Originally printed in the July - August 2003 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Burnier, Radha. "The Urgency for a New Perspective." Quest 91.4 (JULY - AUGUST 2003):146-148.

the view from adyar

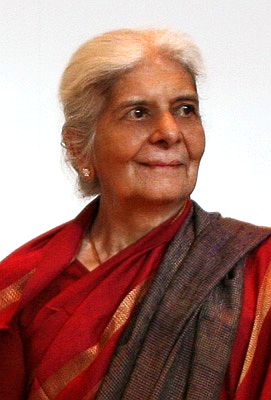

By Radha Burnier

"The world is too much with us," exclaimed the poet, and what people feel is the world is, indeed, very much with them. It hedges them in with the problems and the demands of everyday life, with changes that are unexpected and perhaps unpleasant. The difficulties begin in early childhood, possibly because parents are unsympathetic or because they do not know how to help their child. Later, the problems multiply—in school and college, in the course of a married life, with the additional pressures of practicing a profession or administering property. Life consists of meeting numerous responsibilities—the demands of a particular situation, the people with whom one becomes involved, the family and professional colleagues. Thus the world pushes each of us into involuntary actions.

"The world is too much with us," exclaimed the poet, and what people feel is the world is, indeed, very much with them. It hedges them in with the problems and the demands of everyday life, with changes that are unexpected and perhaps unpleasant. The difficulties begin in early childhood, possibly because parents are unsympathetic or because they do not know how to help their child. Later, the problems multiply—in school and college, in the course of a married life, with the additional pressures of practicing a profession or administering property. Life consists of meeting numerous responsibilities—the demands of a particular situation, the people with whom one becomes involved, the family and professional colleagues. Thus the world pushes each of us into involuntary actions.

We may be under the impression that we have a certain choice—in marriage, for example, in the friends we make, or in the interests we cultivate. But the "choice" is often quite illusory. Marriage may appear to be the result of free choice but, in fact, circumstances bring us into contact with a very limited number of people and our inner urges, coming into play in that particular context and circle, create a "choice" that is no real choice. We more or less "fall into the arms" of the situation; if we are intelligent enough we make the best of the situation.

In any case, from early childhood, outside conditions mold us into a pattern and provide us with values that we assimilate unconsciously. They are the source of the hidden impulses that result in action. In the East, one talks about the "bondage of karma." Karma is not an abstruse law at work in the universe or an abstract process. It manifests in our lives because we are overpowered by our environment and by the conditions around us. We are driven to involuntary actions and pursuits because, from our earliest years, we absorb, like a sponge, the ideas and values that are prevalent around us. These values are of many kinds and we are often unconscious of their implications. We may alter them a little but, nevertheless, we accept the conditioning. Our pursuits, which appear to be freely chosen, arise from the soil of these notions we have absorbed.

What people call "the world" comprises many attractions. There is the attraction of success, of money, of power, and of pleasure. They are like glittering lights in the distance, and our lives generally consist in making our way towards them. But they are like the will-o'-the-wisp, with only a seeming existence. They correspond to the pursuits in our minds, which are based on unconscious or partially conscious notions, ideas, and values. Desire projects the objects of desire and we imagine these to have a real existence. Because many people see them, they acquire an illusory reality; but it is only the desire that makes them into objects. For example, a woman, in herself, is not an object of desire; she is what she is. But someone else's desire for her makes her into such an object. What is attractive to one man may not be attractive to another. There is no object, no attraction per se because the nature of a thing as it is makes it stand independently.

This is pointed out in a well-known passage of the Upanishad, which states that a wife is not dear because she is the wife nor a husband because he is the husband; they are each non-relationally what they are. Each thing is what it is, but desire projects it into an object for itself. From this arises pursuit, and behind each pursuit there is a value-notion, which maybe religious, political, or personal. The personal value-notion is a thought we each have of ourselves, and from that there arises the many attractions that we see "outside" and that make the world into what it is for us. We take up postures in relation to people, to things, to ideas: thoughts arise in us, we form affiliations, we suffer antagonisms. All this complexity of likes and dislikes, of hopes and fears, takes birth in our consciousness from the soil of the values we have assimilated. So we each make our way through life, for the most part unconscious of what is going on within ourselves, not realizing what we are pursuing or why we are pursuing it, imagining that the world contains objects for us to chase, and thus projecting an image of the world that does not correspond to reality. So, for each of us there is a mirage-like world that arises from hidden sources within ourselves and that we take to be the world as it is.

The essence of worldliness lies in unawareness (avidya) of what is happening to oneself, in unawareness that the "world" is constructed by one's mind, that it has its source within oneself. Worldliness arises from not knowing that what is projected by the mind does not correspond to what is. If one were not blind, one would not be worldly. People who see—people of intelligence—realize that what is hidden within themselves prompts them to a variety of actions, attitudes, postures, affiliations, and rejections, all of which seem to be free but are not so in fact. Unawareness of what is happening within is not only absence of intelligence but of freedom, because it permits the "world" to push the individual into patterns of thought, into ways of action, into grooves, and routines.

Though the world is "too much with us" in one sense, in a different sense most of us totally ignore it. We are not "in the world" because we are unconscious and uncaring about what happens to it. There is widespread and appalling poverty. Millions are starving. There is tyranny in the major part of the world, suppressing human beings, making them conform out of fear, eroding their dignity, depriving them of the possibility of awakening that, which is deep and subtle, in the human consciousness. The free world is a very restricted area indeed. There is the unimaginable cruelty that humanity perpetrates on animals and on its fellow men and women. Torture is accepted as a part of state policy by nearly every country in the world. As anarchy increases, the tendency is towards suppression, towards the monolithic state. But all this, which is part of the world, is not in the consciousness of the majority except as an occasional piece of news. And news of happenings that are terrible and pitiable fades away after a week or two because, for the newspapers, they are no longer news, which means that the readers do not care what is happening.

Thus, the world goes on with each of us on an island of our own, enclosed in our own particular preoccupation—our family, our anxieties, and our ambitions. We ignore the rest of the world with its beauty and its tragedies.

The present-day world is one of tremendous political, economic, and social insecurity. There are many causes for this. The growing population leads to decreasing resources and increasing pressures. People demand more and more things and feel insecure as they see resources shrinking away. Insecurity only breeds fear, and this is visible everywhere in agitations, strikes, and banding together of people to protect their own interests. So the world becomes more and more divided as people club together in order to overcome their insecurity and their fear.

When we are afraid, we feel threatened by what is happening around us, we each close up more within ourselves. In India, where, in the past, people suffered little from envy, where they looked upon those who had more than themselves with peaceful eyes and gentle contentment, one now finds an increase of aggression and jealousy arising from fear. When we feel threatened, we make our shell stronger and strengthen the affiliations we think will protect us. Our prejudices are also strengthened. When life is full of fear and pressure, the human mind loses its sense of perspective. In the absence of perspective there can be neither an understanding of what is happening nor the possibility of resolving difficulties. We cannot see danger ahead if our eyes are focused shortsightedly on the immediate area in front of us. If we are anxious about a little mud on the road and walk with our head bowed, we may fall over a precipice. The need of the moment that monopolizes the attention makes it impossible to see what needs to be seen, much less find an answer to the problem. The shortsightedness of our self-preoccupation cripples our vision and incapacitates our mind.

The age-old human problem requires for its solution a mind that has width, comprehension, and keenness of attention. The problem is how to live in peace and harmony with other people, with nature, with oneself, and to let all that is best within unfold into a state of beauty and perfection.

The present-day world abounds in symptoms of shortsightedness. Specialization is one form. When the mind moves in a groove, it becomes indifferent to other issues. The chemist who produces deadly chemicals is capable of being totally unconcerned with what happens when these chemicals are released. Animals and birds may be killed, the earth may be despoiled and the climate altered, but the chemist is interested only in the manufacture of the chemicals. A well-known nuclear scientist is supposed to have said that he was concerned only with making the bomb and did not care where it fell.

Another common expression of shortsightedness is the making of compartments. The secular, for example, becomes divided from the religious. The mind is satisfied with some religious activity such as going to a temple or attending a meeting, while the rest of life goes on unrelated to the prayers that have been recited or the lecture that has been listened to. Thus, the thought and the act, the preaching and the practice become divided. Social service, too, can be set apart from the quality of the personal life. A so-called humanitarian may be arrogant, conceited, even cruel in personal relationships. One can be kind to animals and hard on human beings, or kind to human beings and indifferent to animals and plants.

Yet another symptom of shortsightedness is that of living like a frog in a well. This exhibits itself in exclusive association with one's peer-group, whether composed of hippies, intellectuals, engineers, or something else. In India, the family becomes the circle within which all interests are concentrated—a group so important that nothing else matters.

Conceit arising out of being "modern" or "progressive" is another groove. The poet Kalidasa said that everything that is old is not necessarily good; nor is everything that is modern. Both progressives and traditionalists are carried away by petty notions that limit one's vision.

A mind partial to one thing or another cannot have perspective. The part to which it fixes itself may appear to be large, but it is still only a part. A mind that functions in bits and pieces, according to the expediency of the moment, is deluded because it cannot see the whole. To have a sense of perspective and to be aware of the wider issues means not only that the mind must not be partial, but that it must be sensitive. When there is insensitivity, there is shortsightedness. If the mind sees only the obvious, the concrete, if it cannot see what is subtle, what lies below the surface, if it cannot respond to the unsaid, to hints from within, surely it is "missing so much and so much." Wholeness requires that the mind and the heart become more sensitive.

As mentioned above, insecurity drives people into self-preoccupation. People relentlessly pursue objects of desire, whatever they can get, because they feel that in a little while these things may be lost to them forever. The drive towards pleasure, or any drive that is self-motivated, makes one insensitive. Insecurity makes one affirm one's position—makes it necessary to define oneself as a Muslim or a Jew or an Indian or something else. The identities which we give ourselves, the affirmations we make about our own personality, are all symptoms of shortsightedness born out of self-preoccupation and the self-motivation which creates insensitivity.

The true meaning of samnyasa is to abandon self-definition. The word samnyasa has become a mockery in the present day, a new form of self-indulgence, a game of putting on uniforms. But the true samnyasi does not define themselves in any fashion; they are not located in any particular spot; they can be of any nationality; they do not belong to any one religion. All forms of identity—all outward trappings and inner attachments—have to be put aside in order to be a samnyasi. Identity with a function, as a worker, an official, a rich man, a poor man, or identity with one's physical appearance arises, as mentioned earlier, out of certain conditioning factors that take place from birth. To be intelligent requires that one sees and discards all this.

The first object of the Theosophical Society speaks of forming a nucleus of Brotherhood without distinction of race, creed, caste, sex, or color. There are other distinctions it does not mention. It implies that one has to go deeply into oneself in order to negate all those values, ideas, and notions which, lying hidden within the mind, project the objects of desire and the many illusions to which we attach ourselves. To be a Theosophist means to be free, to learn to look intelligently, to find that state within oneself which is purity and austerity. If we can discard pursuits, if we cease to create illusions for ourselves, if we do not affirm our personality in any way, we achieve utter simplicity. Simplicity is not a matter of outer dress or of circumstance. It is a state that arises when we hold on to nothing. It is in this stage of simplicity, of samnyasa or austerity, that we can discover the wisdom to resolve the problems of humanity and make the world a better place. The urgency for bringing about such a change is beyond question.