Spirit and Art: and the Puzzles of Paradox

By Van James

Originally printed in the January-February 2004 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: James, Van. "Spirit and Art: and the Puzzles of Paradox." Quest 92.1 (JANUARY-FEBRUARY 2004):4-9.

Today, the word spirit and the term spiritual are often reserved for the religion page of the newspaper, held captive at church, or exiled to New Age circles. But the questions of origin and birth, life and fertility, reincarnation and karma, and death and transformation have long been connected with spirit and have been communicated by means of art throughout the ages. Images of gods and goddesses, angels and demons may have given way to pictures of landscapes and abstract forms, but what can we understand from such changes? Throughout human history, spirit—the shamanic trance state, mystic revelation, divine inspiration, religious devotion, enlightened thinking, individual self-expression, the Spirit of the Age—has inspired change and transformation in human consciousness. Art is a picture of the spirit, in its many forms, articulating what it means to be human. Any period in history can show us through its art the nature of human consciousness at a particular time. From the Paleolithic era to the present time, art has acted as a self-portrait of the human condition and has served as a family album or picture book of our humanity. Shamanic art is one of the earliest such self-portraits, at its height during the Paleolithic era, between circa 42,000 and 12,000 BCE.

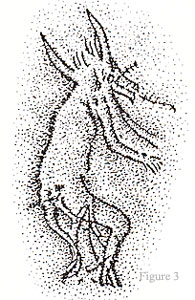

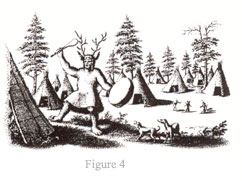

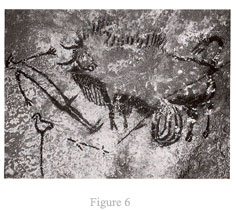

The term shaman, once used to describe the sages and medicine people of the Tungus tribes of Siberia, is now generally applied to certain people and practices found in almost all indigenous cultures throughout the world. Three essential elements are found in most shamanic traditions: (1) Shamans voluntarily enter visionary states of consciousness, during which (2) they experience non-ordinary realms of existence where (3) they gain knowledge and power for themselves or for their communities (Cowan, p.3). This journey into the supersensory, where the shaman is helped by spirit guides that appear most often in animal forms, usually leads to initiatory crisis, an experience of oneness with the fabric of the universe, and the ability to prophesy, heal, and control natural phenomena. The paintings of the Paleolithic caves may have been used in this connection. By depicting animal images in caves, the shaman may have stimulated a supersensory experience, entered the Otherworld by means of altered consciousness, and gained knowledge through this contact. The ritual artistic act of painting and drawing, together with other means, can be seen as a vehicle for paleo-shamanic practices.

Neuropsychological research distinguishes three overlapping yet discernible stages of trance experience. These begin with the "seeing" of geometric forms, such as dots, circles, crescents, zigzags, grids, or parallel and wavy lines. These forms, called phosphenes, have a luminous, brightly colored, pulsating character that fluctuates and metamorphoses. When the subject's eyes are open, these phosphenes are seen as though projected transparently upon surfaces such as rock walls. In the second stage of trance condition, some forms are given more significance than others and are seen as images of objects: A crescent may be a bowl, a zigzag may be a snake, and a grid a ladder. The third stage is entered by way of a tunnel or vortex experience, at the end of which a bright light is seen. The geometric forms of stage one transform into the lattice structure of the vortex into which the subject is pulled. Animal, human, and anthropozoomorphic figures begin to appear. Subjects feel by this third stage that they can fly and turn into animals or birds. Subjects become what they "see."

Jean Clottes and J. D. Lewis-Williams note that:

These three stages are universal and wired into the human nervous system, though the meanings given to the geometrics of Stage One, the objects into which they are illusioned in Stage Two, and the hallucinations of Stage Three are all culture-specific. . . a San shaman may see an eland antelope; an Inuit will see a polar bear or a seal. But, allowing for such cultural diversity, we can be fairly sure that the three stages of altered consciousness provide a framework for an understanding of shamanic experiences (p.19)

Although some researchers acknowledge the shamanic experience, it is often viewed as strictly hallucinatory and illusory in nature. This raises the question, Do we regard all shamanic experiences as hallucinatory or are there such things as valid and objective spiritual experiences?

During the Paleolithic era, entering a cave may have been equated with entering into deep trance by way of the tunnel experience. Images on the cave walls may have paralleled visions attained through altered states of consciousness, thereby providing a link between inner and outer experiences.

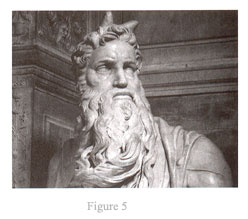

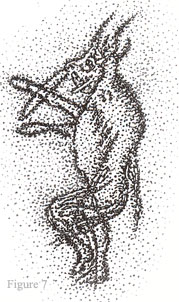

From this perspective, the antlers are a pictorial imagination of the formative life forces or chi connected to nerve activity, ideation, and sense perception. In this way, the antlers are an early artistic representation of what was perceived by primal humanity as radiating light that extends beyond and around the head. In other words, antlers and horns may indicate primal halos or auras. The halo is well documented in the history of art as a spiritual emanation surrounding the heads and bodies of buddhas, bodhisatvas, saints, and spirit beings. Antlers, horns, halos, and crowns are pictures of extrasensory capacities that stand behind the spiritual activity of thinking or knowing beings.

In the last line of the "Song of Amergin," one of the oldest remnants of Irish literature, Amergin,the Milesian bard, declares, "I can shift my shape like a god." This reference to the shamanic ability to shape-shift (the capacity to live as, identify with, and become one with other objects, beings, and phenomena) might also be translated as "I am the god who creates in the head of man the fire of thought." Put simply, this line might be paraphrased as "I am the fire of imagination" or "I burn with visions of the spirit world." Tom Cowan says about this phrase "Shapeshifting occurs in the head and is analogous to fire, the most radically transformative of the elements"(p. 35). All of these aspects, contained in this simple phrase by Amergin, pertain to the artistic rendering of the horned and antlered Animal Master. Life, thought, imagination, vision, fire in the head, and shape-shifting all relate to the antler-crowned shaman. So the question arises, Are these horns images of an extended vision, a new vision brought to birth in the Paleolithic caves through directed ritual artistic activity?

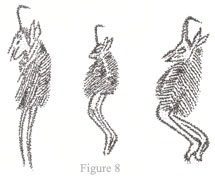

Images such as the Sorcerer of Les Trois Freres lead us to inquire whether such anthropozoomorphic figures represent (1) actual creatures that lived at the time, (2) fanciful beings invented by early humans, (3) hallucinations, (4) shamans in animal costume, (5) supersensory impressions of the shaman priests seen through the still-visionary consciousness of primal peoples, or (6) spirit beings. In different cases any one of these possibilities may be true. However, it is likely that in many cases early humanity is depicting the supernatural animal forces, the spirit guides, as they pertain to primal human experience.

Ritual masks, costumes, headdresses, crowns, capes, and other garments that were featured in cave art were probably donned as clairvoyant faculties began to decline among primal humanity. The art of costume initially had its place in cultic practices and probably approximated the actual picture formed in visionary experience. This is not to say that more mundane uses were not possible for sacred objects. However, the original inspiration for sacred objects such as the table (altar), the wheel (solar symbol), the dagger (sun ray), the headdress (halo), and clothing (body aura) appears to have been ritually motivated in connection with early sacred practices. The wearing of animal skins and horns had the significance of aiding the shaman on his or her vision quest or spirit journey to find the Animal Master and spirit guide. In this regard, Joseph Campbell points out:

The masks that in our demythologized time are lightly assumed for the entertainments of a costume ball or Mardi Gras—and may actually, on such occasions, release us to activities and experiences which might otherwise have been tabooed—are vestigial of an earlier magic, in which the powers to be invoked were not simply psychological, but cosmic. For the appearances of the natural order, which are separate from each other in time and space, are in fact the manifestations of energies that inform all things and can be summoned to focus at will. (p. 93)

Robert Ryan characterizes the shaman Animal Master's relationship to the cave as a "returning to the source of creation. The ithyphallic shaman's penetration of the maternal cave of power is a return to the deep structures of the human mind, the formal source of our experience, and, at the same time, to the cosmogonic source. For the revelation of the cave art is that the two sources, human and cosmic, have concentric centers and that their shared center is inwardly encountered and experienced by opening the eye of the soul ..." (p. 55).

To see the scene at Lascaux, one must pass through the great Hall of Bulls, an open chamber covered with exquisite large animal paintings—the largest of which are bulls—and proceed down a narrower, tunnel-like corridor to a well or shaft, "apparently the most sacred place in the sanctuary, rather like the crypt of an ancient church" (a staff, p. 28). One must descend into this shaft to view the shamanic scene.

The Animal Master, Sorcerer, or shaman is an important key to the imagery of prehistoric art as it captures in picture form the aesthetic missing link between the animal kingdom and the human being. Perhaps our long-lost ancestor is not the lower primate we've imagined for the past century and a half, but the elusive paleo-shaman Animal Master, as spirit and art have suggested for thousands of years.

References:

-

Campbell, J. Historical Atlas of World Mythology. (vol. I.) New York: Harper and Row, 1988.

-

Clottes, J. and D. Lewis-Williams. The Shamans of Prehistory. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1998.

-

Cowen, T. Fire in the Head: Shamanism and the Celtic Spirit. San Francisco, CA: HarperSanFrancisco, 1993.

-

Gimbutas, M. Language of the Goddess. London, England: Thames and Hudson, 2001.

-

Lorblanchet, M. quoted in R. Hughes, "Behold the Stone Age," Time, February 13, 1995.

-

Ruspoli, M. The Cave of Lascaux: The Final Photographs. New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1987.

-

Ryan, R. The Strong Eye of Shamanism. Rochester,VT: Inner Traditions, 1999.

-

Uehli, Ernst. Atlantis und das Rätsel der Eiszeitkunst. Stuttgart, Germany: J. Ch. Mellinger Verlag, 1980.

FIGURE CAPTIONSFigure 1. A Lapp shaman's drum, from early nineteenth-century northern Sweden, illustrates the three worldsto which the shaman has access.

Van James is an artist and writer living in Honolulu, Hawai'i. He is editor of Pacifica Journal and author of three guide books on ancient Hawaiian sites. His most recent book Spirit and Art: Pictures of the Transformation of Consciousness (Anthroposophic Press 2001) was reviewed in the March/April 2003 issue of Quest.