Printed in the Spring 2025 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Lachman, Gary, "The Vision of W.B. Yeats " Quest 113:2, pg 18-22

By Gary Lachman

On the afternoon of October 24, 1917, just four days after their wedding, Georgie Hyde-Lees, the young bride of the middle-aged poet W.B. Yeats, decided to try her hand at automatic writing, the practice of allowing spirits to communicate through the written word.

On the afternoon of October 24, 1917, just four days after their wedding, Georgie Hyde-Lees, the young bride of the middle-aged poet W.B. Yeats, decided to try her hand at automatic writing, the practice of allowing spirits to communicate through the written word.

The newlyweds were not unfamiliar with the spirit world. Yeats had for years explored it and other esoteric realms through his membership first in the Theosophical Society (during which he met H.P. Blavatsky) and then in the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, which counted among its devotees the notorious Aleister Crowley. Yeats had also attended seances and spent hours poring over reports from the Society of Psychical Research, searching for evidence of the unseen. Georgie too was well versed in astrology, folklore, and spiritualism, and was also a member of a later branch of the Golden Dawn.

But the impetus for this foray into the “other side” was something less scientific and altogether more personal. The newlyweds’ honeymoon was in danger of being aborted. Just three weeks earlier, Yeats’ offer of marriage had been rejected by Iseult Gonne, the young daughter of Maude Gonne, the actress and Irish revolutionary Yeats had loved for years. Now, on their own honeymoon, Georgie found the poet brooding and depressed over the rejection. One can only imagine how she felt, married on the rebound, and with a husband more than twice her age experiencing buyer’s remorse. (She was twenty-five; Yeats, fifty-two.)

Communicating with spirits might not seem the first option for livening up what threatened to become a regrettable situation. But Georgie knew that Yeats had an insatiable interest in the magical and mystical; she also knew that all good poets need a muse. If spirits couldn’t lift his spirits, nothing would.

She was right. Almost as soon as she allowed her hand to hover over the blank page, messages came from entities Yeats would call “the instructors.” “What came in disjointed sentences, in almost illegible writing,” Yeats wrote, “was so exciting, sometimes so profound,” that he persuaded his young bride to devote a few hours a day to receiving these messages. What emerged so convinced Yeats of its importance that after spending some days studying the material, he declared that he would devote “what remained of life to explaining and piecing together” these mysterious communications.

The spirits (or whoever was responsible for the messages) disagreed. “No,” they said (there was often more than one communicator), “we have come to give you metaphors for poetry” (Yeats, 8).

As the poet and Yeats scholar Kathleen Raine points out, this caveat has allowed scores of literary critics to ignore Yeats’ genuine dedication to the philosophia perennis, seeing it only as material for his verse. Although much of Yeats’ poetry is opaque without a knowledge of its roots in his Hermetic studies, those studies were undertaken not solely to acquire poetic metaphors but to gain knowledge of the mysteries behind the sensible world. As Georgie’s hand, guided by her instructors, scribbled furiously, Yeats saw that a good deal of that knowledge was coming through in spades.

Soon it was decided that writing was too laborious, so the spirits took to communicating by voice. Georgie would sink into a half-sleep (the hypnagogic state that Yeats himself often explored), and speak—or, rather, the spirits would: different ones at different times. Throughout these proceedings, and during the years they took place (the voices stopped in 1920) all sorts of poltergeist phenomena appeared: strange whistling, smells of incense, violets, or roses, but also burnt feathers and, even more pungently, cat droppings.

What also seems like classic poltergeist behavior is the admission by the spirits that they would deceive Yeats if they could. Often communication would be stalled because of the interference of spirits Yeats called “the frustraters,” who would relate misinformation (much as we find on social media). Yeats came to see the truth of the remark by his contemporary G.K. Chesterton that, whatever the source of the phenomena taking place at seances, one thing was true: it told lies—something Blavatsky had said years earlier.

Nevertheless, Yeats discovered that material from these semitrance states seemed to relate to an idea he had put forth in his early poetry collection Per Amica Silentia Lunae: some men develop through their battles with themselves, others through their battles with the world (what Jung would have called the “introverted” or “extraverted” paths).

Nevertheless, Yeats discovered that material from these semitrance states seemed to relate to an idea he had put forth in his early poetry collection Per Amica Silentia Lunae: some men develop through their battles with themselves, others through their battles with the world (what Jung would have called the “introverted” or “extraverted” paths).

The spirits took up this notion, and with it developed what Yeats called “an elaborate classification of men” according to their type. That elaborate classification ultimately became one of the most fascinating, if baffling, attempts at an esoteric knowledge system in modern times. Yeats put forth this system in his work, simply entitled A Vision.

A Vision appeared in different editions, with many changes, alterations, and additions between them. It was first privately printed in 1926, in an edition of 600 copies distributed to subscribers. It received few reviews and made little impression at the time. A Vision appeared again in 1937, in a very different form than its first edition. (It is this edition that I refer to here.) In 2008, the original 1926 version appeared as volume 13 of the Collected Works of W.B. Yeats, published by Scribner.

At first, Yeats’ attitude to the work was somewhat casual, almost apologetic, rather like C.G. Jung’s attitude to his monumental but highly personal journal The Red Book. (Indeed Yeats and Jung, although ostensibly ignorant of each other’s work, had much in common, including an equivocal public attitude toward the occult, as we see in James Olney’s 2022 book The Rhizome and the Flower). Although Yeats made no secret of his interest in spiritualism, Theosophy, and other esoteric studies, he retained a highly skeptical mind, something that comes through in his poetry.

Eventually, the material Georgie produced would fill some fifty notebooks, thousands of pages containing not only the messages from the “instructors,” but also strange geometric designs. These symbolized the processes that Yeats came to see at work not only in the lives of individual men and women, but also in what they would experience in the afterlife. Moreover, the system emerging in A Vision was full of historical cycles, hearkening back to the ancient idea of the Great Year and the ages of gold and iron, but also reminiscent of that remarkable work by Yeats’ German contemporary Oswald Spengler: The Decline of the West. Spengler argued that the civilization which had emerged from the Renaissance, and had been dominant since, was at an end. (The first volume of the book appeared at the end of World War I, apparently corroborating Spengler’s idea.) Yeats agreed, but the coming “new age” predicted in A Vision differed considerably from the one that Spengler believed was on its way.

As the material grew, the spirits asked Yeats to help them by reading deeply in philosophy, history, and the esoteric traditions, something with which he was already very familiar. Communication continued through his and Georgie’s dreams, but the more Yeats read, the more complex and baffling the messages became. The dialogue proceeded in the form of questions and answers, Yeats asking for clarification of some point in the preceding exchange, and the voices picking up from there. In a sense, Yeats was trying to create his own form of astrology. He had once asked whether it were possible for a “prophet” to “prick upon the calendar the birth of a Napoleon or Christ” (Yeats, 9). Yet the elements in this system were not the constellations and planets, although, as the scope of the communications expanded, they too would find themselves brought into the mix.

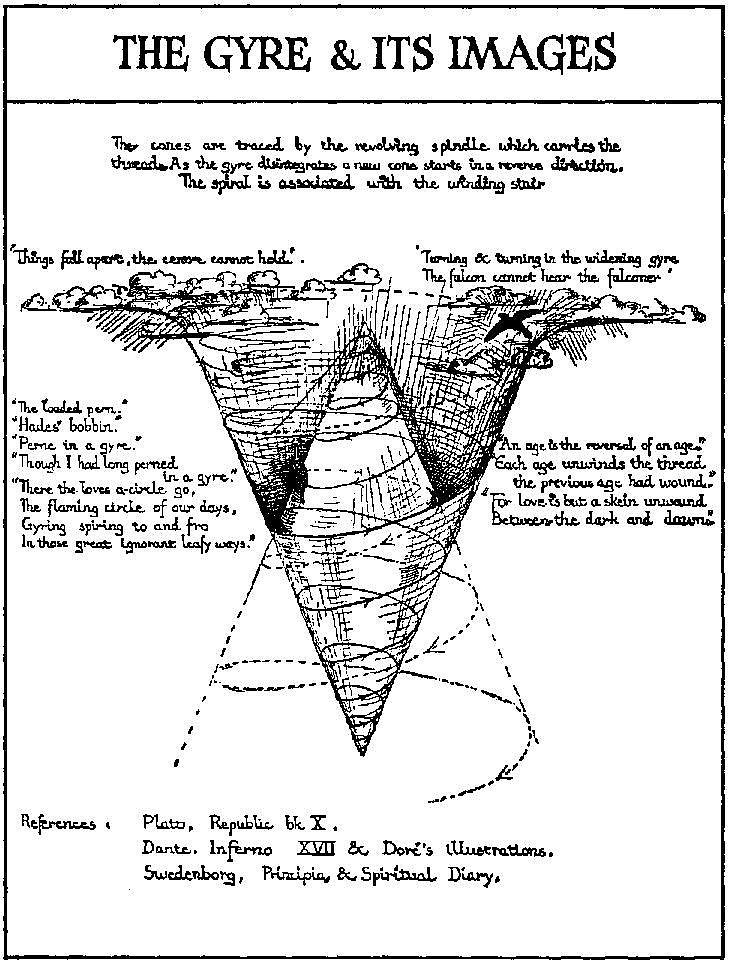

The fundamental elements of Yeats’ system are the twenty-eight phases of the moon, the four “faculties” that he ascribes to men and women which determine their path in life, and the strange “gyres,” or spiralling patterns, represented by intersecting cones, with the apex of one touching the base of the other, each one turning in the opposite direction (deosil and widdershins, or clockwise and counterclockwise), as if each cone were screwing itself into the other. The “objective” cone relates to space; the “subjective” cone to time. The “subjective” cone is one of emotion and the “inner” world; the “objective” cone is one of reason and the “outer” world. Their intersection is a kind of perpetual tussle, with one gaining the upper hand only to lose it to the other, which loses it in turn, and so on. The “objective” cone possesses what Yeats calls a “primary tincture”; the subjective cone, an “antithetical” one. “Tincture” here means a kind of “essence.” The “primary tincture” is one of law and logic; the “antithetical tincture” is one of imagination and emotion.

|

|

| A representation of the dual interpenetrating gyres of A Vision. Note the opening verses of Yeats' "Second Coming" above the top gyre. | |

Gyres appear in Yeats’ poetry. “The Second Coming,” perhaps his most famous poem, begins: “Turning and turning in widening gyres / The falcon cannot hear the falconer.” The poem announces the end of one age and the beginning of another: a more brutal one, when “things fall apart,” “the centre cannot hold,” and “mere anarchy is loosed upon the world.” Yeats believed that when one civilization has reached its end, an opposite or, as he calls it, “antithetical” one begins; he refers to the Pre-Socratic philosopher Empedocles, who believed that the fundamental reality was the eternal struggle between “discord” and “love,” fragmentation and unity, and that in different ages one or the other is dominant. According to Yeats, after two millennia the Christian era is reaching its end, and an age, not of love but something less comforting, is “slouching toward Bethlehem” to be born. It isn’t coincidental that Yeats wrote the poem in 1919, in the aftermath of the First World War. Its twenty-two lines convey the gist of Spengler’s massive tome with concentrated force.

The gyres represent not only historical cycles, but also the patterns of individual lives. Individuals themselves, as mentioned, possess four “faculties,” which Yeats calls “Will,” “Mask,” “Creative Mind,” and “Body of Fate.” Yeats’ four “faculties” bear comparison with Jung’s four functions: thinking, feeling, sensing, and intuition.

Although exactly what Yeats’s faculties are is (like much else in A Vision) explained rather vaguely—the compactness of much of Yeats’ poetry is rarely present in his prose—we can, I think, get a rough idea of what he means.

By Will we can understand the sort of person one is: bold, shy, hedonistic, ascetic, emotional, withdrawn, and so on.

For Yeats, the Mask is the face one wears in public; as his fellow poet T.S. Eliot says in “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” we “prepare a face to meet the faces that we meet.” Jung knew of the Mask too: he called it the “persona,” which is often very different from what he called “the Self.”

Creative Mind is one’s inherent creative style—contemplative poet or histrionic self-dramatist, bohemian artist or disciplined musician.

Body of Fate seems self-explanatory. It is destiny, or rather, the life events against which one fulfils one’s destiny—or not. Both the Mask and the Creative Mind can be expressed in their “true” form or their “false” one.

The four “faculties” are perched, as it were, on the opposite ends of the base of each cone. Picture two triangles intersecting each other, their apexes sideways, with Will and Creative Mind at the opposite bottom corners of one, and Body of Fate and Mask in the same position on the other.

If this isn’t complicated enough, the gyres turn, and the four faculties engage in a kind of struggle, either internal or external, against the backdrop of the twenty-eight phases of the moon. Along with the illustrations of the opposing cones, Yeats provides what he calls the “Great Wheel” of the lunar cycle.

This starts at Phase One, the new moon, which Yeats calls a state of “complete objectivity.” As the moon waxes, it passes through the next phases until we reach Phase Fifteen, the full moon, which is “complete subjectivity.” As in Phase One, in Phase Fifteen, “Unity of Being,” is achieved. As the phases continue, with the moon waning, counterclockwise, that unity is lost, until at Phase Twenty-Two, a stage of “the breaking of strength,” fragmentation sets in.

To show how this process appears in individual lives, Yeats offers examples, some of famous literary or political figures, some no longer so well known, some just abstract types, referring to “a certain actress” or “some beautiful women.” (Once again, the similarity to Jung is clear: A Vision can be read as Yeats’ Psychological Types, the book in which Jung illustrates the different types of personality created by the interaction of his four functions, and the opposition of the introverted and extraverted attitudes toward life.)

As an example of an individual at Phase Twelve, Yeats offers the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche (Yeats, 126‒29). Yeats calls the Will at Phase Twelve “the Forerunner,” which seems apt for Nietzsche’s belief that he was writing for the future: as he says in The Anti-Christ, “only the day after tomorrow belongs to me” (Nietzsche, Anti-Christ, 114). Nietzsche looked to the future for the arrival of the Übermensch, or “overman”—often translated as “superman”—an individual embodying the next stage in human evolution. If expressed truthfully, the Mask at this phase is “self-exaggeration.” Nietzsche’s remark that he was not a man, but “dynamite,” and that he philosophized with a “hammer” may seem on target here. If expressed falsely, the Mask is self-abandonment; does Nietzsche’s tragic collapse into madness qualify here?

A true Creative Mind at Phase Twelve produces “subjective philosophy,” which most academic philosophers would agree characterizes Nietzsche’s work. If false, it results in a “war between two forms of expression.” This doesn’t seem immediately clear until we remember that in his last years, Nietzsche labored to write a magnum opus, a systematic presentation of his philosophy, spelling out what he called the “revaluation of all values.” Yet he was unable to complete it; what he left in his notebooks was published after his death as The Will to Power. Instead, he reverted to form (he was never a systematic thinker) and in a flurry of frenzied writing, produced the incandescent works of his last days, including Twilight of the Idols, The Antichrist, and his strange autobiography, Ecce Homo, all short works written in his aphoristic, “telegraphic” style, in which he attempted to say in “ten words” what others “do not say in a whole book.”

The Body of Fate at this phase is one of “enforced intellectual action,” which sums up Nietzsche’s life; as he wrote in The Gay Science, “I still live; I still think. I still have to live, for I still have to think.” (Nietzsche, Gay Science, 223).

Phase Thirteen gives us “the Sensuous Man” as characteristic of the Will at this phase. The examples Yeats gives again seem to suit. He offers the French poet Charles Baudelaire (1821‒65), as well as two of Yeats’s contemporaries, the poet Ernest Dowson (1867‒1900) and the artist Aubrey Beardsley (1872‒98). All were indeed “sensuous” men. Dowson, an opium addict and alcoholic who died at thirty-two, was a fellow poet, one of the “decadent” school of the late nineteenth century, whom Yeats called “the tragic generation.” Dowson is most remembered today for the poignant lines from his poem “Vitae Brevis Summa”: “They are not long, the days of wine and roses: / Out of a misty dream / Our path emerges for a while, then closes / Within a dream.”

Beardsley was associated with “the naughty nineties,” with Oscar Wilde and The Yellow Book, famous for its fin de siècle eroticism. His fine black-and-white illustrations, frequently featuring sexual and what we today would call “transgressive” subjects, scandalized his contemporaries.

Baudelaire can be considered the father of the decadent movement, of which Dowson and Beardsley, a couple of generations later, were a part. As its title suggests, Les Fleurs du Mal, “The Flowers of Evil,” Baudelaire’s most famous work, celebrated the dark, seductive attraction of sin and the forbidden. Like Dowson, Baudelaire experimented with drugs and was a member of the notorious Club des Hashichins in Paris, along with Victor Hugo, Arthur Rimbaud, and Honoré de Balzac.

The Mask in this phase in its true form is “Self-expression,” which Baudelaire certainly achieved. Yet the false form, “Self-absorption,” may suggest his obsession with sin. Certainly the false form of the Creative Mind, “morbidity,” suggests this preoccupation, since for all his celebration of evil, Baudelaire was crushed by a perpetual sense of being cursed.

The Body of Fate of this phase, “Enforced love of another,” fits his profile too. For years Baudelaire was enthralled by the mulatto woman Jeanne Duval and dependent on a masochistic relationship with her. Although beautiful and exotic, Jeanne was illiterate, unfaithful, malicious, and for most of the time drunk. Sadly, like Nietzsche, Baudelaire succumbed to syphilis, dying at the age of forty-six.

Other examples seem equally apt. At Phase Twenty we find “the Concrete Man,” with Shakespeare, Balzac, and Napoleon as examples (Yeats, 151). We might find this an odd assortment, but the “worlds” of all three were very “concrete.” Shakespeare’s and Balzac’s worlds are the epitomes of a kind of literary realism, with all the varieties of human characters appearing in Shakespeare’s plays and Balzac’s Comédie humaine. Both created densely populated fictional realms—Promethean attempts to reproduce real life in words. And the “concreteness” of Napoleon’s “world,” that of the Europe he conquered, seems self-evident.

Phase Twenty-One gives us “the Acquisitive Man,” whom Yeats exemplifies in his contemporaries, the playwright George Bernard Shaw and the novelist H.G. Wells (Yeats, 154). Neither was acquisitive in the usual sense of the world, of acquiring possessions or money, although both were very successful. Both did acquire vast learning and knowledge, and both looked toward socialism, which they regarded as a rational, logical approach to politics, as the cure for the acquisitive society in which they lived. Yeats considered them both as examples of the age of logic and reason that he believed (or at least hoped) was coming to an end.

Although they often disagreed on the details, Shaw and Wells believed in the notion of progress, of society’s advance through intelligence and reason. By contrast, as Kathleen Raine writes, Yeats “foretold a New Age which was to be characterised by a reversal of the premises on which our post-Renaissance civilization is founded” (Raine, From Blake to “A Vision,” 5). Those premises were the body of ideas that were introduced with the rise of science and the materialism that followed.

Yeats shared Spengler’s idea that there is no such progress, that “Greece was no advance on Persia”; nor was the “scientific age” a sign of progress over the “age of faith” it followed. For Yeats, it was more of a sign of “regress,” and he considered three centuries of scientific materialism as “provincial” when compared to the millennia of belief in the reality of spirit that preceded them.

Civilizations come to an end, Yeats believed, when “they have given all their light, like burnt out wicks,” and, like Spengler, Yeats thought our own candle was just about out (Raine, W.B. Yeats, 2). Although poems like “The Second Coming” seem to announce a darker time, Yeats did foresee a return of an age of imagination and poetry after one of logic, mechanics—the quantifiable universe of Newton. He did not prick upon a calendar a date for its arrival (although A Vision is full of references to the Platonic year, the precession of the equinoxes, and other versions of cyclical time), but he did believe it was on its way.

Had Yeats lived to see the occult revival of the 1960s, in which his influence and that of his fellow members of the Golden Dawn would play no small part, and in which the coming age of Aquarius featured prominently, he might have thought his prediction was coming true. Those heady days are long past, and it is nearly a century since A Vision was first published. But it seems clear that we are going through some shift in history in our own time. Let’s hope it will bring something closer to what Yeats had in mind in A Vision, rather than that rough beast making its way to Bethlehem.

Sources

Nietzsche, Friedrich. The Gay Science. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Vintage, 1974.

———. Twilight of the Idols and The Anti-Christ. Translated by R.J. Hollingdale. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books, 1977.

Olney, James. The Rhizome and the Flower: The Perennial Philosophy—Yeats and Jung. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2022.

Raine, Kathleen. From Blake to “A Vision.” Dublin: Dolmen Press, 1979.

———. W.B. Yeats and the Learning of the Imagination. Ipswich, UK: Golgonooza Press, 1999.

Maurice Nicoll: Forgotten Teacher of the Fourth Way. New York: Collier, 1970.

WB. Yeats. A VisionA Vision

Gary Lachman, a longtime contributor to Quest, is the author of several books about consciousness, culture, and the Western esoteric tradition, including Dreaming ahead of Time; The Return of Holy Russia; Dark Star Rising: Magick and Power in the Age of Trump; Lost Knowledge of the Imagination; and Beyond the Robot: The Life and Work of Colin Wilson. His latest book, Maurice Nicoll: Forgotten Teacher of the Fourth Way, was reviewed in Quest, winter 2025.