The Twisted History of the Swastika

Printed in the Winter 2016 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Smoley, Richard. "The Twisted History of the Swastika" Quest 104.1 (Winter 2016): pg. 22-23

By Richard Smoley

If you were asked to come up with a symbol for evil, very likely you would think of the swastika. The quintessential emblem of the Third Reich, it still evokes hatred and fear seventy years after the collapse of the Nazi regime.

If you were asked to come up with a symbol for evil, very likely you would think of the swastika. The quintessential emblem of the Third Reich, it still evokes hatred and fear seventy years after the collapse of the Nazi regime.

And yet not so long ago it was a symbol of blessings and good fortune. Even its name is derived from Sanskrit roots meaning “it is good.” (Other names given to it include the cross patteé, the gammadion, the hakenkreuz or hooked cross, and the fylfot.) Today, in a somewhat truncated form, it still occupies a place in the official symbol of the Theosophical Society.

The peculiar fate of the swastika has a great deal to teach about the nature and meaning of symbols — and about the uses to which they can be put.

The swastika occurs almost universally. The most ancient version known is on a carved tusk from the Ukraine, dated to around 10,000 BC. Other early instances were found at Hissarlik in western Asia Minor, where Heinrich Schliemann, often called the father of archaeology, unearthed the ruins of Troy in 1873. The swastika begins to appear in the city’s third stratum, dated to 2250–2100 BC. It is on spindle-whorls, a sphere, and a statue made of lead thought to be an image of the goddess Artemis. The vulva (or perhaps the mons veneris) of this figure has a swastika in the middle. One scholar interpreted it as representing “the generative power of man” (Wilson, 811–13, 829).

Schliemann himself, following orientalist scholars of his time, said that the swastika was “of the very greatest importance among the early progenitors of the Aryan races in Bactria and in the villages of the Oxus, at a time when Germans, Indians, Pelasgians, Celts, Persians, Slavonians and Iranians still formed one nation and spoke one language” (Schliemann, 102).

But the swastika is found far beyond the traditional provenance of the “Aryan races.” Thomas Wilson, who wrote a study on it for the Smithsonian Institution in the late nineteenth century, lists examples from ancient sites ranging from Japan to Europe to North and South America. It’s quite apparent that the swastika belongs to everybody and to nobody.

Before we go into the swastika’s history, it might be best to clear up one source of confusion: its orientation. You will often hear it said that the “clockwise” direction of the swastika is the “good” direction, while the “counterclockwise” direction is the “bad” one.

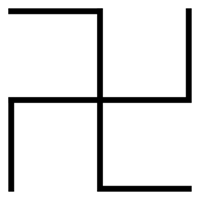

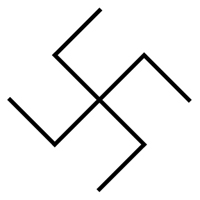

To begin with, consider these two images:

|

|

| Figure 1. Left-facing or "clockwise" swastika. |

|

|

|

|

| Figure 2. Right-facing or "counterclockwise" swastika. |

Which of these looks clockwise to you? To me, either one could be seen as clockwise, or counterclockwise, so I will avoid these terms. Instead I will speak of “left-facing” (for diagram 1) and “right-facing” (for diagram 2) swastikas. (If you’re curious, the left-facing one is most often described as clockwise.)

You can also forget about which direction is the good one or the bad one. Traditionally there seems to be no difference, and often both types appear in the same location — for example, on the curtain of a Tibetan temple devoted to the Bönpa, the nation’s pre-Buddhist shamanistic religion (Baumer, 21). Similarly Thomas Wilson, introduced to a member of a Chinese delegation visiting Washington, found him wearing robes of state emblazoned with both versions of the swastika. “The name given to the sign was . . . wan, and the signification was ‘longevity,’ ‘long life,’ ‘many years,’” Wilson writes. “Thus was shown that in far as well as near countries, in modern as well as ancient times, this sign stood for blessing, good wishes, and, by a slight extension, for good luck” (Wilson, 800).

So how did it come to stand for the complete opposite: hatred, violence, and cruelty?

Some historical background is needed. In 1871 Germany, which for centuries had been fragmented into dozens of tiny and often overrun states, was unified into a single empire, or Reich, by the Prussian chancellor Otto von Bismarck. Naturally Germans began to feel a thirst for a shared national identity. This began to form under a range of influences, from the treatise on Germany by the Roman historian Tacitus to the operas of Richard Wagner.

An identity is created out of many things, including the things you are against. Thus anti-Semitism soon became part of this German identity. Anti-Semitism had deep roots in Germany, going back at least as far back as Martin Luther, who in 1543 published a vituperative book entitled On the Jews and Their Lies. Wagner too was an anti-Semite.

Opposed to the Jews were, so the theory went, the Aryans. The word comes from the Sanskrit arya, meaning “noble,” and originally referred to the Indo-European peoples who conquered the Indian subcontinent in the second millennium BC. But soon it came to mean, above all else, the pure, white European race, which had reached the summit of perfection in the Germans.

What could serve as a symbol for this race? The cross was tainted by Christianity, which after all was founded by Jews. The fact that Schliemann had found the swastika in the ruins of Troy and Mycenae, the homes of an ancient, noble, and presumably Aryan race, spoke in its favor. It was (and is) found universally in India too, which had given the Aryans their name. And there was the verdict of the French symbologist the Count Goblet d’Alviella, who asserted that the swastika “is not met with in Egypt, Chaldea, or Assyria” — the last two being Semitic nations (Goblet d’Alviella, 40).

By the twentieth century, occult and pseudo-occult groups invoking the Aryan legacy were displaying the swastika. Hitler’s connection with these groups is suppositional at best, but it is fairly certain that he read and collected issues of the journal Ostara, founded in 1905 by the occultist Jörg Lanz von Liebenfels. The magazine’s subtitle — “Newsletter of the Blonds and Male Supremacists” — gives a good idea of its orientation. Its emblem was a knight in a hooded robe covered with swastikas.

Other extreme groups made use of the symbol as well, such as the Germanenorden, an occult lodge focused on ancient Germanic lore and of course anti-Semitism. Its founder was a self-styled aristocrat named Rudolf von Sebottendorff. As the German Reich collapsed in the fall of 1918, the order recast itself as the Thule Society (after Thule, a mythical polar land). Its symbol was a long dagger superimposed on a swastika sun wheel.

On November 9, 1918 — two days before Germany’s surrender in World War I — Sebottendorff delivered an impassioned speech to the Thule Society. Because of the imminent defeat, he declaimed, “in the place of our princes of Germanic blood rules our deadly enemy: Judah.” He urged his audience to fight “until the swastika rises victoriously out of the icy darkness” (Goodrick-Clarke, 144–45).

Direct connections between the Thule Society and the nascent Nazi movement are somewhat hard to trace, but there was at the very least an overlap of membership. In May 1919 a Thule member named Friedrich Krohn proposed the left-facing swastika as a symbol for the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (“German Workers’ Party,” or DAP), the precursor of the Nazi party.

Krohn evidently preferred this direction because he considered it auspicious, whereas, he said, the right-facing version portended disaster and death. But as Nicholas Goodrick-Clarke writes in his Occult Roots of Nazism, “there was no standard usage regarding the swastika” in this movement (or, as far as I can tell, anywhere else). The Germanenorden itself had used the right-facing version. Finally Hitler, who joined the party in November 1919 and soon rose to its leadership, chose the right-facing version, for reasons that are not clear (Goodrick-Clarke, 151).

But the meaning was clear. In his autobiography, Mein Kampf, Hitler writes: “The swastika signified the mission allotted to us — the struggle for the victory of Aryan mankind and at the same time the triumph of the ideal of creative work which is in itself and always will be anti-Semitic.” He credits himself with the design:

After innumerable trials I decided upon a final form — a flag of red material with a white disc bearing in its centre a black swastika. After many trials I obtained the correct proportions between the dimensions of the flag and of the white central disc, as well as that of the swastika . . . The new flag appeared in public in the midsummer of 1920. It suited our movement admirably, both being new and young. Not a soul had seen this flag before; its effect at that time was something akin to that of a blazing torch. (Hitler, chapter 7)

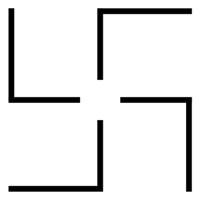

This, by the way, is the standard Nazi swastika:

|

| Figure 3. Nazi swastika. |

Notice one thing about this version. As figures 1 and 2 indicate, the traditional forms of the swastika appear in full vertical and horizontal orientation. But the Nazi swastika is decussated: it is cocked to a tilt of 45 degrees. This gives a greater impression of movement, possibly of a destructive kind. In this position it looks like a whirling blade. Hitler may have adopted it for this reason.

Nevertheless, the swastika did not have these meanings elsewhere in the world. In the U.S. it remained a good-luck sign, as evidenced by its use in the house organ of the Girls’ Club, called The Swastika. Up to the 1930s, the symbol appeared — with perfectly innocent intentions — on American goods ranging from poker chips and playing cards to the labels of fruit boxes. It was even the emblem of a lovable cartoon monkey named Bing-o. To this day in Asia it is still used, with auspicious connotations, on commercial signs and in religious ritual (Heller, 37, 90–101, 149).

But after Hitler came to power in 1933, the Western world came to link the swastika with hatred and violence. A synagogue in Hartford, Connecticut, had swastika patterns in its flooring, which the horrified congregation had to have paved over. When swastika flags were hoisted over three ocean liners docked in New York in 1935, a mob of 2000 people tore them down, provoking diplomatic protests from the Nazis. The swastika became so firmly equated with evil that it remains an emblem of fear for many — and for many others, it is still used for that purpose. The incarcerated cult murderer Charles Manson carved it into his forehead in 1970 (Heller, 13). It continues to surface among anti-Semites and fascists of various stripes. The present-day German republic forbids its public display.

All this gives a brief history of the use and abuse of the swastika in modern times. But what does the symbol really mean? This question is, I believe, not only difficult but unanswerable. But before I say why, let’s explore some of the meanings that have been ascribed to it.

One interpretation is given by Schliemann, citing a scholar named Émile Bournouf:

The

represents the two pieces of wood which were laid cross-wise upon one another before the sacrificial altars in order to produce the holy fire (Agni), and whose ends were bent round at right angles and fastened by means of four nails, so that this wooden scaffolding might not be moved. At the point where the two pieces of wood were joined, there was a small hole, in which a third piece of wood, in the form of a lance (called Pramantha) was rotated by means of a cord made of cow’s hair and hemp, till the fire was generated by friction. (Schliemann, 103–04; cf. Blavatsky, Collected Writings, 2:143–44)

The swastika is thus associated with fire — particularly the sacred fire known as agni, which is not to be confused with the physical manifestation per se. Because this fire is caused by friction, the swastika is also associated with motion. And from its shape, it is connected with the cross. Thus the swastika can represent a cross in motion. George S. Arundale, late president of the Theosophical Society, writes:

All that you feel in the sea you can feel infinitely more in the whirling of the Svastika [sic], for you yourselves are part and parcel of the whirling. The Svastika whirls because a God has set in motion the Wheel of the Law, and it is as if to its myriad spokes clung innumerable drops — the Men who are to become Gods. (Arundale, 225)

This passage is taken from Arundale’s Lotus Fire, a profound work that explores a sequence of symbols (the point, the web, the line, the circle, the cross, the swastika, and the lotus) that was, he claimed, “disclosed to me by a Lord of Yoga” (Arundale, 22). Arundale also observes:

I see . . . a very special appearance of relentlessness to the movement of the Svastika and to its effect upon the Men of the Sea [i.e., unindividuated beings] whom it frictions into ever-increasing Self-consciousness. The well-known phrase “broken on the wheel” — that horrible physical torture of earlier periods of history, perpetuated in modern days in terms of the mind, so that the inquisition of today is breaking its victims on the wheel of the mind, a terrible desecration of the Wheel of the Law . . . — occurs to me, for indeed is it ignorance which is broken upon the Wheel of the Love of God, the Wheel of His Salvation, the Svastika. (Arundale, 267–68; emphasis added)

H.P. Blavatsky, identifying the swastika with “Thor’s hammer” or “the hammer of creation,” says:

In the Macrocosmic work, the “Hammer of Creation,” with its four arms bent at right angles, refers to the continual motion and revolution of the invisible Kosmos of Forces. In that of the manifested Kosmos and our Earth, it points to the rotation in the circles of time of the world’s axes and their equatorial belts; the two lines forming the Svastika

meaning Spirit and Matter, the four hooks suggesting the motion in the revolving cycles. (Blavatsky, Secret Doctrine, 2:99; emphasis Blavatsky’s)

Other authorities have also linked the swastika to cosmic cycles. The French esotericist René Guénon writes:

The bent part of the arms of the swastika is considered . . . as representing the Great Bear seen in four different positions in the course of its revolution around the Pole Star, to which the centre of the four gammas are united naturally corresponds, and that these four positions are related to the cardinal symbol points and the four seasons. (Guénon, 85)

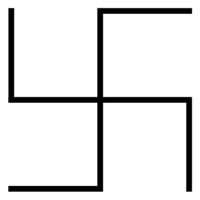

|

| Figure 4. The swastika seen as an arrangement of four Greek gammas. |

Guénon is talking about the fact that the four arms of the swastika resemble four gammas (the Greek capital gamma looks like this: Γ) positioned around a center point. He connects this fact with the symbolism of the letter G — the roman equivalent of the gamma — in Masonry. Hence also the name gammadion.

Furthermore, this center point would be the pole. (The point of view would be of someone looking down at the earth from above the North Pole.) For this reason, Guénon associates the swastika with Hyperborea, a prehistoric circumpolar civilization that was said to precede Atlantis. (Note: this is not to be confused with Blavatsky’s concept of the Hyperborean Root Race.)

So, then, the swastika is, or may be, connected with the four principal directions, portrayed symbolically as a cross. If so, then the decussated Nazi swastika would symbolize directions that are askew, and hence a world out of joint, possibly evil.

Incidentally one could say the same thing about the Soviet hammer and sickle. In essence it is nothing other than the cross (in this case, a T-cross) combined with the crescent — two of the most ancient and universal sacred symbols. But again its orientation is not rectilinear. Like the Nazi swastika, it is decussated — again suggesting something that is aberrant, out of joint, or evil.

Earlier I said that none of these associations, singly or as a whole, exhausts the meaning of the swastika. That’s because the swastika, like all other primordial symbols, has no ultimate meaning. It means itself. It speaks to a level of the mind that lies beyond the realm of meaning as we normally understand it. The same is true of other basic geometric shapes such as the six-pointed star and the crescent, the defining symbols of Judaism and Islam. These symbols will keep their living force for as long as the human mind is as it is. Meanings and movements will attach themselves to them and will try to draw power from them, often with success. Yet meanings come and go, while the symbol remains.

|

| Figure 5. The Soviet hammer and sickle. Conventionally it refers to the combined power of the workers (represented by the hammer) and the peasants (represented by the sickle. |

As theologian Paul Tillich writes, religious symbols open “the depth dimension of reality itself, the dimension of reality which is the ground of every other dimension and every depth . . . the fundamental level, the level below all other levels, the level of being itself . . . If a religious symbol has ceased to have this function, then it dies. And if new symbols are born, they are born out of a changed relationship to the ultimate ground of Being, i.e., to the Holy” (Tillich, 47, 49).

I believe that Tillich is right up to a point, but it is not so obvious to me that symbols — the primordial symbols, at any rate, of which the swastika is one — die. Or if they die, they are born again. Maybe it would be more accurate to say that they are recycled.

In recent years some have tried to cleanse the swastika of its evil connotations. In 1988–92 a Jewish artist named Edith Altman created an installation entitled Reclaiming the Symbol: The Art of Memory. In one scene, she has a gold swastika painted on a wall above a black Nazi swastika painted on the floor — a visual attempt to expunge evil from the symbol. In 2008, in a ham-handed effort to make the swastika humorous, cartoonist Sam Gross published We Have Ways of Making You Laugh: 120 Funny Swastika Cartoons. (Sample: a Nazi dropping garbage into a swastika-shaped bin labeled “White Trash Only.”)

But as graphic artist Steven Heller comments, “For every naïve rock-and-roller who thinks the swastika can be used with irony, there is a fervent neo-Nazi who uses it with malice. For every well-meaning artist who thinks the swastika can be tamed, there is a devout racist who embraces it” (Heller, 157).

In the long run, it’s likely that the swastika will be rehabilitated. Theosophist Arthur M. Coon observes:

The memory of the use of the swastika, as an emblem of Nazism will in future ages have faded to oblivion; while its true meaning as a symbol of the hidden “fire” or “spirit” within all manifestation, from the atom to a solar universe, will become increasingly revealed to humanity. (Coon, 120)

But I suspect that these future ages will not, at least in the West, come in the lifetime of anyone who is breathing on this planet now.

But I suspect that these future ages will not, at least in the West, come in the lifetime of anyone who is breathing on this planet now.

Sources

Arundale, George S. The Lotus Fire: A Study in Symbolic Yoga. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1939.

Baumer, Christoph. Tibet’s Ancient Religion: Bön. Translated by Michael Kohn. Trumbull, Conn.: Weatherhill, 2002.

Blavatsky, H.P. Collected Writings. 15 vols. Edited by Boris de Zirkoff. Wheaton: Theosophical Publishing House, 1966–91.

————. The Secret Doctrine. 2 vols. Wheaton: Quest, 1993.

Coon, Arthur M. The Theosophical Seal: A Study for the Student and the Non-Student. Adyar: Theosophical Publishing House, 1958.

“Edith Altman.” Center for Holocaust and Genocide Studies; http://chgs.umn.edu/museum/exhibitions/witnessLeg/survivorsRefs/altman/index.html; accessed Sept. 1, 2015.

Goblet d’Alviella, Count. The Migration of Symbols. London: Archibald Constable, 1894.

Goodrick-Clarke, Nicholas. Black Sun: Aryan Cults, Esoteric Nazism and the Politics of Identity. New York: New York University Press, 2002.

—–—–. The Occult Roots of Nazism: Secret Aryan Cults and Their Influence on Nazi Ideology. New York University Press, 1985.

Gross, Sam. We Have Ways of Making You Laugh: 120 Funny Swastika Cartoons. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2008.

Guénon, René. Fundamental Symbols: The Universal Language of Sacred Science. Translated by Alvin Moore, Jr. Cambridge: Quinta Essentia, 1995.

Heller, Steven. The Swastika: Symbol beyond Redemption? New York: Allworth, 2000.

Hitler, Adolf. Mein Kampf. Translated by James Murphy. http://www.greatwar.nl/books/meinkampf/meinkampf.pdf; accessed Aug. 27, 2015.

Jeffrey, Jason. “Hyperborea and the Quest for Mystical Enlightenment.” New Dawn (Jan.-Feb. 2000); http://www.newdawnmagazine.com/articles/hyperborea-the-quest-for-mystical-enlightenment; accessed Sept. 1, 2015.

Schliemann, Henry [Heinrich]. Troy and Its Remains: A Narrative of Researches and Discoveries Made on the Site of Ilium, and in the Trojan Plain. Edited by Philip Smith. London: John Murray, 1875.

“The Seal of the Theosophical Society.” The Seal of the Theosophical Society; accessed Aug. 28, 2015.

Tillich, Paul. The Essential Tillich. Edited by F. Forrester Church. New York: Macmillan, 1987.

Wilson, Thomas. The Swastika: The Earliest Known Symbol and Its Migrations, with Observations on the Migrations of Certain Industries in Prehistoric Times. Washington: Government Printing Office, 1896.

Richard Smoley’s latest book, The Deal: A Guide to Radical and Complete Forgiveness is available now. His next book, How God Became God: What Scholars Are Really Saying about God and the Bible, is due to be published by Tarcher/Penguin in June 2016.

It struck a chord with me because many times I’ve walked away from people, from situations, from relationships, and even from religions because they no longer fit or seemed right any longer. At these times I finally realize that the need to fulfill my own destiny (whatever that is), or to follow my path, steers me in another direction, because the direction I’ve been moving in no longer feels right. I have never been able to stay in one place very long — or with one person — and especially not with one religion. My Higher Self begins to stir something within me; my consciousness begins to shift, and I can feel myself beginning to pull away. It’s an odd feeling, even though I’ve felt it many times during my life. It is as if I am moving further from a particular situation or place in my life to make room for something else.

It struck a chord with me because many times I’ve walked away from people, from situations, from relationships, and even from religions because they no longer fit or seemed right any longer. At these times I finally realize that the need to fulfill my own destiny (whatever that is), or to follow my path, steers me in another direction, because the direction I’ve been moving in no longer feels right. I have never been able to stay in one place very long — or with one person — and especially not with one religion. My Higher Self begins to stir something within me; my consciousness begins to shift, and I can feel myself beginning to pull away. It’s an odd feeling, even though I’ve felt it many times during my life. It is as if I am moving further from a particular situation or place in my life to make room for something else. ser Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915) was a key figure in what is commonly called the Silver Age in Russian history (from the 1890s to the outbreak of World War I in 1914). This era saw a surge of interest in mysticism and in the occult and philosophical teachings of India and China, along with influences from Germany, including the thought of Nietzsche and the Christianized version of Theosophy developed by the Austrian visionary Rudolf Steiner. Rudolf Steiner’s second wife, Marie von Sivers, was a Baltic Russian. She helped spread Steiner’s views in Helsinki and Warsaw, cities in close contact with Russian intellectual circles.

ser Alexander Scriabin (1872–1915) was a key figure in what is commonly called the Silver Age in Russian history (from the 1890s to the outbreak of World War I in 1914). This era saw a surge of interest in mysticism and in the occult and philosophical teachings of India and China, along with influences from Germany, including the thought of Nietzsche and the Christianized version of Theosophy developed by the Austrian visionary Rudolf Steiner. Rudolf Steiner’s second wife, Marie von Sivers, was a Baltic Russian. She helped spread Steiner’s views in Helsinki and Warsaw, cities in close contact with Russian intellectual circles.

I was walking through “the yard” at San Quentin State Prison. The prisoners sunning themselves at tables near the worn baseball field would have pleased any casting director with their do-rags and the homemade prison tattoos on muscular bare arms. The man walking with me, though, was smallish, balding, middle-aged, and pale, making me think of an accountant. He might once have been an accountant, I don’t know; I do know he was a convicted murderer.

I was walking through “the yard” at San Quentin State Prison. The prisoners sunning themselves at tables near the worn baseball field would have pleased any casting director with their do-rags and the homemade prison tattoos on muscular bare arms. The man walking with me, though, was smallish, balding, middle-aged, and pale, making me think of an accountant. He might once have been an accountant, I don’t know; I do know he was a convicted murderer.