The Strange Identity of Jesus Christ

Printed in the Fall 2015 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Smoley, Richard."The Strange Identity of Jesus Christ" Quest 103.4 (Fall 2015): pg. 130-136.

Most Christians think the New Testament says that Jesus is God. They’re wrong.

By Richard Smoley

The New Testament may be the most widely read book in the world. And as everyone knows, the New Testament is about Jesus Christ.

The New Testament may be the most widely read book in the world. And as everyone knows, the New Testament is about Jesus Christ.

You would think, then, that people would know what the New Testament says about Jesus. But as it turns out, a great deal of what they know is wrong. Most people think it says he was God. Really? Then how do you explain verses like this, in which Jesus says, “Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is, God” (Matthew 19:17)? (Biblical quotations here and elsewhere are from the King James Version unless otherwise noted.)

Problems like this lead us to wonder exactly what the earliest Christians thought of Jesus.

In all likelihood they thought very different things. Even in the earliest generation of Christianity, there were many “faith communities,” often in the same vicinity, with different and competing beliefs. One extinct sect, a Jewish Christian group called the Ebionites, thought Jesus was a human like everybody else. Gnostic groups, by contrast, often saw him as a phantom materialized in this foul material world somewhat like a Tibetan tulpa. But none of them — at least none that we know of — thought he was God.

For this article, let’s focus on the Christians who wrote the New Testament, such as Paul, John the evangelist, and the unknown author of the Epistle to the Hebrews. Their writings all became validated as canonical scripture, so they must agree to a certain extent about who Jesus was. By and large they do. But weirdly, what they agree on is quite different from what the Catholic Church and its offshoots — which include practically the whole of the Christian world — later claimed.

To see why, let’s start with a much-discussed passage from Paul’s epistle to the Philippians, which says that Jesus, “being in the form of God, did not think that being equal with God was something to be grasped at, but he emptied himself, taking the form of a slave, being born in human likeness. And being found in human form, he humbled himself, being obedient unto death, death on a cross. Therefore God exalted him, and blessed his name above every other name” (Philippians 2:6–9; my translation and emphasis).

There is a lot about this passage that is obscure, and whole books have been written about it. For our purposes the main point is this: scholars believe that Paul did not write these words — not originally. Instead he is quoting a kind of doxology, or doctrinal formula, that is already familiar to the people he is writing to.

This is a curious fact, because Philippians was written sometime between AD 56 and 63. Meaning that by this time — no later than thirty years after Jesus’s death — he was widely venerated as a divine being by his followers.

But what kind of divine being? To say that Jesus “did not think that being equal with God was something to be grasped at” is peculiar. How could he “grasp at” being equal to God if, as most Christians today believe, he was God himself?

Here is another verse, again by Paul, in which he reminds the Galatians how well they treated him: “You received me as an angel, as Christ Jesus” (Galatians 4:14; my translation). The natural and obvious way of reading the Greek here is that “as Christ Jesus” is an expansion or elaboration of “as an angel.”

This suggests that the early Christians — and again, I’m referring to those who wrote the New Testament — did not think that Jesus was God. They thought he was the incarnation of an angel.

As New Testament scholar Bart D. Ehrman puts it: “Jesus was thought of as an angel, or an angel-like being, or even the Angel of the Lord — in any event, a superhuman divine being who existed before his birth and became human for the salvation of the human race. This, in a nutshell, is the incarnation Christology of several New Testament authors” (Ehrman, chapter 7).

We might also be able to say which angel they thought Jesus was. Quest readers may remember an earlier article of mine, “God and the Great Angel” (Quest, Winter 2011). In it I argue that, by some theories, there were originally two Gods in Israel: El, the high God, and Yahweh, God of Israel alone, sometimes known as the Angel of the Lord. Eventually, however, the Jews decided that Yahweh was not an angel; he was the high God himself; El and Yahweh were the same. This transition had probably been made by the sixth century BC.

But the Great Angel did not go away. He continued to survive in Judaism for centuries afterward. He was sometimes known as the Son of Man.

The first usage of “the Son of Man” in this sense appears in the book of Daniel, from the second century BC: “I saw in the night visions, and, behold, one like the Son of man came with the clouds of heaven, and came to the Ancient of days, and they brought him near before him” (Daniel 7:13).

Sometimes the Son of Man was called Metatron, a name that looks more Greek than Hebrew. That may be because it is. One theory (there are many) says this name comes from the Greek metà toû thrónou — the angel “with the throne” of God.

Metatron, the Great Angel, was known in other ways too, depending upon which text you look at. Here is a list of some names for him:

The Angel of the Lord

The Son of Man

The Son of God

The second God (deúteros theós in Greek)

The Name of God

The Logos = The Word

Wisdom

It would take a long and highly technical treatise to go through all of these terms and explain where they occur and how they connect to each other. That’s impossible here. For our purposes it’s best to take them as a basket of names for more or less the same concept. It would be hard to overstate the importance of this concept to early Christianity.

Here it is: there is a kind of subordinate God, a “second God,” through whom the high God relates to the universe and through whom he created the universe. This subordinate God is actually an angel — the Son of Man, Metatron.

One text that sheds some light on the subject is a pseudepigraphical work called 1 Enoch:

And at that time that the Son of Man was named, in the presence of the Lord of Spirits

And his name before the Head of Days.

And before the suns and the “signs” [i.e., constellations] were created

Before the stars of the heaven were made,

His name was named before the Lord of spirits.

(1 Enoch 48:2–3; Idel, 20)

Exactly as in the verse from Daniel, there are two figures here: one is the Lord of Spirits, the Head of Days (or Ancient of Days), the high God, the Father. The other is the Son of Man. You will notice that the last line of the verse above emphasizes his “name.” This is important.

The ancient Hebrews saw a much closer connection between the word and the thing than we do. In fact, they used the same word for both: davar. This fact meant that God’s name was, in some way, equivalent to God himself. (To this day pious Jews sometimes refer to God as ha-Shem, “the Name.”)

The Name is a hypostasis. It is an attribute (usually of God) that takes on a life of its own and becomes a kind of independent entity, a person.

It’s even in the Bible. In Exodus the Lord says to the children of Israel, “Behold, I send an Angel before thee, to keep thee in the way, and to bring thee into the place which I have prepared. Beware of him, and obey his voice, and provoke him not: for he will not pardon your transgressions: for my name is in him” (Exodus 23:20–21; my emphasis).

So the Son of Man is the Great Angel, the hypostasis of the Name. Why was he called the Son of Man? Here’s one answer: many of these texts are not just the results of imagination or theologizing. They sometimes represent real visionary experience. We have almost no idea of how this kind of experience was produced. But in it the angels often had the form of men.

The texts say this over and over. Here’s a well-known example, from the famous throne vision of Ezekiel: “And above the firmament . . . was the likeness of a throne, as was the appearance of a sapphire stone: and upon the likeness of the throne was the likeness of the appearance of a man above upon it” (Ezekiel 1:26).

But there’s more. Metatron may have been called the “Son of Man” because he originally was (or was believed to be) a man. Enoch, to be specific. Antediluvian patriarch, great-grandfather of Noah, after living 365 years, “Enoch walked with God: and he was not; for God took him” (Genesis 5:24).

That is all the Bible has to say about Enoch.

But Jewish mysticism had much more to say. Enoch was not only taken to heaven, but was elevated to the highest of all positions. In fact he became Metatron, the Great Angel.

Below is a verse from a mystical text known as 3 Enoch, which tells of a rabbi’s journey into the heavenly realms. In it Metatron says:

I am Enoch, the son of Jared. When the generation of the Flood sinned and turned to evil deeds, . . . the Holy One, blessed be He, took me from their midst to be a witness against them in the heavenly height. (3 Enoch 4:1; in Charlesworth, 1:238)

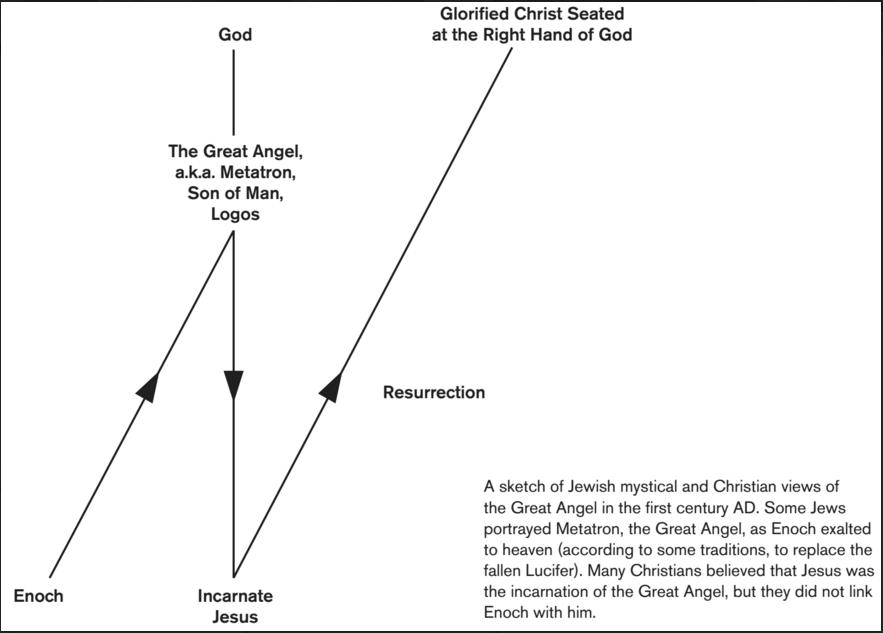

To sum all of this up: Judaism at the time of Christ, and long before, had a notion of the Great Angel, the hypostasis of the divine Name. At some point he was identified with the patriarch Enoch, who had ascended to heaven and become the angel Metatron. This may be why Metatron was called the Son of Man.

Christianity took this idea over. The early Christians decided that Jesus was the Son of Man, the Great Angel, who had come down to earth. He had degraded himself to take on fleshly form in order to deliver us from our sins. God rewarded him by exalting him to a still higher level than he had had before.

This is what the passage above from Philippians is trying to say. Here is another example, from the epistle of the Hebrews:

God, who at sundry times and in divers manners spake in time past unto the fathers by the prophets, hath in these last days spoken to us by his Son, whom he hath appointed heir to all things, by whom also he made the worlds: who being the brightness of his glory, and the express image of his person, and upholding all things by the word of power, when he had by himself purged our sins, sat down on the right hand of the Majesty on high: being made so much better than the angels, as he hath [been allotted] a more excellent name than they. (Hebrews 1:1–4; my emphasis)

The bracketed passage indicates my own addition to the King James translation. That’s because the King James Version fails to translate one word in the Greek: keklÄ“ronómÄ“ken, “has been allotted.” To say that Jesus was “allotted” his excellent name created some discomfort in light of later belief, so the word was left out. Most translations, even the most reputable and up-to-date ones, do similar things with passages like these.

The Great Angel starts with a very high status. He is right below God himself. In fact, God made the creation through him. But the Great Angel chose to come down to earth, become human, and offer himself up for our sins, so God elevated him to a still higher standing, to God’s right hand. He is thus no longer below God, but is literally on the same level.

The verses from Hebrews also say that God made the worlds through the Great Angel. You may be reminded of the opening of the Gospel of John: “All things were made by him” — the Logos, the Word (John 1:3).

You’ll also have noticed that I put the Logos, the Word, on the same list as the Great Angel and the Son of Man. That’s because the name Logos was also applied to the Great Angel. The first man to do this (to our knowledge) was the Jewish theologian Philo of Alexandria. Philo lived at the time of Jesus (Philo’s dates are c.15 BC–c.AD 50), although he never mentions Jesus and apparently doesn’t know of him.

But Philo does know of the Logos:

And even if there be not as yet any one who is worthy to be called a son of God, nevertheless let him labour earnestly to be adorned according to his first-born word, the eldest of his angels, as the great archangel of many names; for he is called, the authority, and the name of God, and the Word, and man according to God’s image, and he who sees Israel. (Philo, On the Confusion of Tongues, 146; Yonge, 247; my emphasis)

There you have it. The “great archangel” is “the name of God” and “the Word.”

“Word” here is a translation of the Greek lógos. Lógos is an extremely common word in Greek. And it does mean “word.”

Sort of.

In fact when I think back to any Greek text I’ve read, “word” is almost never the best translation for lógos. It’s often best translated as “speech,” “argument,” “reason,” even “true story.” But its meaning goes far further still.

It’s no small feat to say what lógos meant over the course of a thousand years of ancient Greek philosophy. But here is the main idea: lógos is the structuring principle of consciousness. Or, if you like, consciousness as a structuring principle (Heidegger, chapter 2; Smoley, 165).

What on earth do I mean by this?

To understand, simply take a look at your surroundings. Whether they’re familiar or not, you can easily identify objects and people: a table, a chair, that man over there, and so on. Your mind is picking them out from a background of colors, sounds, and other impressions. By picking them out, your mind is organizing them. They are no longer an ocean of random sense data. They are an organized and coherent world. Moment by moment, the lógos in you is creating the world.

It’s no coincidence that the root behind lógos is the verb légÅ, which originally meant “to pick up” or “pick out.”

By the time of Philo, Greek philosophers had devoted a lot of attention to this idea. In his day, the Stoics were one of the dominant philosophical schools. They said that this lógos, this structuring principle of consciousness, was the basis not only of our experience but of all existence. This idea was extremely influential.

Philo wanted to connect traditional Jewish teachings with Greek philosophy. So he identified this lógos with the Name, the Great Angel.

One man who was probably familiar with Philo’s thought — or with a system very much like it — was the evangelist John. That was how he came to write “In the beginning was the lógos, and the lógos was with God, and the lógos was God” (John 1:1).

Philo identified the Logos with the Great Angel. We see in Philippians that the Great Angel was identified with Jesus. John the evangelist made the obvious connection. The Logos=the Great Angel, incarnated in Jesus.

If this Great Angel was so important, you may be asking why you haven’t heard of him before.

Here’s one reason. At one point the Jewish sages decided that he had gotten too big for his britches. So they dethroned him.

We find out about this in 3 Enoch. It is a striking and revealing passage.

At one point a heretical rabbi ascends to heaven in a mystical vision. He sees Metatron on his throne and exclaims, “There are indeed two powers of heaven!” Then God dethrones Metatron. The angel Anapiel comes and, Metatron says, “struck me with sixty lashes of fire and made me stand to my feet” (3 Enoch 16:2–5; Charlesworth 1:268).

The passage suggests why Metatron was dethroned. It refers to the rabbi as Acher (the “other one”) — a contemptuous epithet: the Jews considered him an archheretic. His real name was Elisha ben Abuya, and he lived around the turn of the second century AD. Although it’s not clear what kind of heretic he became, most likely he converted to Christianity.

If this is true, it tells us a great deal. The idea of “two powers of heaven” had been in Judaism for centuries. But the Christians used it to great effect: there was the Father, and there was the Son. They identified this Son with Jesus.

At some point the rabbis decided to rid themselves of this troublesome second god, who was leading mystics to heresy. Metatron was demoted in the heavenly hierarchy. He was, so to speak, taken off his throne and made to stand on his feet. Dethroning Metatron was a way of putting a distance between Judaism and Christian doctrines.

Nevertheless, Metatron is still mentioned in later Judaism, mostly in the Kabbalah, which preserves many of the most ancient and profound Jewish teachings. He is still identified with Enoch, who was, according to the Kabbalah, the first fully realized man.

The Great Angel vanished from Christianity because it continued to exalt the status of Jesus from the first to the fourth centuries. We’ve already seen how Jesus was placed on the right hand of God — made equal to God. The next step to say that not only was he equal to God, but that he had always been equal to God.

Thus the doctrine of the Trinity was born.

It was decreed as the official doctrine of the Catholic church at the council of Nicaea in 325. Those, including a bishop named Arius, who held that Jesus was originally a created being were expelled as heretics. Curiously, Arius’s views were probably closer to the beliefs of the New Testament authors than were those of the side that won.

Paul himself would have probably agreed more with Arius. It’s sobering to think that if Paul, the fount of all Christian theology, had been at the council of Nicaea, he would probably have been thrown out as a heretic too. But history is full of many such ironies.

I must add that the doctrine of the Trinity was not merely the fabrication of some fourth-century bishops. The sacred ternary is a universal motif. It is found almost everywhere, under different names. There is the Hindu trinity of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, as well as the three primordial elements, rajas (force), tamas (inertia), and sattva (equilibrium). Chinese philosophy calls this ternary “heaven,” “earth,” and “man.” Jewish mysticism uses the three letters in the name of Yahweh — yod (Y), heh (H) and waw (W) — to express the same idea. And the pagan Slavs had Tribog (“Three-God”), a three-headed deity. It would be an oversimplification to say that all these concepts are talking about exactly the same things. Nevertheless, the sacred ternary is a genuine, profound, and universal teaching. The Christian Trinity is merely one way of apprehending it. (See René Guénon’s Great Triad for a discussion of this matter.)

One question may arise: Clearly some of Jesus’s earliest followers saw him as the Great Angel, the Son of Man. But was that how he saw himself?

This is not a question that we can definitively answer with the information we now have.

Why? The oldest surviving Gospels are the four in the New Testament, and possibly the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas. But scholars almost universally agree that these Gospels do not exactly reflect what Jesus said or did. They include things that were attributed to him later that may have had little or nothing to do with what he said or taught.

This is the scholarly consensus. But it leaves us with a big question: how do you decide which things in these Gospels are authentic and which aren’t? There are many criteria, but all the theories at some point face the same impasse: if you decide to include or exclude a statement by Jesus, this must mean that you have some preconceived idea of who Jesus actually was. You are sculpting the evidence to fit this picture in your head.

If there were other sources about Jesus that were in the slightest bit reliable or informative, it would be different. But there are almost no references to him in surviving non-Christian literature of the first century.

So any statement about who Jesus thought he was has to be made extremely hesitantly and tentatively.

Take this verse, for example: “Foxes have holes, and birds of the air have nests; but the Son of man hath not where to lay his head” (Luke 9:58). Here Jesus is identifying himself with the Son of Man. But is this statement authentically by Jesus? It very much depends on whom you ask.

As a whole, scholars regard Jesus’s Son of Man statements as mostly authentic. This is partly because the later Christian church no longer remembered who the Son of Man was. (Present-day theologians often seem clueless about it as well.) For this reason, scholars tend to think that the idea of the Son of Man comes from the earliest years of Christianity, and probably to Christ himself. The later church was not likely to make up this title for him, because the church no longer knew what it meant.

Jesus, then, may have believed he was the incarnation of the Great Angel and hinted as much to his disciples. Did he also think he was the reincarnation of Enoch? That is a fascinating possibility that, to my knowledge, scholarship has not addressed.

He may also have thought he was the Messiah. This claim may be based in fact. In the Gospels, Jesus is identified with the Messiah as “the son of David.” That is, he was believed to be a descendant of the royal line of David. (Whether he really was in a biological sense is another question that can’t be answered.) Originally the Messiah — the “anointed one” — was used to refer to the kings of Israel and Judah. If Jesus was the descendant of David, then he was the rightful king of Israel — the anointed one, the Messiah.

But the role of this Messiah in the thought of Jesus’s time is far from clear. James H. Charlesworth, a professor at Princeton Theological Seminary, writes, “it is impossible to derive a systematic description of the functions of the Messiah from the extant references to him” in the literature of Jesus’s time, because there actually aren’t many references to the Messiah in that literature (Charlesworth, 1:xxxi).

By all the evidence, if Jesus believed he was the Messiah, he saw his role in a spiritual sense; he was not interested in the political liberation of the Jews. But the priests were able to use the political implications of this title to frame him as an agitator and hang him by it. This explains the whole background of the Passion narrative.

If what I am saying above is true, it has enormous repercussions. There are hundreds of millions of people walking around today who believe that unless you accept Jesus as God, you are headed straight for eternal damnation. Most of these people also believe in the literal truth of the New Testament. What will they do when they learn that the New Testament itself doesn’t teach that Jesus is God?

This might be a liberating experience for some, but it’s just as likely to be a dispiriting and disorienting one. To have the bedrock of your faith crumble away under you is no small thing. It takes away the sole support that many people have.

This may be why most of the things in this article, while reflecting mainstream scholarship, remain virtually unknown. The clergy — at least in mainstream Protestantism and Catholicism — learned most of these things in seminary; it is not news to them. But they are reluctant or afraid to reveal them. Neither their education nor their denominations have prepared them to do so.

Eventually the truth will come out. What will happen when it does? I’m reminded of a passage in The Tree of Life Oracle, a fortune-telling deck based on the Kabbalistic Tree of Life by Quest contributor Cherry Gilchrist and Gila Zur. There is a card called “The Veil.” Here is the interpretation:

When the veil descended, men revered what it covered. And as time went on it seemed to hide more and more and was revered more and more. Then, when it was heavy with age, young men fresh and arrogant demanded the removal of the veil and demanded to see what was hidden. For they said that whatever is hidden from the people cannot be for the common good. In the thunder and lightning of indignation, the veil was torn down. Nothing lay beyond. At first the young men were startled, but then they laughed jubilantly at the absurd fraud they thought they had uncovered. And the old men grieved, cursing the young men because they had destroyed the veil. (Gilchrist and Zur, 108)

Sources

Charlesworth, James H., ed. The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha. 2 vols. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 2013 (1983).

Ehrman, Bart D. How Jesus Became God: The Exaltation of a Jewish Preacher from Galilee. San Francisco: Harper One, 2014.

Gilchrist, Cherry, and Gila Zur. The Tree of Life Oracle. New York: Friedman/Fairfax, 2002.

Guénon, René. The Great Triad. Translated by Peter Kingsley. Cambridge: Quinta Essentia, 1991.

Heidegger, Martin. Early Greek Thinking. Translated by David Farrell Krell and Frank Capuzzi. New York: Harper & Row, 1975.

Idel, Moshe. Ben: Sonship in Jewish Mysticism. London: Continuum, 2007.

Smoley, Richard. The Dice Game of Shiva: How Consciousness Creates the Universe. Novato, Calif.: New World Library, 2009.

Yonge, C.D., trans., The Works of Philo. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson, 1993.

This article is adapted from Richard Smoley’s forthcoming book, How God Became God: What Scholars Are Really Saying about God and the Bible, to be published in 2016 by Tarcher/Penguin.

We forget just how much the spiritual movements of the twentieth and now the twenty-first centuries owe to H.P. Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society she founded. Although not yet counted with Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud as a creator of our time, Mme. Blavatsky, no matter how wild her eccentricity or willful and capricious her natural freedom of spirit, deserves equivalent stature. Contemporary spiritual thinkers could not have accomplished what they have without her strenuous preparatory efforts. Much of what we think of as "New Age" — from Buddhism through "inner development" to channeling — was part of the original Theosophical mission.

We forget just how much the spiritual movements of the twentieth and now the twenty-first centuries owe to H.P. Blavatsky and the Theosophical Society she founded. Although not yet counted with Marx, Nietzsche, and Freud as a creator of our time, Mme. Blavatsky, no matter how wild her eccentricity or willful and capricious her natural freedom of spirit, deserves equivalent stature. Contemporary spiritual thinkers could not have accomplished what they have without her strenuous preparatory efforts. Much of what we think of as "New Age" — from Buddhism through "inner development" to channeling — was part of the original Theosophical mission. If one tries to understand Helena Petrovna Blavatsky's role in today's world, it is important to know how she is viewed in her native country — Russia. Hated, loved, highly revered by some and humiliated by others, she never found acceptance or support in her homeland. Her sister Vera wrote that HPB "was homesick to the last days, her heart was aching for the coming future of Russia."

If one tries to understand Helena Petrovna Blavatsky's role in today's world, it is important to know how she is viewed in her native country — Russia. Hated, loved, highly revered by some and humiliated by others, she never found acceptance or support in her homeland. Her sister Vera wrote that HPB "was homesick to the last days, her heart was aching for the coming future of Russia."