Printed in the Summer 2022 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Hoeller, Stephan A., "Remembering an American Sage: An Admirer and Associate Reminisces about Manly Palmer Hall" Quest 110:3, pg 32-34

By Stephan A. Hoeller

The year was 1953. A recent arrival from war-torn Europe, I found myself transplanted to Southern California, where I was eager to make contact with a remarkable man who might have justly been regarded as the most notable expert on the esoteric tradition on the American continent, if not in the world.

Early in his life, he became known as the author of the folio-sized, beautifully bound, and illustrated volume entitled The Secret Teachings of All Ages (with a host of highly impressive subtitles). At the library and vault of the headquarters of the institution he founded, Los Angeles’ Philosophical Research Society, he held such treasures as first editions of H.P. Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine, replete with her handwritten notes, as well as alchemical and Rosicrucian codices, and a triangular cipher manuscript attributed to the Count of St. Germain. Having been introduced to these literary marvels by his kindly helper Mr. Gilbert Olson, I was eagerly looking forward to seeing the great man in person.

Early in his life, he became known as the author of the folio-sized, beautifully bound, and illustrated volume entitled The Secret Teachings of All Ages (with a host of highly impressive subtitles). At the library and vault of the headquarters of the institution he founded, Los Angeles’ Philosophical Research Society, he held such treasures as first editions of H.P. Blavatsky’s Secret Doctrine, replete with her handwritten notes, as well as alchemical and Rosicrucian codices, and a triangular cipher manuscript attributed to the Count of St. Germain. Having been introduced to these literary marvels by his kindly helper Mr. Gilbert Olson, I was eagerly looking forward to seeing the great man in person.

Some weeks later, I had the good fortune to attend one of Manly P. Hall’s weekday lectures in the smaller intimate lecture hall of the Society. I was filled with unprecedented amazement. This man was possibly the greatest orator of the twentieth century, and by that time had already delivered over 7,500 lectures and authored over 150 books and booklets. Yet he was available to us twice a week with his fabulous discourses, all perfectly structured and faultlessly delivered. From his youth until his passing, people wondered whether his phenomenal memory or his alleged occult powers were responsible for his oratory. (He always denied that he possessed paranormal faculties.)

From these early times on, I attended as many of his lectures as my schedule permitted. With the coming of the sixties, his audiences swelled to ever larger crowds. The sage met the burgeoning interest of the mostly youthful crowd with a t mixed reaction. On some occasions, he recalled that great cultural and even spiritual changes have at times come about as the result of the gatherings of young people. (He was fond of mentioning that the Meiji Restoration in Japanese history was virtually born in the teahouses of Tokyo and Kyoto.) At the same time, he viewed the undisciplined ways of the hippie subculture with disfavor. The occult interests of the sixties generation did not please him much. He considered ceremonial magic and witchcraft as unnecessary byways of the occult. Even more, he showed hostility toward visualizing and “manifesting” for material benefits. He considered using the occult and paranormal for material and selfish ends as bordering on black magic. Occultism without benevolent compassion appeared to him like sacrilege.

What then was Mr. Hall’s philosophy of life, or mystical orientation, that he communicated in his literary works and spoken words? To attempt an explanation, it might be best to refer once more to his magnum opus, the encyclopedic work devoted mainly to the Western esoteric tradition. Its subtitle reads: An Encyclopedic Outline of Masonic, Hermetic, Qabbalistic, and Rosicrucian Symbolic Philosophy. From these titles, we may deduce that he was aware of a tradition originally descending from the Mysteries of both early and late antiquity, namely Egypt, classical Greece, and Greco-Egyptian Alexandria.

Mr. Hall noted that his interpretation was of the “Secret Teachings concealed within the Rituals, Allegories and Mysteries of all ages.” His recognition of a secret tradition proceeding from these sources indicates some orientation that was not common in the late nineteenth or early twentieth century, except for the monumental contribution of H.P. Blavatsky and her followers.

Mr. Hall was reverential and enthusiastic about the person and writings of Blavatsky. (He even sculpted a fine bronze bust of Mme. Blavatsky, and he owned an almost life-sized copy of a painting of her by Heinrich Schmiechen, the original reposing in Adyar.) HPB, Mr. Hall believed, was the latest true representative of this tradition, which she enriched with elements of Buddhist and Hindu provenance. He recognized Blavatsky as the latest link in a mysterious chain of messenger-sages come to reenunciate the ageless message of authentic gnosis. In his work The Phoenix, he wrote, “Take away the contribution of H.P. Blavatsky and all modern occultism falls like a house of cards.” His most important contact with her tradition was the German-American Theosophist Max Heindel, author of The Rosicrucian Cosmo-Conception and other works, who, while identifying himself as a Rosicrucian, was teaching doctrines largely traceable to HPB.

Few know that Mr. Hall had served a sort of apprenticeship with Max Heindel early in the 1900s. In fact, he considered himself a “Rosicrucian Christian” and on other occasions described “the genuine Rosicrucian movement as an utterly reliable esoteric form of Christianity.” Mr. Hall also respected Annie Besant and called her “an esoterically inspired great social reformer and humanitarian.” One unconfirmed rumor declared that in the 1920s, Mr. Hall had an interview with Besant, offering his services if she thought he could function in the Theosophical Society. Dr. Besant reputedly advised him to continue his work on his own. Certainly he gave much evidence throughout his life of his sympathy for Theosophy and the Theosophical Society.

In his lectures and private conversations, Manly P. Hall frequently indicated that a certain convergence occurred on American soil, and that the two conjoining parties were a European transmission of ancient esoterica, originating in such sources as Neoplatonism, Hermeticism, and Gnosticism, and on the other hand, a certain psychic substratum of Native American provenance. In an essay published in 1964 entitled “Ancient America,” Mr. Hall indicated parallels and trajectories joining the spirit in these two esoteric streams. One of these, he felt, could be found in Native American tribal fraternities, the other in Hermetic, Rosicrucian, and Masonic secret societies from across the Atlantic. Far-fetched as such connections seem, their veracity is certainly worth considering. I am reminded of a motto presented to me as a dedication to some of Mr. Hall’s essays by their editor, the esoteric historian Mitch Horowitz: “Nothing is stranger than truth.” The quest for ecstasy, trance, dream, and vision, all of which periodically emerge in American culture, presented important contributions to occult America as well as to the general culture.

It may be useful at this point to take stock of Mr. Hall’s connection with some esoteric disciplines and teachings. By now, it may be apparent that he was truly a universal man and that his interest in various fields of esoterica was for the most part of an impartial nature. But it would be inaccurate to leave out of our considerations his great love for alchemy. In the vault of the Philosophical Research Society reposed numerous alchemical manuscripts that he had collected over several decades. It was considered one of the best collections of its kind on the American continent. Even C.G. Jung availed himself of Mr. Hall’s alchemical collection when writing his work Psychology and Alchemy.

The prize possession in Mr. Hall’s alchemical collection was a massive and colorful document called the Ripley Scroll, an actual parchment scroll of considerable magnitude, depicting in vivid colors and beautiful design the entire process of alchemical transformation. We were given to understand that only a small number of copies of this scroll were in existence. When requested to do so, Mr. Hall’s longtime librarian, Pearl Thomas, would bring out the Ripley Scroll from the vault and unroll it across several combined library tables, and we could view the entire transformation process to our delight.

Mr. Hall’s alchemical collection contained a considerable number of impressive codices in addition to the Ripley Scroll. Upon his demise, in tandem with one of my fellow lecturers, the late Roger Weir, we persuaded the heirs to sell the entire alchemical collection to the Getty Museum in Los Angeles, where now, after much restorative work, it is sometimes exhibited under the name of the Manly Hall Collection.

Though born in Canada (March 19, 1901), Mr. Hall spent most of his long life in the U.S. and in fact in Southern California. While in his twenties and thirties, he lectured all over the country in prestigious places, beginning with Carnegie Hall. Early in his life he was treated to a worldwide tour, which took him to much of Asia, the Middle East, and Europe. From his journey he wrote spirited accounts, often not without sharp criticism of the conditions he encountered on his journeys.

While still young, he became ill with an affliction of his thyroid (possibly cancer) in the course of which the ill organ was surgically removed. Chemical thyroid supplements being unavailable in those times, he was set up for a lifelong problem with obesity, the reason for which was not generally known. Nevertheless, having been raised by his grandmother, who was a physician of an alternative medical discipline, he enjoyed fairly robust health until the end of his life, and kept the Grim Reaper at bay for eighty-nine years until his death in 1990.

Like many outstanding intellectuals of his time, including Aldous Huxley and Christopher Isherwood, Mr. Hall once wrote for the movie studios, where he acquired a colorful coterie of acquaintances. One of his close friends was Bela Lugosi of Dracula fame, whose last marriage Mr. Hall solemnized in a ministerial capacity. Mr. Hall’s first wife, who suffered an early death, was a movie actress (his second wife, Marie Baur, was a student of esoteric matters). At the time I took up my residence in Hollywood, there were still numerous people at the movie studios who knew Manly Hall as “that tall interesting gentleman.”

The “Sage of Los Angeles” was a kindly and considerate gentleman, not only of the old school, but of the perennial school of civility. As it becomes increasingly evident, he was in friendly contact with numerous prominent figures in public life, the arts, and professions. I personally witnessed at least one visit of then Governor Ronald Reagan to Mr. Hall’s office, while his frequent telephone conversations with Elvis Presley were known to some of us. If walls could speak, the tales told by the neo-Aztec architecture of the Philosophical Research Society could disclose memories of visitors and admirers of great stature who walked there ever since its founding in 1934.

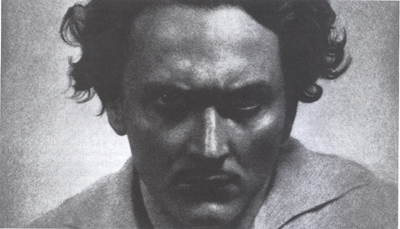

It is a teaching well known in some theologies (notably the Jewish) that the dead live on in the memories of those who knew them in life. As times pass and the admiring crowds vanish, it may be of importance for the few who were still present when the sage was with us to invoke their memories of this truly remarkable man. Those who remember will not let go of the image of the noble figure who was so often seen by us in his office or library and lecture room surrounded by splendid objects from many cultures, emanating an aura of gentlemanly refinement combined with subtle humor, seated in a huge chair, delivering long discourses of inspiring and informative content. When closing my eyes, I can still perceive the Barrymore-like profile and can hear the melodious voice conveying idealism, insight, and wonder. The memories of the sage have their own liberating power. In an age where fear, sorrow, and confusion are omnipresent, such thoughts are a great blessing indeed. Perhaps this small account of reminiscences may lighten the weight of time and place us on the eternal ways, where we might meet the unforgettable sage.

Stephan A. Hoeller was born and raised in Hungary and was educated for the monastic priesthood in his earlier years. A member of the Theosophical Society since 1952, he has lectured in the U.S. as well as in Europe, New Zealand, and Australia. He served as a professor of religion at the College of Oriental Studies for a number of years and is the author of four books published by Quest Books: The Fool’s Pilgrimage: Kabbalistic Meditations on the Tarot; Jung and the Lost Gospels: Insights into the Dead Sea Scrolls and the Nag Hammadi Library; The Gnostic Jung and the Seven Sermons to the Dead; and Gnosticism: New Light on the Ancient Tradition of Inner Knowing. He has been associated with the Besant Lodge of the TSA in Hollywood for many years and has been a bishop of the Gnostic Church (Ecclesia Gnostica) since 1967. He became the principal lecturer of the Philosophical Research Society (in addition to Mr. Hall) in 1970, and remained in that capacity for some years after Mr. Hall’s death.