Printed in the Summer 2018 issue of Quest magazine.

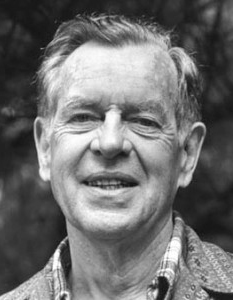

Citation: Grasse, Ray, "The Mythologist: Brief Encounters with Joseph Campbell" Quest 106:3, pg 26-29

Ray Grasse

A myth is somebody else’s religion.

The man on the car radio who uttered the above remark did so with a certain wry charm that caught my attention, not just for its wit but for its insight. He tossed it off in the most offhand of ways, yet it made a valid point about our blindness to our own belief systems.

The man on the car radio who uttered the above remark did so with a certain wry charm that caught my attention, not just for its wit but for its insight. He tossed it off in the most offhand of ways, yet it made a valid point about our blindness to our own belief systems.

It was nearly two years before I learned that voice belonged to Joseph Campbell, a scholar of mythology at Sarah Lawrence College. I had perused a few books and articles on mythology by that point, and I was always intrigued by the way mythological themes seemed to crop up in movies—like the time I heard director Robert Wise deliver a lecture and describe his surprise when someone pointed out the parallels between his film The Day the Earth Stood Still and the story of Jesus. Aside from experiences like those, mythology was never quite the burning passion for me that it was for some of my peers, who insisted it was one of those subjects all serious thinkers should be deeply versed in. As embarrassed as I was to admit it, those stories about long-forgotten gods and goddesses just left me cold.

That is, until I encountered Campbell. After reading just the first few pages of volume 1 of his Masks of God series, I was hooked. Writers like Mircea Eliade, Frithjof Schuon, and Claude Lévi-Stauss conveyed their ideas with a greater sense of seriousness, perhaps, but Campbell’s insights and style ignited a fire in me for the meaning and symbolism of those tales as no one else had. He conveyed such an infectious sense of wonderment that it felt like setting foot onto an exotic new continent with each new cultural mythology he mapped. Before long, I was driven to get my hands on everything he’d written.

The Campbell Seminars

In late 1981, I learned that Campbell passed through Chicago once every year to present lectures and seminars up on the city’s north side, and I jumped at the chance to attend them. The routine was much the same each time: he’d deliver a public lecture on a Friday night, followed by a seminar in greater depth on the same topic over the rest of the weekend. Since he was still relatively unknown in the Chicagoland area, the attendance at those weekend seminars was usually modest, with anywhere from fifteen to thirty people crowded together in a room on the Loyola University campus just off of Chicago’s lakefront. One year he’d discuss the work of James Joyce, the next year the psychology of the chakras, another year the Arthurian legends.

For a man in his late seventies, his vitality and enthusiasm were remarkable, as was his ability to rattle off volumes of information on a wide range of topics without ever relying on notes. Trying to digest it all sometimes felt like trying to drink from a firehose. Even his passing asides were provocative—intellectual depth charges that released their power only later on. Like his offhand remark that “Hitler set out to create the Third Reich but gave birth to the state of Israel instead.” Or “myth is the opening through which the transcendent truths of the universe pour into manifestation.” Of course, “Follow your bliss” was the one that eventually turned into a household meme, but it wound up being repeated so often that it began sounding more like fingernails on a chalkboard than the inspiration axiom he intended.

Then there were the anecdotes, a seemingly bottomless well of them. During one workshop he made passing reference to the fact that singer Bob Dylan “saved the Bollingen Foundation from going out of business.” The Bollingen Foundation was a publishing house and educational organization devoted to the works of Carl Jung. Campbell left the comment dangling for a few seconds before finally explaining that Bollingen had been on the brink of bankruptcy a couple of decades earlier, when Dylan unexpectedly remarked during an interview with Rolling Stone magazine how much he liked the I Ching—the traditional Chinese book of divination and wisdom. The most conspicuous translation of it on the shelves at the time was by Richard Wilhelm and Cary Baynes, published by Bollingen. Dylan’s passing comment was enough to catapult sales of the book, so that after teetering on the brink of bankruptcy, Bollingen suddenly found itself awash in money. That’s show biz.

But I discovered I didn’t quite see eye-to-eye with Campbell on everything. He clearly had no great love for popular culture and seemed to reserve a special distaste for the countercultural ’60s—the hippie movement in particular. Along with that, I sometimes detected a certain hard right-wing sensibility lurking beneath his comments that took me by surprise. But these instances were so infrequent, and his manner so charming, that it didn’t diminish my respect for his knowledge.

The Critique

Because of the small size of the groups, it was not only possible to ask questions during his talks but relatively easy to corner him during a break to speak with him privately. On one occasion I worked up the nerve to seek out his feedback on something I’d written just a few nights before, about Stanley Kubrick’s film 2001: A Space Odyssey. Since first seeing it as a teenager, I read everything I could about the film and was fascinated by the story’s symbolism, especially in the way it touched on classic archetypal themes. With those thoughts swirling in my head, I sat down and wrote a few paragraphs detailing my ideas about the film and how it symbolized the hero’s journey to enlightenment. It went like this:

The film’s central character, the astronaut Bowman, is shown journeying to the planet Jupiter—in traditional astrology, the planet most commonly associated with God. (In Sanskrit, by the way, the word for Jupiter is Guru.) But before he can complete this epic journey, Bowman must first slay the modern equivalent of the traditional “dragon”—a high-tech computer named HAL. Unlike the classic dragon, which is more of a symbol for the emotions and instincts, the computer represents a more modern challenge: the hyperrational mind. Bowman’s act of disengaging HAL speaks to the need to “unplug” the mind before one can reach enlightenment. Once that’s achieved, Bowman is able to enter the mysterious stargate—symbolizing transcendence itself. Once there, he undergoes a transformation and is reborn as a star child. At film’s end, he returns to Earth as an alienlike embryo, Bodhisattva-style, and is shown floating high above the earth. The mystic arc is complete, the hero now having returned to the world transformed by his experience.

There’s a hint of archetypal sexuality in all of this too, I added, since the large spaceship which housed Bowman for most of his journey is phallic-shaped, and upon arriving at his destination he’s ejected like a sperm cell and then plunged into the vaginalike “stargate” (depicted initially as two vertical walls)—after which a cosmic baby pops out, the aforementioned star child. Both Freud and Jung would have loved it, I felt sure.

I felt quite proud of my little commentary, and couldn’t wait to get Campbell’s feedback about it, never for a moment thinking how presumptuous it might be to expect that he’d find it terribly original. So during a break one afternoon, I handed him a copy, which he politely accepted. The next day during a break I was standing near him while he spoke with others, secretly hoping he might volunteer some feedback. When that didn’t happen, I edged closer, then nervously mustered up the nerve to ask him if he had a chance to look over my short piece.

“Excuse me, but did you have a chance to read my paper?”

“Oh, yes—I read it last night!”

He was upbeat, but there was no sign of judgment one way or the other. That was worrisome. I decided to go for broke and ask him outright what he thought. Obviously trying to be diplomatic, he said, “Well, you know . . . they based the movie on my work.”

What could I say to something like that? I might have been embarrassed or dejected, but he was so gracious about it that I simply said, “Oh!” Not only was my theory about the film nothing especially new to him, but the movie was inspired by his own research.

Well, maybe, maybe not. While I’m obliged to give Campbell the benefit of the doubt on that point, a colleague to whom I later mentioned this exchange questioned whether world-class geniuses like Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke really needed an outside thinker to come up with an archetypal story like theirs. It made me wonder whether Campbell’s suspicions about a direct connection between his work and that film might have been a bit like the motorist who buys a red Volkswagen and starts noticing every other red Volkswagen on the road. Perhaps the hero’s quest had been such a prominent a fixture in his own mind that when he saw it cropping up in a major Hollywood film, he assumed it was influenced by his own writings on the subject—whether that was really true or not. The irony is that Campbell himself taught that similar themes appear in places far removed from one another in time and space, and don’t necessarily require a causal connection. Did that happen here? We’ll probably never know for sure.

The Apparent Intentionality of Fate

Of all the ideas Campbell discussed in his talks, the one that left the greatest impact on me stemmed from a passing remark he made about the German philosopher Arthur Schopenhauer, specifically an essay he wrote titled “Transcendental Speculation on the Apparent Intentionality in the Fate of the Individual” (see sidebar). Schopenhauer suggested that when viewed through the lens of hindsight, one’s life can take on the appearance of a carefully constructed novel, as though the seemingly unintended events and accidents of one’s early life were really integral elements of a larger unfolding destiny. Campbell went on to quote the philosopher:

Would it not be an act of narrow-minded cowardice to maintain it would be impossible for the life paths of all mankind in their complex interrelationships to exhibit as much concert and harmony as a composer can bring into the any apparently disconnected and haphazardly turbulent voices of his symphony?

Who was this “composer,” I wondered? I found myself coming back to Schopenhauer’s passage repeatedly over the years, and would eventually incorporate it into my own writings about synchronicity and destiny. (Incidentally, I’ve been asked on occasion where one could find that translation Campbell drew those lines of Schopenhauer from. I asked Campbell about that myself, in fact, and he said it was his own translation.)

He mentioned those ideas of Schopenhauer’s during a weekend in which he explored the parallels between James Joyce’s Ulysses and Homer’s Odyssey. In addition to explaining how the symbolic stages in each of these works paralleled one another, Campbell also hinted at the richly interlocking worldview that Joyce portrayed in Ulysses. That perspective resonated beautifully with ideas I’d been trying to develop around the subject of synchronicity for the book I’d just begun writing, The Waking Dream. I was especially fascinated by Joyce’s manner of ingeniously interweaving disparate events as if they had been orchestrated by some great cosmic mind. I felt certain that must reveal something important about Joyce’s own view of life, so when I finally had the chance to question Campbell about that privately, I asked whether he believed Joyce’s two books Ulysses and Finnegans Wake truly reflected a symbolist and synchronistic vision of existence. He nodded cautiously, but was careful to clarify:

“Well, yes, that’s certainly true of Ulysses, but it’s not really true of Finnegans Wake.”

“How’s that?”

“Ulysses deals with the mythic aspect of our ‘day’ world, of waking life. But Finnegans Wake plunges you down fully to the world of dreams, into that deep mythic realm.”

After spending some more time with both of these difficult books, I eventually understood what Campbell meant. In Ulysses, the reader at least has some reference points to ordinary reality, but in Finnegans Wake the reader is cut loose entirely from worldly moorings and set adrift in the deep waters of the collective unconscious. It’s not so much a statement about our everyday world as about the cosmic ocean underlying it.

The Power of Myth

Campbell’s energy was such that when he died of cancer in 1986, it came as a surprise to everyone. As it turned out, it was finally in death that he attained the worldwide fame for which he seemed destined, thanks to Bill Moyers’ 1988 series of TV interviews called The Power of Myth. Among other things, it was from that show that viewers first learned that filmmaker George Lucas drew inspiration for Star Wars partly from Campbell’s work. And in contrast with Kubrick and Clarke’s script for 2001, George Lucas openly admitted to that influence, so there was no disputing matters this time around.

Though I didn’t continue to follow this subject as passionately as I originally did back then, my way of thinking continued to tap into mythic and archetypal currents in a number of key ways. That’s been especially true when looking at cultural trends and understanding how modern stories sometimes echo ancient themes. For example I’d find myself looking at Walt Disney’s animated film The Lion King and notice how it resonated with the Egyptian myth of Osiris, as well as Shakespeare’s Hamlet, with its story of a son avenging the evil uncle who murdered his father. Or I’d be watching Wim Wenders’s film Paris, Texas and notice how closely it resembled the ancient story of Odysseus, about a man struggling to find his way home in a semiamnesiac state, then meeting up with the woman he loved while he was in disguise.

I’ve also been fascinated by how our collective mythologies seem to be changing in both subtle and obvious ways, whether as found in novels, films, or even politics. Mythic undercurrents continue to pulsate beneath the surface of our lives. It reminds me of a metaphor penned by author William Irwin Thompson that I often come back to: we’re like a fly crawling across the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. Our personal stories are embedded in far larger dramas, but like that fly, we’re too close to recognize those stories spread out directly before us.

It’s left me wrestling with a question that first occurred to me decades ago, and which I still ponder from time to time: to what degree do our mythologies liberate us, and to what degree do they imprison us?

I’d love to have gotten Joseph Campbell’s answer to that one.

Ray Grasse is a writer, editor, and astrologer. He is the author of several books, including The Waking Dream (Quest Books, 1996), Signs of the Times (Hampton Roads, 2002), and Under a Sacred Sky (Wessex, 2015). He is also the former associate editor of Quest. He is a consulting astrologer, and his website is www.raygrasse.com.

All developments in the life of a human being would accordingly stand in two fundamentally different types of connections: first, in the objective, causal connection of the course of nature; second, in a subjective connection which exists only in relationship to the individual who experiences it and which is thus just as subjective as his own dreams, in which however, the succession and content are just as necessarily determined and in the same manner as the succession of scenes of a drama cast by a poet. That both types of connections exist simultaneously and the same occurrence, as a link in two quite different chains, which nevertheless have aligned perfectly in the consequence of which each time the fate of one matches the fate of another, and each is made the hero of his own drama while simultaneously figuring in an alien drama. This is freely also something that exceeds our powers of comprehension and can only be conceived as possible through the most fabulous preordained harmony.

—Arthur Schopenhauer

From Transscendente Spekulation über die anscheinende Absichtlichkeit im Schicksale des Einzelnen (“Transcendental Speculation on the Apparent Intentionality in the Fate of the Individual,” 1851) in E. Grisebach ed., Schopenhauers sämmtliche Schriften in fünf Bänden, “Schopenhauer’s Collected Works in Five Volumes”) vol. 4, 264–65 (Leipzig: Inselverlag, 1922), translated by Scott Horton. In Horton, “Schopenhauer: Causality and Synchronicity,” Harper’s website, Feb. 13, 2012: https://harpers.org/blog/2012/02/schopenhauer-causality-and-synchronicity/.