw Death staring at me. Please lend me your horse so I may ride away to Samarra, where Death will not find me.”

The merchant lent him his horse, and the servant rode away as fast as the horse could gallop. Then the merchant went to the market and saw Death standing in the crowd. The merchant went over to Death and said, “Why did you frighten my servant when you saw him this morning?”

Death replied, “I am sorry and did not mean to frighten him. I was merely surprised to see him here in Baghdad, for I have an appointment with him tonight in Samarra.”

It is said that the only certain things are death and taxes; some seem to avoid taxes, but no one avoids death. Yet we know little about this inevitable transition and less about how to prepare for it. We pretend that it doesn’t exist. We have inherited a terrible attitude toward death; it is black, solemn. We fear death because of the myths and misconceptions about the after-death states.

Myth: Death is the end; nothing in us survives.

Fact: There is no death in the sense of ceasing to be, only transition or change in the focus of consciousness.

Myth: Death is a plunge into the unknown.

Fact: We can know what lies ahead.

Myth: Sinners go to hell forever.

Fact: It doesn’t make sense for those who have done one wrong or made one mistake to suffer for eternity.

These misunderstandings keep us from thinking about death. But we need to think about it and come to understand it at this moment so that we may adequately prepare for it.

Preparing for Death

The one aim of those who practice philosophy in the proper manner is to practice for dying and for death. —Plato, Phaedo

To enjoy a peaceful and eventless death, you must prepare for it. —Sri Aurobindo

Learn to die and thou shalt learn to live. —F.M.M. Comper, The Book of the Craft of Dying

If we are planning a trip to an unknown place, how would we go about it? Would we fly somewhere, get off the plane, and think, “Where should I go? Where should I sleep?” Would we wander around and wonder what the place is like? Or would we prepare for our trip?

If we assume that death is not the end of consciousness, but simply a change in the focus of consciousness, then planning for it is no different from planning any other trip. Being prepared, we will arrive on the other side with the courage, confidence, and ability to keep us from experiencing bewilderment, fear, and helplessness in a strange new place. Not only will this preparation result in a more pleasant after-death experience, but it will allow us to be a center of peace, extending assistance to others who may not be as well prepared, and will also speed our own onward progress.

In order to prepare for the after-death states, we first need to explore what is meant by the afterlife.

Where Do We Go from Here?

Death is not a negation of life, or the opposite of life; it is the opposite of birth, but, like birth, it is a part of life. There is a continuum from birth to death, and that continuum endures after death. Quantum theory supports the idea that matter never “dies,” but continues in another form. What is that form?

Many traditions have theories and beliefs about the after-death states that may assist one in accepting death. There is a great deal in the Theosophical literature about this subject. The view presented here is based on a synthesis of H.P. Blavatsky’s writings, the Mahatma Letters from the Masters Morya and Koot Hoomi, and the writings of second-generation Theosophists Annie Besant and C.W. Leadbeater. Some of the second-generation writing appears to contradict points in the initial writings of Blavatsky and the Masters, but we must keep in mind that the second-generation writing was presented thirty years later and had the benefit of decades of further clairvoyant research on the subject. Much of Besant’s and Leadbeater’s thought was corroborated by the later Theosophical clairvoyants Geoffrey Hodson and Dora Kunz.

Before considering what happens after we die, it is essential to be familiar with the septenary human constitution.

Diagram 1. The Seven Human Principles

|

1. |

Universal |

One Self, One Reality, eternal, boundless; the most subtle level, with the highest rate of vibration. All principles are aspects of the Universal. One cannot know the Universal except through its reflection in the spiritual consciousness. |

|

2. |

Spiritual consciousness |

In close union with mind; associated with wisdom, discrimination, intuition, or spiritual insight. |

|

3. |

Mind |

Associated with words, ideas. One principle, separating functionally at birth into two: Higher mind: linked with conception; beyond reason; turned inward, interwoven with the higher principle, spiritual consciousness; knows and is therefore beyond reason. Lower mind: linked with perception and reason; turned outward to objects of sense; interwoven with fourth principle, the desire body; functionally disintegrates between incarnations. If mind gravitates more toward the desire body, it is focused on the material, earthly plane; if it gravitates more toward spiritual consciousness, it is focused on higher or spiritual planes. |

|

4. |

Desire body (astral body) |

Emotional consciousness, the craving principle within us; desire not only for base physical or emotional gratification, but also for more refined gratifications; seat of the personal will After death, it remains, along with the higher principles for a time, depending on intensity of the feelings, emotions, and cravings: the greater the intensity of feelings, the longer the desire body remains. Eventually it fades away, but its influences remain with the three higher principles. |

|

5. |

Etheric double |

Pattern body; precedes physical nature and is the model or mold around which physical develops. At the death of the physical, it survives for a brief time near the corpse, or until cremation. |

|

6. |

Vital energy |

Vital spark, the animating principle. Death of the physical body occurs when the vital energy is withdrawn. |

|

7. |

Physical |

Physical nature, physical consciousness; the densest level, with the lowest rate of vibration; the vehicle of other principles during life. |

The Septenary Human Constitution

Man, know thyself; then thou shalt know the Universe and God. —Pythagoras

Humans have a sevenfold constitution, ranging from the physical, which is the densest form, with the slowest rate of vibration, to the Universal, the most subtle, with the highest rate of vibration. (See diagram 1.) These principles are not stacked on top of one another, but are interrelated, occupying the same space in differing degrees of density of matter and rapidity of vibration.

The lowest four principles (physical, vital, etheric, and the desire nature) are known as the lower quaternary, the impermanent or mortal part of our nature. The lower quaternary is that part of us that is unique to this life. The higher three principles (mind, spiritual consciousness, and the Universal), known as the upper triad, arethe immortal, eternal part of our nature. The upper triad is the permanent individuality, or the part of us that reincarnates and knows the underlying unity of all existence. It is often referred to as the inner Self.

The rays of the sun are many through refraction. But they have the same source. —Mahatma Gandhi

We may think of ourselves, then, as immortal beings (mind, spiritual consciousness, and the Universal) who use the mortal personality and body (physical, vital, etheric, and the desire nature) for one lifetime.

Mind, having lower and higher aspects, may be seen as the swing principle: if mind gravitates toward the next lower principle, the desire nature, life is focused on the material or earthly plane; if mind gravitates toward the next higher principle, spiritual consciousness, life is more focused on the spiritual.

Preparation Note

How do we want to focus our life, toward the material or the spiritual? We make this decision every day, every moment, using the mind, but it is reinforced by the desire nature, where the personal will resides. Use the personal will, moment after moment, to help prepare for the afterlife but, equally importantly, to determine the quality of this life.

The Laws of Periodicity and Continuity

Understanding the laws of periodicity and continuity will help us conceptualize the after-death states. H.P. Blavatsky writes in The Secret Doctrine:

The Law of Periodicity asserts that, throughout the universe there are periods of activity followed by periods of rest; for every period of activity there is a corresponding period of rest, followed by another period of activity and then rest. Alternations such as day and night, sleeping and waking, and ebb and flow are facts so common, so perfectly universal and without exception, that it is easy to comprehend that in it we see one of the absolutely fundamental laws of the universe.

According to the law of continuity, existence is continuous, consciousness endures, and physical death is not the end of consciousness. There is an alternation between activity, representing physical manifestation, and periods of rest, the absence of physical manifestation.

What Happens When We Die?

Death may be understood as a withdrawal of the higher principles from the physical body. In reality, this withdrawal takes place gradually and goes unnoticed until it becomes pronounced. For example, as signs of aging begin, the physical body slows, there is less vigor, and the vital organs don’t function perfectly. Old age, then, is not the cause of death; rather it is the playing out of cycles; it is also the need for withdrawal and rest and for assimilation of life on earth.

Death of the physical and of the vital energy occur almost at the same time. For a short time, the etheric double remains near the corpse, then follows the physical and vital energy in dissipating. With physical, vital, and etheric death, one avenue of expression, one instrument of the personality, the physical, is lost. After death, we are not away somewhere else, but are right here, at a different rate of vibration, which is not perceptible to most.

Most people are unconscious at the moment of death and remain in this sleeping state for some duration after making their transition, awaking in the next state of consciousness, kamaloka.

Kamaloka

Kamaloka is a Sanskrit term translated as place or location of desires. Again, this is not a different place, but a different state of consciousness. Mme. Blavatsky writes:

We accept consciousness after death, and say the real consciousness and the real freedom . . . begins only after physical death. . . . [The ego] is then no longer impeded by gross matter . . . it is free, it can perceive everything. . . . Can you see what is behind that door unless you are a clairvoyant? There (after death), is no impediment of matter and the soul sees everything.

In kamaloka, one is subject to very strong cravings, such as for eating, drinking, and sleeping, and to emotions, such as anger, hate, and love. Because these may be appeased only by the physical body, and there is no physical body in kamaloka, there is no way to appease these desires, resulting in unpleasant experiences of unfulfilled longing. The greater the intensity of emotions and cravings, the longer they remain. Experience in kamaloka, then, is directly related, in both length and quality, to the intensity of our emotions on earth.

Preparation Note

Can we appease all our desires while in our physical form, living on earth? If we are tired and desire sleep, are there times when we’re unable to do so? When we’re late and in a rush, are we ever unavoidably delayed by traffic? When we wish for more money, do we always have it? And, if we do have more, are we content or do we desire still more? The idea, then, as we are told in Light on the Path, is “kill out desire.”

After death, as on earth, we live in a world of our own making. Begin preparing for the after-death states by making our world, our reality better. Begin by reducing desires, negative thinking patterns, and selfishness.

When we are asleep, only our physical body is on the bed. We experience consciousness in the desire body, or astral body, during this time. Our experiences through our dreams may thus indicate what our life will be like in kamaloka.

Preparation Note

It is not so much the content of our dreams as the emotions they evoke that is of greatest importance. Negative emotions in the dream state may indicate a need to change aspects of our waking state to one that is more balanced, wholesome, and peaceful. Be aware of dreams and use them to make positive changes in life.

In kamaloka, we have dropped our physical body and live in our desire body, or astral body. This body begins to disintegrate immediately after death. It struggles to preserve itself by rearranging its astral matter into concentric circles, with the coarsest material outermost, like a protective shell, creating a greater resistance to disintegration. This is a natural tendency, like the physical body’s attempts to preserve itself when endangered. This coarsest astral matter represents the basest of our desires while living in the physical. Since like attracts like, the astral body attracts coarse material from its surroundings. The individual is surrounded by base thought-forms, such as jealousy, vengeance, or greed, creating an unpleasant experience.

Preparation Note

After death it is helpful to resist the rearrangement of the astral matter and maintaining the desire body as it was in physical life. This requires resisting any fear that may be present after death, preventing the rearrangement of matter and resulting in a more pleasant and shorter life in kamaloka. This may be accomplished only through the personal will, which must be developed during physical life. Develop the personal will now through regular meditative practice. I will meditate.

Eventually the outermost matter disintegrates. When the passion has for the most part played out, the remainder of the astral body disintegrates, and our time in kamaloka is done. The duration in kamaloka is directly related to the amount of passion remaining when we die.

Preparation Note

The idea is to purge ourselves of all earthly desires during life and to direct our energies toward unselfish spiritual aspiration. I will give up my desires. I will get my emotional house in order now.

As every life differs, no two after-death experiences are identical. There always are variations. Kamaloka, then, is different for every person. Intensely spiritual people may pass through it quickly and regain consciousness in devachan, the next after-death state.

After Kamaloka

When the astral body has disintegrated or dissolved, along with the lower mind, the higher three principles (Universal, spiritual consciousness, and higher mind), move on. Before the desire body and lower mind completely fade away, however, their remnants—thoughts, desires, and emotions—are saved to become the elements forming the personality of the next physical incarnation. So right now we are actually forming the attributes of our next incarnation.

Preparation Note

Give consideration to every thought, desire, and emotion as those will determine our personality in the next incarnation.

Following is a period of gestation, an intermediate period of preparation for entry into the next state.

Devachan

After kamaloka, the three higher principles enter the state of devachan (meaning place of the gods or place of happiness). Like kamaloka, devachan is not a place, but a state of consciousness. Going from one state to another only signifies a change in the focus of consciousness from one principle to another. For example, while our consciousness is focused in the physical body, only the physical world is perceived and we live in that world; when our consciousness is focused in the astral or desire body, only that world is perceived.

Nothing of a gross nature like selfishness, greed, or sorrow can manifest in devachan because the material of the desire body is too coarse for devachan’s rarified atmosphere. Therefore the experience in devachan is one of supreme bliss. Unselfish aspiration is the dominant characteristic determining our experience of devachan. This aspiration may be in the form of unselfish pursuit of spiritual knowledge, high philosophic or scientific thought, literary or artistic ability exercised for unselfish purposes, or service for the sake of service. The keynote, then, is unselfishness, or altruism.

Whether or not one has achieved one’s ideals during earth life, whatever one has longed for will blossom into fulfillment in the after-death states, and into the next incarnation. Kamaloka is the experience of unfulfilled lower passions and desires, while devachan provides for the fulfillment of spiritual yearnings during earth life. In the after-death period, nothing comes from outside ourselves, and we are limited only by our lofty aspirations while in physical incarnation.

Devachan is not a reward of earth life, but a result. That which a man longs for, he becomes. “For as he thinketh in his heart, so is he” (Proverbs 23:7).

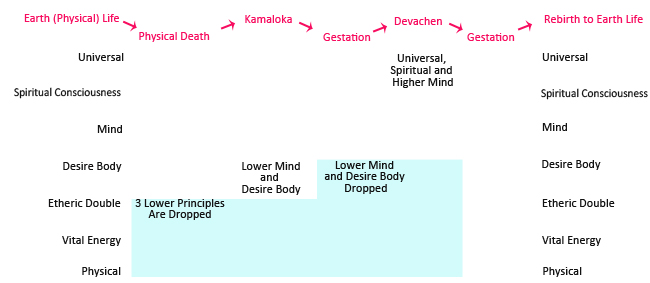

Diagram 2.The Seven Human Principles and the After-Death States

Preparation Note

The quality of our consciousness in physical life determines our after-death condition; our lives today are preparing us for our after-death states. To experience a better devachan, one must live a life of higher, spiritual aspiration. The cultivation of full consciousness and unselfish devotion during physical life not only benefits us and others now, but will produce results in the afterlife. As our consciousness grows, along with our altruistic motivation and service, we develop a greater power for good, which in turn results in more beneficial outcomes in both the physical world and in the after-death states.

Because only truth, beauty, and goodness may enter the devachanic state of consciousness, all coarse emotions and thoughts created by the personality while in physical incarnation are left behind, like checked baggage to be collected when one’s stay in devachan concludes. At that point, leaving devachan, we pick up our checked baggage, which becomes the blueprint for the personality of our next incarnation. Unlike the baggage we check with airlines, this baggage is never lost!

The spiritual experiences, the memory of all the good and noble from our previous incarnation, become immortal, surviving to our next incarnation. Past lives, then, never are wiped out, but blended into the life to be. We are a blending of all our past lives.

After Devachan

After devachan is another period of gestation, followed by rebirth (see diagram 2).

The mechanism of birth is the opposite of the mechanism of death. With birth we assume bodies, like robes, one by one; in death we cast off the robes. The Bhagavad Gita says, “As a man, casting off worn-out garments, taketh new ones, so the dweller in the body, casting off worn out bodies, entereth into others that are new.” Annie Besant writes in Death and After:

We are far more complex beings than we appear to physical sight. To one who knows this, death is an episode, not a tragedy. It is liberation from the physical body and not an annihilation of consciousness. For our consciousness is not in our physical body, though for a time it may be focused through it. Unchanged by death, the powers of our consciousness may be greater and the extent of our vision and perception somewhat larger because of our freedom from the physical limitation, but we are the same people after death as before, mentally, morally, and spiritually.

Dora Kunz taught that, in the last moments before physical death and immediately afterwards, the greatest gift we may bestow on ourselves is being at peace. Being at peace immediately prior to and during our transition has a profound effect on the afterlife and future incarnations.

Preparation Note

Because we cannot be what is foreign to us, especially during such a momentous time as this final transition, we must make peace a part of who we are at every moment. This means that we must begin our practice now, at this moment. Because we don’t know when our time will come, it is never too early to begin. Now is the time to meditate, as that is the only way to make peace a part of the fabric of our being.

How we live our lives determines our after-death states and our future lives. Through living a life of equanimity (nonattachment), peace, self-acceptance, self-knowledge, generosity (service for the good of all), morality, and patience, our lives today, in the afterlife, and in future incarnations will be of the highest.

Whether or not one has realized one’s ideals during physical life, whatever one has longed for will blossom into fulfillment in the after-death states, and in the next incarnation. The best preparation for death, then, is a well-lived life. Gain skill in living in order to master the art of dying.

Sources

Besant, Annie. Death and After. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1893.

———. Man and His Bodies. Wheaton, IL: Theosophical Publishing House, 1912.

The Bhagavad-Gita. Translated by Annie Besant. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1987.

Blavatsky, H.P. The Secret Doctrine. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1979.

———. Collected Writings. Fifteen volumes. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1991.

———. The Key to Theosophy: An Abridgement. Edited by Joy Mills. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1992.

———. The Secret Doctrine Commentaries: The Unpublished 1889 Instructions. Edited by Michael Gomes. The Hague, Netherlands: I.S.I.S. Foundation, 2010.

Chin, Vicente Hao, Jr., and A.T. Barker, eds. The Mahatma Letters to A.P. Sinnett in Chronological Sequence. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1998.

Collins, Mabel. Light on the Path. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1974.

Comper, Frances Margaret Mary, ed. The Book of the Craft of Dying and Other Early English Tracts Concerning Death. New York: Arno Press, 1977.

Gandhi, Mohandas. “Absolute Oneness.” Young India. Sept. 25, 1924; accessed Sept. 18, 2018; http://www.gandhimemorialcenter.org/quotes/2017/8/14/absolute-oneness.

Hodson, Geoffrey. Through the Gateway of Death. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1956.

Leadbeater, C.W. The Life after Death and How Theosophy Unveils It. London: Theosophical Publishing House, 1918.

———. The Devachanic Plane. Los Angeles: Theosophical Publishing House, 1919.

———. The Other Side of Death. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1928.

———. The Astral Plane. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1933.

———. The Inner Life. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1967.

Plato. The Dialogues of Plato. Translated by Benjamin Jowett. New York: Random House, 1937.

Samarel, Nelda. Helping the Dying: A Guide for Families and Friends Assisting Those in Transition. Quezon City, Philippines: Theosophical Order of Service, 2010.

Sri Aurobindo. Works of Sri Aurobindo. 37 vols. Auroville, India: Sri Aurobindo Ashram, 1997.

Nelda Samarel, Ed.D., longtime student of the Ageless Wisdom, has been director of the Krotona School of Theosophy and a director of the Theosophical Society in America. She has also served on the executive board of the Inter-American Theosophical Federation. A retired professor of nursing, Dr. Samarel has numerous publications and presents internationally. Her article “Meeting the Needs of the Dying” appeared in Quest, fall 2016.