Printed in the Winter 2024 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Long, Jeffery D "Service as a Spiritual Path: Swami Vivekananda’s Teaching of Karma Yoga" Quest 112:1, pg 23-29

By Jeffery D. Long

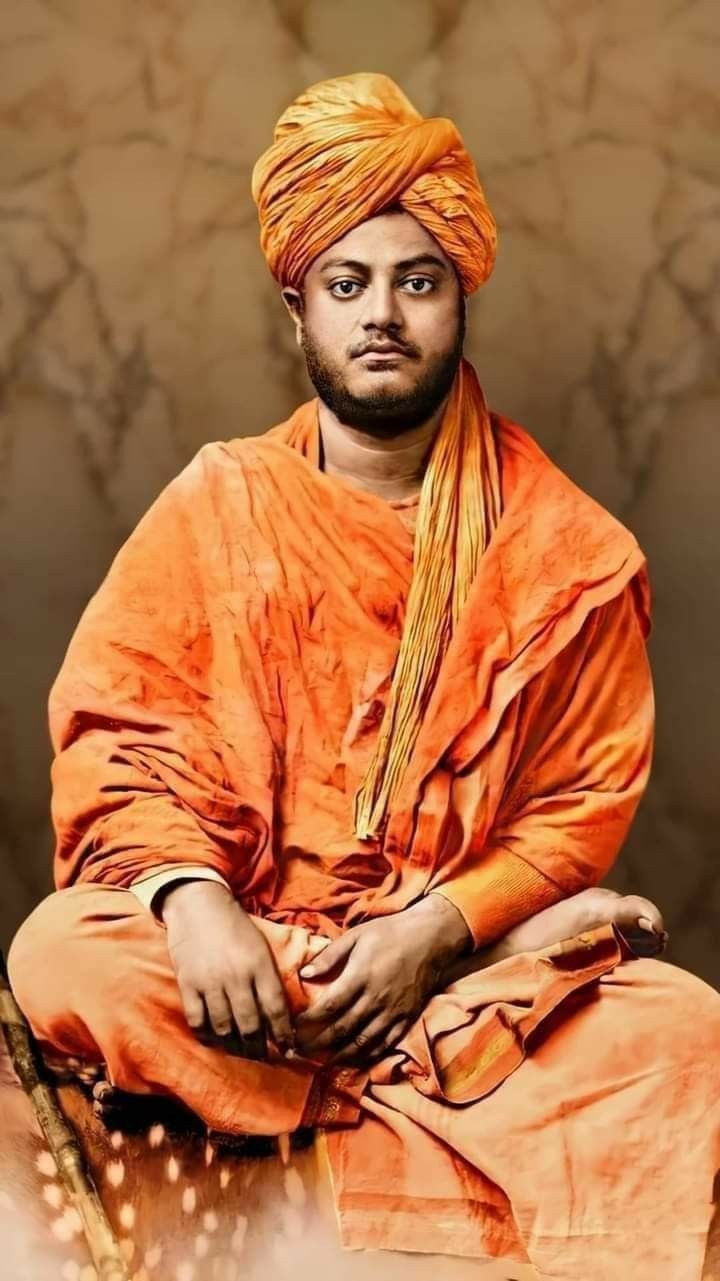

0The Indian sage Swami Vivekananda (1863‒1902) was one of the most influential figures in bringing the spiritual teachings of India to the modern West. In a lecture delivered in Boston on March 28, 1896, titled “The Spirit and Influence of Vedanta,” he says:

0The Indian sage Swami Vivekananda (1863‒1902) was one of the most influential figures in bringing the spiritual teachings of India to the modern West. In a lecture delivered in Boston on March 28, 1896, titled “The Spirit and Influence of Vedanta,” he says:

There has not been one religious inspiration, one manifestation of the divine in man, however great, but it has been the expression of [the] infinite oneness in human nature; and all that we call ethics and morality and doing good to others is also but the manifestation of this oneness. There are moments when every man feels that he is one with the universe, and he rushes forth to express it, whether he knows it or not. This expression of oneness is what we call love and sympathy, and it is the basis of all our ethics and morality. This is summed up in the Vedanta philosophy by the celebrated aphorism, Tat Tvam Asi, “Thou art That.”

The swami continues:

To every man, this is taught: Thou art one with this Universal Being, and, as such, every soul that exists is your soul; and every body that exists is your body; and in hurting anyone, you hurt yourself, in loving anyone, you love yourself. As soon as a current of hatred is thrown outside, whomsoever else it hurts, it also hurts yourself; and if love comes out from you, it is bound to come back to you. For I am the universe; this universe is my body. I am the Infinite, only I am not conscious of it now; but I am struggling to get this consciousness of the Infinite, and perfection will be reached when full consciousness of this Infinite comes. (Vivekananda, 1:399)

In 1897, Swami Vivekananda established the Ramakrishna Mission and coined its motto—atmano moksha artham jagaddhitaya cha: “For the liberation of the self and for the welfare of the world”—under the inspiration of his guru, Sri Ramakrishna Paramahamsa (1836‒86). Ramakrishna made two statements which Vivekananda would take as an imperative to the kind of social service to which he would later dedicate herculean efforts. These statements are Jatra jiv, tatra Shiv—“where there is a living being, there is Shiva”—and Jive doya noy, Shiv gyane jiv sheba: “not compassion to living beings, rather service to the living being that one knows to be Shiva.”

For Swami Vivekananda, and for the Ramakrishna tradition, the ideal of service cannot be separated from, and is indeed deeply rooted in, the understanding of oneness that is at the heart of Vedanta. Why should I serve others? Is such service not a distraction from the spiritual path? These questions fail to grasp the oneness, the nonduality, that underlies self and other. To posit duality between one’s own state of God-realization and the good of the world around us is to introduce a bifurcation that is ultimately a false one.

According to Swami Vivekananda, the practice of service to others as one would wish to be served oneself is a path to the full consciousness of the Infinite. The other that one is serving is, in fact, oneself. The servant and the one being served are not different, and both are divine. In practical terms, it certainly appears that there is a “self” helping an “other.” But in reality, the helper and helped are one, and the act of giving and receiving dissolves the duality which appears to separate them, joining them in a bond of love.

Love is essentially the experience of the deeper oneness of being. Love is what it feels like to be one with all existence. By helping the other, we in fact are helping ourselves, manifesting the love that is our true, fundamental nature. To again quote Swami Vivekananda: “Our duty to others means helping others, doing good to the world. Why should we do good to the world? Apparently to help the world, but really to help ourselves” (Vivekananda, 1:75).

Swami Vivekananda refers to the path of spiritual service as karma yoga. In this context, he is not referring to the law of karma, which is the principle of action and reaction. He speaks of karma in this latter sense as follows: “As soon as a current of hatred is thrown outside, whomsoever else it hurts, it also hurts yourself; and if love comes out from you, it is bound to come back to you.”

By contrast, karma yoga harks back to the meaning of the word’s original Sanskrit roots: action. This is the yoga, or spiritual discipline, in which action is performed with detachment from its fruits and offered lovingly as a form of service. This becomes a way to purify the mind of egotism and thus aid us on our way to the highest realization.

The philosophy of oneness underlying Swami Vivekananda’s ideal of social service not only helps to ground such service in a wider metaphysical worldview, it also serves as a theodicy: an account of why there is suffering in the world at all. Vivekananda unpacks these implications of karma yoga when he explains why we should help others in light of the insight that the world is itself a manifestation of the Self.

In the course of developing this theodicy, Vivekananda makes a number of claims that, if taken out of context, would sound like rejections of social service. But one must bear in mind the larger worldview behind these assertions. From the perspective of the Infinite, time, space, causation, and the seemingly fundamental distinction between subject and object are unreal. There is therefore, at the ultimate stage, no suffering, no servant, and no person in need of service. This is the paramartha satya, the ultimate truth. But if this is confused with an assertion of the vyavahara satya, or conventional truth of the realm of duality, it would sound cold, strange, and out of touch with the reality of the miseries of this world. If we bear in mind the extremely important distinction between these two aspects of truth, we can now turn to sayings that are seemingly at odds with Vivekananda’s deep commitment to the ideal of serving suffering beings.

“If we consider well,” Swami Vivekananda says, “we find that the world does not require our help at all. This world was not made that you or I should come up and help it. Is it not a blasphemy to say that the world needs our help? We cannot deny that there is much misery in it; to go out and help others is therefore the best thing we can do, although in the long run we shall find that helping others is only helping ourselves.” (Vivekananda, 1:75)

Most dramatically and counterintuitively of all, Swami Vivekananda tells us that the world “is perfect . . . We may be perfectly sure that it will go on beautifully well without us, and we need not bother our heads wishing to help it” (Vivekananda, 1:76).

Here Vivekananda is not denying that suffering is very real in the world that we are currently experiencing. As we have seen, he also says of the world that “we cannot deny that there is much misery in it; to go out and help others is therefore the best thing we can do.” But how can this be squared with the ultimate truth that the world is “perfect”?

The seeming imperfection of the world, as Vivekananda explains, can be likened to the exercise equipment in a gym: it is there so we can do the work that we need to do in order to realize our goal: “The world is a grand moral gymnasium wherein we have all to take exercise so as to become stronger and stronger spiritually” (Vivekananda, 1:80). Thinking that we will finally make the world a better place by solving all its problems is therefore futile, for it would defeat the whole purpose of these problems. In the words of Swami Atmarupananda, another teacher in the Ramakrishna tradition, “life is problem-solving.”

It is not the case, then, that we should not solve the problems before us. This is our dharma, our duty, as human beings, and a central theme of the Bhagavad Gita, in which the hero Arjuna is encouraged to do his duty, however difficult it may be, in the awareness that this is an essential part of his path to realization.

On the other hand, we should not solve problems on the assumption that all problems will one day be solved, or in the expectation that there will ever come a time when there will be such a thing as a problem-free existence upon the earth. Should that time come, the earth would cease to be a fitting place for living beings to work out their spiritual paths, for it would be missing an essential element of its purpose. If life is problem-solving, then a world without problems would be dead. Earth will be problem-free only when there are no more sentient beings upon it. From a spiritual perspective, the point is not so much solving the problems themselves (important though this is in the near term) as the transformative effects that our attempts to resolve them have upon us.

The world, therefore, is full of urgent problems, and it is imperative that we work to resolve them. But the world is also perfect, because problem-solving is precisely what we need to do to realize our ultimate oneness and manifest the love which is the infinite ground of our being. In a gym, we do not run the treadmill to get somewhere; we do not lift weights because the weights need to be moved from one place to another. These obstacles exist so that we can transform ourselves, and we choose to avail ourselves of them because we yearn for this transformation. In a gym, we are trying to cultivate physical health and fitness. In this world (in which we have chosen to be born), we are trying to realize the infinite potential that is the divine Self within us all.

To use another image, Swami Vivekananda says, “This world is like a dog’s curly tail” (Vivekananda, 1:79). We can try to straighten it out, but it is just going to flip back to its former position. We can and should solve specific problems by doing good in the world: specific conflicts can be resolved, specific wars prevented, diseases cured, and obstacles overcome. But life in samsara will always have problems; if it did not, it would be pointless. According to Swami Vivekananda, this way of thinking can help us to avoid fanaticism. In solving problems, it is important not to lose sight of the big picture:

It is a mistake to think that fanaticism can make for the progress of mankind. On the contrary, it is a retarding element creating hatred and anger, and causing people to fight each other, and making them unsympathetic. We think that whatever we do or possess is the best in the world, and what we do not do or possess is of no value. So, always remember the instance of the curly tail of the dog whenever you have a tendency to become a fanatic. (Vivekananda, 1:79)

Precisely how do problem-solving and service to others help us realize the infinite ground of our being? Karma yoga operates by subordinating the ego to something far greater than itself. It thereby brings the ego to such an attenuated state that it eventually vanishes altogether. Or rather, the ego becomes transparent, allowing the light of our potential divinity to shine through and thus be realized, actualized, and made manifest both in the world and in our consciousness. At this point we realize that we are not in fact the doers of action, but merely instruments of the Divine. According to the Bhagavad Gita, “one who is confused by egotism thinks, ‘I am the doer.’” (3:27; my translation). The ego makes us think we are the ones solving the world’s problems, and in extreme cases, that the world needs us to “save” it. This kind of thinking has caused much destruction in human history.

The aim of karma yoga is this purification of the mind from the stain of egotism:

The main effect of work done for others is to purify ourselves. By means of constant effort to do good to others we are trying to forget ourselves; this forgetfulness of the self [meaning the ego] is the one great lesson we have to learn in life . . . When a man has reached that state, he has attained to the perfection of Karma Yoga. This is the highest result of good works. (Vivekananda, 1:84, 86)

This is what is meant by “helping others is only helping ourselves.”

To further dramatize the point, Swami Vivekananda goes so far as to say that “unselfishness is God” (Vivekananda, 1:87). Unselfishness, for the karma yogi, is the highest ideal, just as the personal deity serves as the highest ideal for theistic devotees who surrender their egos to the Divine in the experience of loving devotion.

The ultimate purpose of karma yoga is to eradicate the ego. This fact has profound implications about the attitude with which one should engage in service. It prevents what both Swami Vivekananda and Sri Ramakrishna took to be the problematic attitude inherent in more conventional approaches to charity, which can all too often involve a self-congratulatory attitude or an attitude of superiority over those who are “less fortunate.” To again quote Swami Vivekananda: “It is a privilege to help others. Do not stand on a pedestal and take five cents in your hand and say, ‘Here, my poor man,’ but be grateful that the poor man is there so that by making a gift to him you are able to help yourself. It is not the receiver that is blessed, but it is the giver. Be grateful to the man you help, think of him as God” (Vivekananda, 1:76).

If the recipient of aid is not to be looked down upon in pity, but rather to be looked up to as divine, then aid is not charity but service, or seva, as it is known in the Hindu tradition. This is of course the point of Ramakrishna’s dictum: “not compassion [or pity: doya] to living beings, rather service to the living being that one knows to be Shiva.”

One could extend this idea even further and say that karma yoga in this sense is a form of bhakti yoga, the spiritual discipline of devotion: to cite another famous line of Swami Vivekananda, “work is worship” (Vivekananda, 5:245). Vivekananda famously exhorts his followers, in language almost reminiscent of the biblical prophets, to worship the living God in the form of suffering humanity—daridra narayana—even to the point of appearing to belittle more conventional forms of worship (Vivekananda, 7:245).

Vivekananda places the ethical implications of oneness at the front and center of his vision of Vedanta, going so far as to extol karma yoga, in the form of seva, as a path to liberation as valid as the other yogas of wisdom, devotion, and meditation. His ethical monism is the cornerstone of the Ramakrishna tradition’s ethos of selfless service. It is also deeply rooted in a traditional Vedantic understanding of oneness as expressed in the Bhagavad Gita: “I am not lost to the one who sees me everywhere and who sees all in me, nor is that one lost to me” (Bhagavad Gita 6:30; my translation).

Citing the Bhagavad Gita brings to mind the image of Lord Krishna, who is often represented as playing his flute. A modern bhakti poet, Radhey Shiam, writes eloquently of this flute as an image for the transformation of the ego that both karma yoga and bhakti yoga aim to cultivate. Shiam prays to Lord Krishna to make him like the flute, which must be hollow in order to allow air to pass through it. He prays that he may be empty of ego, empty of the sense of “I” and of being the doer of action, so that the Lord may use him to make beautiful music in the world. Through the practice of karma yoga, through selfless service that is offered with this understanding of oneness—that God is everywhere and in everyone—we become like Lord Krishna’s flute: instruments of divine action in the world. This is reminiscent of the first line of the Prayer of St. Francis from the Christian tradition: “Lord, make me an instrument of your peace.”

This is the essence of the philosophy of oneness propounded in the teachings of Swami Vivekananda and embodied in the service work of the Ramakrishna Mission. Service is not to be contrasted with the quest for realization and rejected as a distraction. Service in the spirit of oneness is realization. It makes the reality of oneness manifest in the life of the world through loving service aimed at serving suffering beings: service offered not in a patronizing spirit, but with love.

Sources

Bhagavad Gita. Edited and translated by Winthrop Sargeant. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2009. Translations in this article are taken from the Sanskrit text of this edition.

Swami Vivekananda. Complete Works¸volumes 1, 5, and 7. Mayavati, India: Advaita Ashrama, 1979.

Jeffery D. Long is professor of religion, philosophy, and Asian studies at Elizabethtown College in Elizabethtown, Pennsylvania, where he has been teaching since receiving his doctoral degree from the University of Chicago Divinity School in the year 2000. He is the author of a variety of books and articles, including Hinduism in America: A Convergence of Worlds and Jainism: An Introduction. He has spoken in many national and international venues, including three talks given at the United Nations.