Remembering Krishnamrti: An Interview with Radha Burnier

Printed in the Spring 2015 issue of Quest magazine.

Citation: Krishna, P. "Remembering Krishnamrti: An Interview with Radha Burnier" Quest 103.2 (Spring 2015): pg. 50-55.

P. Krishna

Radha Burnier was the president of the international Theosophical Society from 1980 till her death in 2013. The daughter of N. Sri Ram, who was president of the international Theosophical Society from 1953 to 1973, she was an associate of the great spiritual teacher J. Krishnamurti (1895—1986; often called Krishnaji by his friends and admirers) and knew him from early childhood.

This interview with Mrs. Burnier was conducted by P. Krishna on July 21, 2001 in Krishnamurti's room at the Krishnamurti Study Centre at Rajghat, Varanasi, India. It has not previously been published.

This version has been edited for this issue. Professor Krishna includes the full version in his book, A Jewel on a Silver Platter: Remembering Krishnamurti, recently published by lulu.com.

P. Krishna: Radhaji, you knew Krishnaji very closely for a long time. I would like to begin by asking what your earliest memories of him are.

Radha Burnier: I was a very young child when he lived in the Theosophical Society at Adyar in the beautiful second-floor apartment which Annie Besant had got constructed for him. My brother and I used to frequently wander around there. I have vague mixed-up memories of Krishnaji walking there and playing tennis, of my brother and me going to his apartment and playing games with him, of his coming occasionally to our house for a meal. I was really too young then to have a chronological record of what all happened or give a detailed picture about it. But the curious thing is the feeling this contact created of exceptional joyousness, of meeting someone with a special atmosphere around him.

Krishna: When did you first meet him and have a talk with him and where?

Burnier: Around 1960-61, I do not remember the exact year; it was the early period of his Saanen [Switzerland] talks. I had gone there with a couple of my English friends and stayed in a chalet in Gstaad.

On one occasion, I had just left the tent and was walking along when Mme. Scaravelli's car passed by with Krishnaji in it. It passed by me and stopped after going some distance. They were looking back and calling me. I went up there, and Krishnaji said, "How is it you are here?" The way he said it, it sounded as if he knew who I was. I also felt he was not a stranger. He said, "We will meet, I will give you a ring." Later, when I had returned, I received a phone call and was invited to have lunch with him. I spent about one and a half hours with him, and we had lunch.

After that first meeting, whenever I went to Saanen, he would invite me for lunch, and my contact with him continued. I started going to other places to listen to him whenever I could. But my duties as general secretary [of the Indian Section] did not leave me with a lot of time to do so more often. I also continued to feel that just hearing him over and over again was not of much benefit, that one's ability to assimilate what he said was what mattered.

In a sense nobody could really know him. One could know things as memories and spend many days with him, as some people did, but the depth of his consciousness was such that one was not really knowing him. I think everybody knew him a little bit from different angles.

Krishna: Also, there seems to have been a great mystery about him which nobody really understands. In your interacting with him, did you have a feeling that he was like a great scholar or teacher, or was there something dimensionally different?

Burnier: I don't think he was a scholar at all. He frankly said he never read books, which was not strictly accurate, because he obviously had read some books. He certainly knew some of the beautiful phrases in the Bible.

But I have been told by trustworthy people who had clear memories of those days and knew Annie Besant well that [C.W.] Leadbeater made it a point not to inculcate anything into him, because they were so deeply convinced that a greater voice was going to speak through him that they did not want to force any ideas into his head.

There are people who say that Annie Besant said he was the Lord Maitreya and so on, but that is not correct. What Besant said was that the Maitreya consciousness would blend with that of Krishnaji, and his message and influence would pervade and go out to the world through him. So from the very early days, there was a great respect for this vehicle which was being prepared, and perhaps they did not feel that they should tell him what to think. On the other hand, they had to give opportunities for this boy to be prepared.

Krishna: Krishnaji advocates that we should observe each reaction and so on in the mirror of relationship and question it to learn about ourselves and come upon self-knowledge, which in turn brings wisdom, and that transformation comes from within. But if he did not go through this whole process, then how did he come upon all his wisdom?

Burnier: I think wisdom is in every consciousness in a germinal form. Otherwise, even for a man like Krishnaji, to talk to audiences would have no meaning. He himself has accepted that the door is open for every person to become free. He was not a freak. To be free inwardly is to open up the wellspring of wisdom, so I think in his case there was no barrier for this to happen. The outer mind being a pure mind, with almost no trace of selfishness ”which is what Leadbeater noticed when he first saw his aura" created no blockage, and the inner wisdom just came up when the time was ripe.

I remember once sitting outside in this very veranda, with Krishnaji and some others at the breakfast table. There was a talk about his not being interested in anything other than cars and clothes and so on in his boyhood. He said, "Yes, the time was not ripe for anything to well forth" from him. These words may not be exact. Then someone asked, "Who decided when the time was ripe?" He said, "The powers that be."

He was again asked, "Who are the powers that be?" He would not answer that question and just waved his hand. To me it seems he was obviously referring to what he sometimes called the powers of goodness. There are energies at subtler levels, in dimensions of which we have very little or no concept, which are perhaps watching over the world.

You cannot explain the source of things. In the last few years of his life he kept asking, "What is the source of life?" There is a dimension from which something comes down here.

Krishna: So when the Theosophists talked about the Masters, were they supposed to be personifications of this larger intelligence?

Burnier: First of all I must object to this kind of description, which is so much favored by people in the Krishnamurti Foundation. The phrase "what the Theosophists say" has no meaning whatsoever. The Theosophical Society admits almost anybody who accepts the value of the universal brotherhood of humanity. The Theosophical Society has officially said years ago that there is no authority in the Society, not even Mme. Blavatsky. Every person, through his own reflection, purity of life, enquiry, has to discover the truth within. So there are all kinds of people in the Society, with very different opinions and many approaches to the question of wisdom. There is no one voice which you can say is the voice of the Theosophists. Therefore many different things have been said about the Masters.

Krishna: I understand that. But when people ask that question, they generally mean what some of the great Theosophists had to say about this matter.

Burnier: One of the prominent early Theosophists, A.P. Sinnett, received a number of letters from his Masters. They themselves said something about what the Masters are. One is that they are completely unselfish. The qualification for becoming a Master is the daily conquest of the self. In other words, to give up completely the idea of a separate self. In another letter, they say only your evolving spirituality can bring you near to them.

Among the prominent Theosophists, I think this idea was the strongest: that the unfoldment of a human consciousness does not stop with humanity at its present stage. There is much more to which the consciousness can awaken. One of the Masters, in the letters which I just mentioned, says that there is a latent meaning and a hidden purpose in every individual existence, not just human existence. The whole universe is happy, and you wake up to that when the mind gets cleansed of all selfishness, any desire for oneself.

This purification of the self means the practice of what Krishnaji would later have called "attention," which, in the first little book he wrote, At the Feet of the Master, is called "discrimination." It means you are constantly giving attention to what is real and not real, what is important and what is not important, what is essential in life and what is inessential.

That is an important qualification: not to be attached, not to have desire. Not to be possessive is another qualification. So if that kind of quality develops in the consciousness and it becomes capable of embracing all in compassion and love, then that is the state of the Master. The Master is not a physical body, it is a state of consciousness, and that consciousness is everywhere.

Krishna: Would you say that Krishnaji was an individual in contact with the Masters, or would you say he was a Master?

|

|||

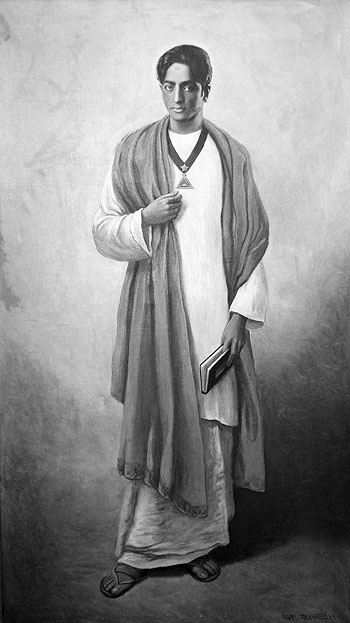

| Radha Burnier, portrait by Ruben Cabigting, 2012. From the collection of the Theosophical Society in America. |

Burnier: Both. There was a conversation around 1975 in which Krishnaji himself asked the question, "What is a Master?" I said, "You yourself speak about the possibility of the inner freedom of the human being. From the Theosophical point of view the Master is someone who has come to that state of inner freedom, but out of compassion remains in contact with ignorant humanity, to help them and to teach them, like the bodhisattva. Not all liberated, enlightened people, it is said, take up this work. They may be doing some cosmic work, we don't know. But some of them remain in touch with the earth, and they are called the Masters; others are called the liberated ones, the perfect ones, whatever it is. So the Master is someone who has come to this state of freedom and who teaches people," and I added, "Sir, I believe you are a Master."

That put an end to the whole conversation. There was a period of silence, and then he turned to something else. But I do think that he was in touch with other people, perhaps they were his teachers, perhaps there is, as Edwin Arnold said in The Light of Asia, veil after veil that lifts. Even when there is an awakening, there may be depths, unknown depths, about which we don't know.

Just before Krishnaji died, he said, "I am ready to go, they are waiting for me, but the body has its own program." Who were the "they" waiting for him? I think he was in touch with people who were at that level of consciousness.

On one occasion he said to me also that the mistake that the Theosophists did was to make the Masters into something personal and concrete. They are not that.

Of course, there are lot of people in the Theosophical Society who converted this truth about the Masters into many different things according to their liking.

Krishna: Why did Krishnaji have to leave the Theosophical Society, and how does his message really differ from that of Theosophy?

Burnier: I think he left the TS because there was a lot of folly in the TS at that time. There were many people who imagined, maybe even a few who pretended, that they were in touch with the Masters; they were bringing messages from them; they claimed certain occult positions for themselves, and things like that. Also, instead of regarding Theosophy as the essence of wisdom, they were presenting Theosophy as a set of crystallized beliefs or ideas. Krishnaji rebelled strongly against that.

But I am also wondering whether "the powers that be" intended that he should not be associated or identified with any organization. I think the work was on such a large scale that being part of an organization may have hampered it.

It was Annie Besant who really prepared the ground. When he broke off, he had friends all over the world to organize his talks, etc. In fact she encouraged people to work for him. If she had not done that, he would have been left high and dry.

There was a very deep feeling of love which bound them together. But in Mrs. Besant's last years, I am told, based on some comments by Krishnaji made to my father and others, when her body had somewhat broken down with too much work, her mental powers were not at the same level. She became much more subject to the influence of some people who were close to her, and perhaps at that age her real self was not able to function through her. So it was a shock to her when Krishnaji left, and there was all this commotion of breaking up. If you study her previous life, she never hesitated to break away with something and go along new lines.

Once I asked Krishnaji a question which many people have asked him: "You have been talking for so many years and nobody seems to have undergone this total revolution. Is there anybody you feel who was near it or something like that?" He said, "I think if Amma had been younger, it would have taken place in her." He referred to Annie Besant as Amma.

Krishna: So would it be correct to say that Krishnaji was not against Theosophy, as is commonly maintained by many people, but he was against all crystallized forms of beliefs and speculative theories wherever they were given too much emphasis, whether in the Theosophical Society or outside?

Burnier: And creating authority. If you create an authority in an organization, it becomes corrupt. He was against all that, and the Theosophical Society was in danger of going in that direction at that time.

"Theosophy" is a word which can be interpreted, like the word "Masters," in all sorts of ways, and people did interpret it in many ways. But I think he had a deep feeling for the Theosophical Society. I have been told that somebody had once spoken in a derogatory way about Dr. Besant, Leadbeater, and some of these people in a dialogue. Krishnaji corrected him saying, "You know, they were very serious people." So I think his view is not something which is easy to grasp.

And he contradicted himself. When he looked at certain wrong things, he would make certain kinds of remarks, and at other times he would make other remarks. Once he asked me, "What is going on in the TS? What were the subjects in the convention? Who is going to succeed your father as president?" These questions were repeated every year, but that year I picked up courage and said, "Sir, why do you ask all these things? I thought you had written off the TS." And he answered, saying, "You know, I have a great affection for it."

The fundamental work of the Society"”it is a declared object"”is to establish a nucleus of the universal brotherhood of humanity irrespective of religion, caste, color, etc. Now how can that kind of universal brotherhood come about unless the mind is free of all prejudices and barriers? If the mind is free like that, is it very different from the unconditioned mind that Krishnaji spoke of?

Krishna: I think Krishnaji is saying you have to realize the truth that the other human being is your brother, or yourself, and not merely have a belief that he is your brother.

Burnier: Quite right. As a matter of fact one feels such a friendship not only with people but with every living thing, because we share the process of life, but the mind has to become unconditioned for that. He used the word "unconditioned," which of course suggests many things and gives a depth to the understanding of universal brotherhood, but I see no contradiction.

Krishna: Do you think Krishnaji was just a wise man who had come upon self-knowledge, or was he a divine being like an avatar?

Burnier: There is a very fine book, a set of lectures which Annie Besant gave, published under the title Avatars. The word "avatar" can refer to the descent of divine energies in different ways into our world. They spoke about the partial avatars and the complete avatars, or purna avataras. "Avatar" could mean those forces took actual embodiment and worked through that body and the consciousness which was functioning in that body; then that is a purna avatara. But it could also use someone who had all the right qualities and vibrations"”sensitivity, openness, etc."”to manifest itself. Again and again people have spoken about this vacant mind that Krishnaji talked about.

I am inclined to believe that here was an individual who had been prepared: Leadbeater said Krishnaji had had contact with Masters during many incarnations. Anyhow, he was completely unselfish. There was nothing he desired for himself. We all know that, those who have met him there was no ego sense, and this pure individual was there. He himself was a very advanced soul, if I might use the word "soul." But there seems to be something more, which poured in through him when he gave his public talks, sometimes even when he was explaining profound things in private discussions. There was some kind of an energy which flowed through him, and therefore I am inclined to believe that there were some greater forces which made use of this wonderful person to lift the world to higher levels.

Krishna: We know that he had powers to heal people, and I know at least ten people who were healed by him through these powers, though he told each one of them not to speak about it and he didn't want that known. Do you have firsthand experience of some such healing, and how does it take place?

Burnier: I have some firsthand experience of it. My brother, Vasant, had a lot of problems with his eye. There was retinal detachment. They treated him in a famous hospital in Bombay. He only got worse. He suffered very much. Casually on some occasion I said to Krishnaji, "I can't do such a thing, my brother is here and he has this problem." Krishnaji immediately said, "Bring him to me." I asked, "Would you mind, sir, if he meets you in my house?" He said, "Bring him there." So every evening he used to put his hands near the eyes of my brother, who was and still is a great skeptic. But he had to confess that the other eye, which was also in danger of becoming blind, had begun to steady itself. He said he was seeing light, though he was not seeing details. He admitted he was seeing light, even with the blind eye, and strangely, on the side where the better eye was, even his hair, which was completely grey, began turning a little dark! After that his eye never was in danger any more.

Krishna: Scientists would say that psychological healing is possible, but physical healing is a miracle; it can't take place like this. Whereas Krishnaji is saying the opposite. He is saying, "I can heal you physically of an ailment sometimes, but I can't transform your consciousness; you have to do it yourself."

Burnier: Absolutely. It is common sense, because at the physical or material level everything works mechanically. The cause and effect process is in operation, but at the level of the consciousness it doesn't work that way. So somebody else cannot do it for you.

|

||

| Portrait of J. Krishnamurti by Genry Schwartz of Oak Park, IL, 1926. From the collection of the Theosophical Society in America. |

Krihsna: Can anybody learn this, do you think, or does it require a superior being?

Burnier I don't think just anybody can learn it, because there is some kind of passivity which makes some people allow it to flow through, or they themselves have plenty of it, so there is no obstruction in their own bodies. It is very difficult to explain.

Krishna: The world was shocked to read Radha Sloss's biography of K. [Lives in the Shadow with J. Krishnamurti] and learn that he had a sexual affair with her mother [Rosalind Rajagopal]. Did it shock you to know that?

Burnier: I would not say it shocked me, but it took me by surprise. Simply because Krishnaji had said so many times in the presence of so many people, talking about the normal worldly living, "You people, you have gone through all this, but this person has never gone through all that." The impression produced by those words was completely contradicted by this fact.

In fact, I did not want to believe what was in the book, so I rang up Mary Lutyens, and she confirmed that it was a fact. But later on, the more I thought about it, the more I began to feel that his words were absolutely true, because when walking with him on the Adyar beach one evening, I asked him, "You have again and again said, you have never suffered, but this is not factual. Shiva Rao was with you in the cabin when the news of your brother's death came, and he has written that Krishnaji cried and cried for three days. You went through that sorrow of parting, but the fact is that by the time you landed after three days, everybody has said that you were completely at peace and radiant with happiness."

I said, "Sir, how I understand it is that the consciousness which went through that parting is not the consciousness which came out of that." He only said, "That is right." So that explains it. When he says, "I have never gone through this," I take it that this experience was also like that.

Krishna: Still, the question is, does a person who experiences abundant overflowing love ”as he seemed to” does he need to express it through sex?

Burnier: I think that there is much in the concept of karma. You create links with certain things, certain people, and those links bring you into contact with him or her. He must have had some karmic bonds with Rosalind.

So also [her husband D.] Rajagopal. He had the extraordinary privilege of being in intimate contact with Krishnaji for so many years. Something brought him near Krishnaji. It is not necessarily what people would normally call good fortune, but there are deeper connections.

I also sometimes speculated "it is nothing more than that” that when this enormous energy which he mentioned before he died went through the body, it must have caused great strain to that body. Was that why he had to relax with detective stories? Sometimes with stupid little jokes, looking at TV, with all the rubbish it showed? Similarly, people have even made sarcastic comments about women who were with him during the process. Perhaps he needed a gentle person near him who would be like a mother.

Krishna: In some religions, it is said that a truly holy man has no sexual feelings, as the male and female principles fuse within him. From this point of view, would you mean that he was not a truly religious man?

Burnier: I do not think that is correct, because sexual feeling is in the body. The body must feel it for the race to be perpetuated. Then in the human being it affects the mind. Desire arises. So it is only at that level of the conditioned mind and of the body. It has nothing to do with the real, pure consciousness, which is inside. So I think there is the possibility for a liberated soul, free of desire, personal desires and interests, to have any kind of relationship without being contaminated, because that mind is not at work. This is a purely physical thing. By eating, the person doesn't get contaminated, but if you are greedy for food, it makes a difference.

Krishna: Much of what Krishnaji has said is there also in the Hindu and Buddhist scriptures. What would you say is so special about his teachings?

Burnier: Well, first of all, all the scriptures are so mixed up that for the average person it is impossible to say what is true and what is not true there. And even for the nonaverage person, since the mind is conditioned, we can't say our idea that this is true is actually true. I think when the teachings come directly, as they did from Krishnaji, that kind of adulteration is not there.

The second thing is that he explained things which were put in epigrammatic terms by other people. Once Krishnaji asked a question which he asked many times, I don't know why: "Has anybody said this before?" I said to him, "Yes," and gave a concrete example.

In the Yogavashista, there is a verse which speaks about a mind which is completely in the present, which never wanders off to the past or to the future. The text says to live in the present is immortality. But it is one short verse. I don't think I would have understood anything of that if I had not heard Krishnaji. Maybe among the ancient teachers there were some who explained it, but it is all gone. Here was somebody authentic.

Krishnaji was speaking of the modern world, and he was giving something which would help humanity to emerge out of the disasters of the modern way of life. So I think the ancient teachings came in a new form, with all the power of personal knowledge.

P. KRISHNA is a Life Member of the TS and a trustee of the Krishnamurti Foundation India. His father was the younger brother of N. Sri Ram.

What is it about the normal course of living that evokes a sense of struggle? Whether we look to stories and aphorisms from the scriptures of the world, or to the teachings of the modern Theosophical movement, or simply to the common-sense phrases routinely uttered day after day, there is a shared recognition that in this world nothing comes easily.

What is it about the normal course of living that evokes a sense of struggle? Whether we look to stories and aphorisms from the scriptures of the world, or to the teachings of the modern Theosophical movement, or simply to the common-sense phrases routinely uttered day after day, there is a shared recognition that in this world nothing comes easily.