Printed in the Fall 2021 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Sorkhabi, Rasoul, "Zoroaster: The First Philosopher and His Theosophical Revolution" Quest 108:4, pg 23-28

By Rasoul Sorkhabi

Spiritual teachers may be categorized into personal teachers and teachers of teachers, whose influence permeate the intellectual history of humankind. Zoroaster, whose theosophical doctrines (from the Latin doctrina, “teaching”) and contributions are analyzed here, belongs to the latter category.

Spiritual teachers may be categorized into personal teachers and teachers of teachers, whose influence permeate the intellectual history of humankind. Zoroaster, whose theosophical doctrines (from the Latin doctrina, “teaching”) and contributions are analyzed here, belongs to the latter category.

When I was a young boy growing up in Iran, we learned only briefly about Zoroaster as the prophet of a religion prevalent in ancient Iran (Persia) before the coming of Islam in the seventh century. Later, while living in India, I came across the Zoroastrian Parsi population, whose ancestors migrated from Iran to the western coasts of India in several waves over the centuries in search of religious and social freedoms. In 1879 H.P. Blavatsky and Henry Steel Olcott encountered an educated and entrepreneurial group of Parsis in Bombay, some of whom actually helped build the headquarters of the Theosophical Society in India. The vibrance and contribution of the Parsis have continued to our day: the late singer Freddie Mercury, of the rock band Queen, who came from a Parsi family, is probably the best known.

Nevertheless, Zoroastrians currently constitute a small minority in the world, numbering only 100,000 to 200,000. This, however, should not mask the significance of Zoroaster’s teachings. A large number of books on Zoroastrianism range from scholarly translations of the Avesta (Zoroastrian scriptures) to popular introductions to Zoroastrian beliefs and practices.

In this article, I focus on Zoroaster’s philosophical underpinnings in order to explore two specific questions: What was the social and cultural environment in which Zoroaster began his ministry? How did his teachings shape religious thinking?

These questions take us to the heart of Zoroaster’s teachings and uncover a great deal of forgotten history. My basic thesis here is not historical, but the realization that what Zoroaster taught some three millennia ago still pertains to the philosophical discourse, spiritual quest, and social struggles of our time.

Who Was Zoroaster?

Despite a series of Greco-Persian wars in the sixth through the fourth centuries BC, ancient Greek thinkers, including Plato, had high regards for Zoroaster. Zoroaster is a Greek name for Zarathushtra, probably meaning “the owner of golden or yellow (zarath) camels (ushtra).” Zoroaster’s family name was Spitama (“white”), after his ninth ancestor, possibly referring to their skin color. His father was Pourush’aspa (“owner of many horses”) and his mother was Doughdova (“milkmaid”). All these names indicate a pastoral lifestyle.

At age thirty, Zoroaster experienced a revelation that instructed him to be the messenger of divine teachings to his people. He experienced much hardship and rejection. At age forty, however, in the Iranian capital Balkh (in today’s Afghanistan), Zoroaster convinced King Vishtaspa (Goshtasp, “owner of swift horses”) of the truth of his religion. Zoroaster died at age seventy-seven.

Many scholars estimate that Zoroaster lived in the second millennium before Christ in northeast Iran or Central Asia. Zoroaster’s hymns or the Gathas (Anklesaria, Poor-davood) are included in the Yasna—the oldest part of the Avesta. They have remarkable linguistic resemblance to the Hindu Rig Veda, composed by the “seers” (rishis) in 1500–1000 BC.

From Animism to Monotheism

Zoroaster grew up in a polytheistic and animistic culture of the Aryan tribes. As recorded in the Gathas (Yasna, 33:6), he was a high priest (zaotar). In those days, the population was divided into four classes (similar to the Indian caste system): rulers, priests, warriors, and common people (nomads, ranchers, farmers, and craftsmen). Zoroaster sided with the common people—the poor and the oppressed (drighu, Yasna, 34:5)—and criticized princes (kavi) and priests (karapan) for their violence, corruption, oppression, injustice, and cruelty to people, land, and animals (Yasna, 44:20).

Although Zoroaster knew about the psychedelic plant juice haoma (soma in Sanskrit), his Gathas do not favor its consumption—strikingly different from a large number of hymns in the Rig Veda, which extol soma. Similarly, Zoroaster is not in favor of sacrifices, even though animal sacrifice has been practiced somewhat by Zoroastrians.

The Avesta connects the slaying of the primordial Bull, which was the companion of the First Man (gayo maretan, “living mortal”), to the work of the evil force. From the slaying of the Bull, the Avesta reports, arose all the animals and plants on the earth. In the Gathas, Ga’ush Urva (“cow’s soul”) represents the soul of all animals and plants as well as the earth. Ga’ush Urva complains to God: “Why did you create me? I am crushed by all this anger and violence, and have no protector.” Her prayer is answered, and Zoroaster, “blessed with sweetest words” (poetry), is assigned to be her protector, but Ga’ush Urva objects that a weak man, rather than a strong ruler, is to protect her. Eventually, she agrees to it after learning that Good Mind (vohu manah) is behind Zoroaster (Yasna, 29:1–10). Vohu Manah (bahman in modern Persian) is the link between God and Zoroaster, like the Holy Spirit in Christianity and the archangel Gabriel in Islam.

Zoroaster reinterpreted all the animistic deities related to fire, earth, water, plants, animals, and metals as six archangels (amesha spenta, “immortal brilliant or holy beings”) or divine aspects or powers (yazata, “worthy of veneration”) of the One God. In the latter group, Zoroaster includes several gods previously worshiped, including Mitra (god of light, covenant, love, war, and farming, depending on various cultures and periods) and Anahita (goddess of sky, water, fertility, and purity).

This change from polytheism to monotheism was a paradigm shift in human thought. For one thing, it provided a sense of union and brotherhood among all humans. Zoroaster detached the forces of nature and their associated deities from the violence and brutality committed in their names.

A number of philosophers and historians of science (Hooykaas, Jaki, and more recently Schellenberg) have noted that science has rapidly progressed in periods or cultures in which the idea of a single wise God is prevalent. Historical cases support this view. Rational philosophy in ancient Greece grew when philosophers were freed from intellectual shackles of the Pantheon gods. The Arabs embraced science and learning after the advent of monotheistic Islam. The founding fathers of the Scientific Revolution in Europe, like Isaac Newton, despite their opposition to the church’s authoritarianism, considered their scientific research as a rational way to understand God’s design in creation.

Why should monotheism promote science? Unlike the belief in many gods in nature, the idea that a single omniscient god has created and designed the universe is compatible with the basic assumptions of science: order, law, unity, and predictability.

Mind Is Deeper than Matter

|

|

|

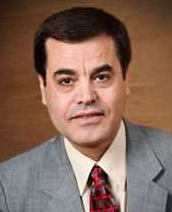

Figure 1.The Avestan faravashi (the ideal or spiritual human) is the best-known Zoroastrian symbol, dating back to the fifth century BC. The symbol is found on walls of archeological buildings in Iran as well as modern Zoroastrian fire temples. This illustration, dating from 1947, comes from the town of Taft in Iran. |

According to Zoroaster, reality or existence has two aspects or modalities: mainyu (minu in modern Persian), mind, idea or consciousness; and geteh (giti), the physical or material world. The parallel concept in the Rig Veda is the purusha-prakriti pair, as elucidated by Richard Smoley in The Dice Game of Shiva.

The words mind and mental share the same Indo-European roots with the Avestan mainyu and the Sanskrit manas. Another Avestan term for the realm of mainyu is faravashi, the archetypal world where God created all things over 3,000 years before they were manifested on the earth.

Some scholars hold that Plato’s theory of ideal forms or universals was influenced by Zoroastrian teachings (Chroust, Kingsley, Panousi). Plato may have learned about Zoroaster through the Ionian Greek philosophers, particularly Pythagoras (Guthrie, Riedwig) and Heraclitus (Honderich, Preus), who had studied with Zoroastrian magi (priests). Aristotle in his Metaphysics (Book 1, 987) states that Plato had studied the philosophies of Heraclitus and Pythagoras, besides that of Socrates. Indeed, the first generation of Greek philosophers were from Ionia (the western coast of Anatolia in present-day Turkey), which was ruled by the Persian kings (the Achaemenid dynasty) from 540 to 335 BC, when the Persian empire itself was conquered by Alexander the Great. Greek philosophy up to Aristotle was largely developed during that period (Boyce 150–63).

Plato, from age twenty-eight, when his teacher Socrates was put to death in Athens in 399 BC, to age forty, when he returned to Athens to establish his Academy, was traveling and studying. In the Alcibiades, Plato mentions the name of Zoroaster. There are also reports that in the last days of his life, Plato received a Persian magus who had traveled to Athens to visit him (Kingsley). All these indicate Plato’s knowledge of Zoroastrian philosophy.

The concept of mainyu or faravashi is similar to what contemporary physicists like Albert Einstein and Stephen Hawking call the Mind of God. Although the scientists use this expression metaphorically, metaphors do indicate some hidden and valid points. Indeed, the relation of mainyu to modern physics goes deeper. Quantum physics has demonstrated that although there are tangible material things at the scale of our normal observation, at subatomic levels the universe is a unified field of vibrations or waves, beyond which we have no knowledge. As we go deeper, matter disappears into “effects” of underlying and mysterious realms. This is also true as we go back in time, to the moment of the big bang. The physical universe thus appears to be an evolutionary manifestation of a fundamental and universal mind. Zoroaster called it spenta mainyu (“benevolent mind”), which is the creative principle of God (Yasna 43:6; 44:7; 51:7).

In The Mysterious Universe, first published in 1930, pioneering astrophysicist Sir James Jeans writes: “The stream of knowledge is heading toward a non-mechanical reality; the universe begins to look more like a great thought than like a great machine. Mind no longer appears to be an accidental intruder into the realm of matter, we ought rather hail it as the creator and governor of the realm of matter” (Jeans, 186).

Jeans was not and is not alone in this view. In his own generation, physicists like Max Planck, Einstein, Arthur Eddington, Erwin Schrödinger, and Werner Heisenberg were on his side. Science itself has demolished the myth of materialism in the sense that the boundary between matter and nonmatter has become finer and blurred (Davies and Gribbin). Many eminent physicists, philosophers, and neuroscientists today suggest that at the very source and foundation, and in the very fabric of the physical world, lies consciousness or mind. In other words, consciousness does not blindly arise from the accidental assembly of unconscious bits of matter. It is embedded in all of existence and is manifested at various levels in myriad forms and modes. This philosophical view can be traced all the way back to Zoroaster and the Rig Veda.

For Zoroaster, however, the world is not merely a machine inhabited by a ghost. He felt a sense of immense reverence toward nature. In his religion, the four elements (akhshij)—earth, water, air, and fire—are all sacred and should not be polluted. Writing in the fifth century BC, Herodotus notes: “Persians have a profound reverence for rivers; they will never pollute a river with urine or spittle” (Herodotus, 64). Today, even secular biologists like E.O. Wilson acknowledge that without deeply felt care and reverence for the Creation (Wilson), we cannot solve our ecological crisis.

Lord of Wisdom

Like Sufis, who have ninety-nine names for God, the Avesta lists 101 names for various attributes and aspects of God. Of these, the single name that Zoroaster chose to represent his notion of God is Ahura Mazda (“lord of great knowing or wisdom”). This was indeed a paradigm shift in religious thinking three millennia ago; to this day, it has a modern tone. Astronomer Carl Sagan once said that he would accept the notion of God if God is defined as “the sum total of the physical laws of the universe,” because the fact that “the same laws of physics apply everywhere is quite remarkable” (Sagan, 149–50). Fifty years before Sagan, Einstein had remarked that “the eternal mystery of the world is its comprehensibility . . . The fact that it is comprehensible is a miracle” (Einstein, 292).

Of course, Zoroaster did not have a modern understanding of the laws of nature, physical constants, and scientific theories. However, through meditation, he had realized the amazing wisdom underlying and permeating the natural world. Zoroaster praised and celebrated this wisdom. In his Gathas, there are over 200 references to the name of God as Mazda, and indeed the original name for Zoroastrianism is Mazda-yasna (“wisdom celebration”). As Pliny the Elder remarked in his Natural History (8:30), one wonders if this term was the inspiration for the Greek word philosophia (“love of wisdom”), coined by Pythagoras (Kenny, 14).

What is the One that underlies the myriad phenomena in the world? Greek philosophers variously chose one of the four elements as the “first principle” (arche in Greek). Zoroaster did not stop at material monism, and instead underscored a universal benevolent Mind (spenta mainyu) emanating from Ahura Mazda as the primary principle of creation.

We see the influence of Zoroaster’s thinking on Heraclitus of Ephesus, an Ionian philosopher of the fifth century BC who rejected the gods of the Greek pantheon and instead believed in one God, whom he called to sophon (“the wise one”; Kahn). Heraclitus also posited logos (“word, reason, order”) as the creative principle of the world, represented by “ever-living fire” (a Zoroastrian motif) as the first material element, which gives rise to other elements (starting with smoke or air and then water and earth) as well as “warm” life. We similarly find a “central fire” in the Pythagorean cosmological scheme. In the third century AD, the Roman-Egyptian philosopher Plotinus, father of Neoplatonism and author of the Enneads, suggested a similar view: nous or logos (“consciousness” or “mind”) was the first emanation from the One God, from which proceeded the rest of creation.

|

|

|

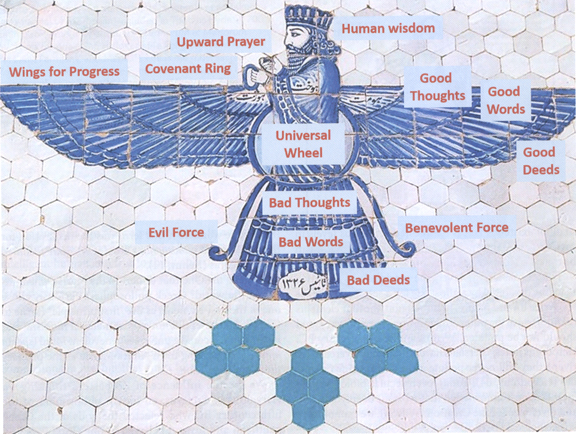

Figure 2. A sketch of a Zoroastrian fire temple near Baku (now capital of Azerbaijan) included in Thomas Hyde’s 1700 Latin book, Veterum Persarum et Parthorum et Medorum religionis historia (“The History of the Religion of the Ancient Persians, Parthians, and Medes”). Fire is the most sacred Zoroastrian symbol of divine light, wisdom, love, and life; it has a central place in Zoroastrian temples. Moreover, Zoroastrians pray five times a day toward the direction of the sun. This does not, however, mean that they worship fire or the sun, as is wrongly assumed. |

In the twelfth century, the Persian Sufi master Sohravardi integrated the Zoroastrian and Neoplatonic ideas in his philosophy of Illuminism (hikmat al-ishraq). He envisioned various levels of “being” as various degrees of “light.” God was the Light of the Lights, and Bahman (vohu manah) was the First Intellect or the First Ray emanating from God. This shows the undercurrent of Zoroaster’s philosophical influence down the ages.

Zoroaster’s praise of wisdom was not lip service; he truly believed in its power and significance, not only in the universe but also in religion. He recommends, “Listen with your own ears, and with a bright mind choose truth from false creed—each person for his own self, before the Final Judgment comes” (Yasna 30:2).

Imagine that you are a person living in a restrictive tribe three thousand years ago who hears that you are an intelligent human and free to think and choose. What a sense of dignity and empowerment you might have gained from these words!

Zoroaster uses two terms for the individual mind and wisdom: khratu for rational thinking (reason) and chista for penetrative knowledge (insight). These faculties, bestowed by Ahura Mazda upon all humans, are valuable companions in life, but they must be nurtured through learning and experience.

Religion Is Goodness

There is a beautiful story about Hillel the Elder, a Jewish sage of the first century BC. He was once challenged by a skeptic if he could teach the entire Torah in one sentence while standing on one foot. Hillel answered: “That which is hateful to you, do not do to another; this is the entire Torah, and the rest is its interpretation. Go study” (Talmud, Shabbat 31a).

If you put this question to a Zoroastrian, he or she would say: hu mata (“good or noble thought”), hukhta (“good speech”), and hu varashta (“good action”). Zoroastrians call their religion Beh Dini, “good religion,” not because they consider other religions to be bad, but because a true religion means being good. In the same vein, the Dalai Lama has often said, “My religion is kindness.”

Like in other religions, compassion (mehr, derived from Mithra) is highly praised in Zoroastrianism. Moreover, there is an organic relationship between compassion and goodness. Without good morals and behavior, compassion remains unrealized, abstract, and even perhaps an egoistic claim. Good thought, good words, and good deeds are thus an elegant garment that Zoroaster wishes to put on compassion.

What is the source of goodness? How do we know what is good? According to the Avesta (Yasna 26:4), the human body (tanu) is born with five internal forces: (1) ahu, life force; (2) daena, knowing through the spiritual eye or conscience; (3) budha, knowing through the senses and mental processes including reason and meditation (comparable to the Sanskrit buddhi); (4) orvran, the soul which is cultivated in life, for better or worse, and is subject to the Final Judgment, and (5) faravashi, the ideal or spiritual human accompanying the body as the guardian angel.

Of these qualities, daena, conscience, in particular guides all humans to know what is good, to be done, and what is bad, to be avoided. Like the body itself, daena, if left unprotected and exposed to destructive forces, cannot fully function. It needs to be nourished through customs, community, practices, and teachings.

Goodness is closely related to the concept of asha, perhaps the most important Zoroastrian word after the name of God. Asha, which appears 162 times in the Gathas, means “truth” in two different domains. Asha in the universe refers to law and order, which is explored through science. Asha in human affairs refers to righteousness and justice, which is realized through spirituality and social law. The opposite of asha is druj, literally, “lie or false” in a broad sense of the term—dishonesty, injustice, incorrectness, lying, harming and so forth. Druj is to be avoided. Herodotus (63) reports: “Persians consider telling lies more disgraceful than anything else.” In an inscription from the fifth century BC by the Persian emperor Darius I in his capital, Persepolis, we read this prayer: “May Ahura Mazda protect this country from enemy army, from famine, and from the Lie!”

Asha and druj stem from two opposite forces or qualities operating among humans ever since their appearance on the earth: the good force is Spenta Mainyu (benevolent mind), associated with Ahura Mazda, and the evil force is Angra Mainyu (“hostile mind”), personified in Ahriman (the Devil or Satan in Judaism and Islam). Humans, endowed with wisdom, conscience, teachings, and freedom, are engaged in the battle between goodness and evil.

Some may criticize Zoroaster’s thinking as dualistic and polarizing, but there is a sense of social realism in his teaching. The world is a blend of good news and bad news. We see both compassion and cruelty. Which side do you want to be on? This is Zoroaster’s question. In the face of all the ill and evil which we witness and which can indeed be overwhelming, Zoroaster insists that humans are not helpless or powerless: they can take life in their own hands and be on the side of good and light. This progressive way of thinking was indeed a liberating force in Zoroaster’s time; it always is. In his masterpiece Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche develops this concept as “the will to power.”

The duality of good and evil does not mean that Zoroaster believed in two gods, as is sometimes claimed. Ahriman is not a god. Time and again, Zoroaster uses the analogy of light and darkness for the relationship between Ahura Mazda and Ahriman. Darkness is the absence of light.

Dialectical thinking about the operation of opposites and the war of good and evil can be psychologically exhausting and depressing. Heraclitus, who viewed the world as a state of flux and change through the action of opposing forces, was known to be “the weeping philosopher” because of his melancholic views of life and humans (whom he avoided by living on mountains).

Zoroaster, by contrast, maintains an optimistic attitude toward life. He believes in the power of wisdom and work. He believes that truth and goodness eventually win because they are primordial and essential in human nature and have divine origin. Legend has it that when Zoroaster was born, he did not cry but laughed—a gesture of joy and optimism.

In Zoroaster’s life, we find the elements of what Joseph Campbell formulated as the Hero’s Journey. Zoroaster returned from this journey not only as a messenger, but also as a social reformer, poet, and philosopher. Zoroaster calls for both wisdom (mind) and goodness (heart), not separately but in combination—“the path of Good Mind” (Yasna, 34: 13).

Sources

Anklesaria, D.T., trans. The Holy Gathas of Zarathustra. Bombay: Rahnuma-e Mazdayasnan Sabha, 1953.

Boyce, M. A History of Zoroastrianism, vol. 2: Zoroastrianism under the Achaemenians. Leiden, The Netherlands: Brill, 1982.

Chroust, A.H. “The Influence of Zoroastrian Teachings on Plato, Aristotle, and Greek Philosophy in General.” In The New Scholasticism 54, no. 3 (1980): 342–57.

Einstein, Albert. Ideas and Opinions. Translated by Sonja Bergmann. New York: Three Rivers Press, 1982 [1954].

Guthrie, K.S., ed. The Pythagorean Sourcebook and Library. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Phanes, 1988.

Herodotus. The Histories. Translated by Aubrey de Sélincourt. London: Penguin, 1996.

Honderich, Ted, ed. The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2005.

Hooykaas, R. Religion and the Rise of Modern Science. London: Chatto and Windus, 1972.

Jaki, S. The Road of Science and the Ways of God. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1978.

Jeans, James. The Mysterious Universe. 2d ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1942.

Kahn, C.H. The Art and Thought of Heraclitus: An Edition of the Fragments with Translation and Commentary. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979.

Kenny, Anthony. A New History of Western Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010.

Kingsley, Peter. “Meetings with Magi: Iranian Themes among the Greeks, from Xanthus of Lydia to Plato’s Academy.” In Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society, 5 (1995): 173–209.

Panoussi, Erwin. The Influence of Persian Culture and Worldview Upon Plato [in Persian]. Tehran: Iranian Institute of Philosophy, 2002.

Poor-davood, I., trans. Gathas [in Persian]. Tehran: Asatir, 1999.

Preus, Arthur. Historical Dictionary of Ancient Greek Philosophy. Lanham, Mass.: Rowman & Littlefield, 2015.

Riedweg, Christoph. Pythagoras: His Life, Teachings, and Influence. Translated by Steven Rendall. Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 2005.

Sagan, Carl. The Varieties of Scientific Experience: A Personal View of the Search for God. London: Penguin, 2006.

Schellenberg, J.L. Monotheism and the Rise of Science. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2020.

Smoley, Richard. The Dice Game of Shiva: How Consciousness Creates the Universe. Novato, Calif.: New World Library, 2009.

Wilson, E.O. The Creation: An Appeal to Save Life on Earth. New York: Norton, 2006.

Rasoul Sorkhabi, PhD, is a professor at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City. His life spans both East and West, as he has lived and studied in Iran, India, Japan, and the USA. This is his fourth article for Quest.